Experts say the computer virus found in a nuclear plant is the work of a foreign power

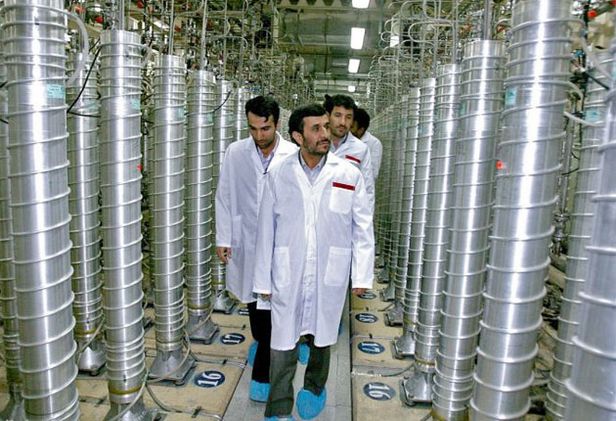

President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad visits one of Iran’s nuclear plants, which have come under attack from the virus

Computers can go wrong, and everyone is used to it. But that’s at home. We assume that the machines controlling the infrastructure that makes everything tick – power stations, chemical works, water purification plants – have rock-solid defences in place to deal with unexplained crashes or virus attacks by malicious strangers.

Now, though, a new kind of online sabotage has reached its zenith with a self-replicating “worm” that started on a single USB drive and has spread rapidly through industrial computer systems around the world.

So sophisticated that many analysts believe it can only be part of a state-sponsored attack, the Stuxnet worm – or “malware” – is the first such programming creation designed with the specific intention of causing real world damage. And if the experts are right, it could herald a new chapter in the history of cyber warfare.

The worm, designed to spy on and subsequently reprogramme industrial systems running a specific piece of industrial control software produced by German company Siemens, has now been detected on computers in Indonesia, India and Pakistan, but more significantly Iran; 60 per cent of current infections have taken place within the country, with some 30,000 internet-connected computers affected so far, including machines at the nuclear power plant in Bushehr, due to open in the next few weeks.

Yesterday Hamid Alipour, deputy head of Iran’s Information Technology Company, warned that nearly four months after it was identified, “new versions of the virus are spreading”. And he claimed that the hackers responsible must have been the result of “huge investment” by a group of hostile nations.

Despite intense scrutiny of the code by malware experts, they have so far been unable to discover exactly what the intended target of Stuxnet may be, or has been. But Alan Bentley, international vice president at security firm Lumension, is in no doubt that it’s “the most refined piece of malware ever discovered”.

The motive is certainly not, as is usual with such attacks, financial gain or simple tomfoolery; Stuxnet is intelligent enough to target specific kinds of industrial computer systems configured in a certain way and then, if it finds what it’s looking for, seek new orders to disrupt them.

Two potential targets of the worm may have been nuclear facilities within Iran at Bushehr and Natanz; indeed, a document on the website Wikileaks suggests that a nuclear accident may have occurred at Natanz during early July 2009, followed shortly afterwards by the unexplained resignation of the head of Iran’s Atomic Energy Organisation.

But if that was Stuxnet’s intended target, it has continued to spread regardless, causing consternation at industrial facilities worldwide. Melissa Hathaway, a former US national cybersecurity coordinator, has expressed particular concern at the availability of Stuxnet’s code and the techniques it employs to the wider internet community, saying: “We have about 90 days to fix this before some hacker begins using it.”

Security software firm Symantec has estimated that Stuxnet would have taken between five and ten specialists around six months to compile – a resource not within the means of the average internet criminal. One of the engineers working on unpicking the code expressed his surprise at the sophistication of the project, adding: “This is what nation states build if their only other option would be to go to war.”

Iran’s deeply controversial nuclear ambitions throw up any number of likely suspects, but a number of fingers have pointed at Israel, and in particular its intelligence corps, Unit 8200. Last summer, Reuters reported on Israel’s burgeoning cyber-warfare project, with a recently retired Israeli security cabinet member stating that Iran’s computer networks were very vulnerable.

Scott Borg, director of the US Cyber Consequences Unit, added that “a contaminated USB stick would be enough” to commandeer the controls of sensitive sites such as uranium enrichment plants – a rather prescient prediction.

The ramifications of this incident are considerable. Not only are there worries about the effects of Stuxnet, a largely invisible piece of malware, upon computers that are critical to people’s everyday lives, but there’s also great concern over the poor level of computer security being employed by those operating such machines. Stuxnet made its way into computer systems via vulnerabilities in Microsoft’s Windows operating system, before taking control of the Siemens software via its default password.

The fact that something as mundane as a password issue could have such a critical effect has also caused consternation amongst commentators and analysts – as has the unnerving announcement from Siemens to its customers not to change that password lest it “impact plant operations”. Siemens has offered a free download on its website to remove Stuxnet; while this is a common procedure for many viruses, it’s alarming that a nuclear facility would have to do such a thing to ensure its stability.

Stuxnet has kicked off an additional debate over exactly how prevalent this kind of cyber-attack may already be. This is far from the first incident where governments have found themselves under attack via computer.

Russian sites were attacked during the South Ossetia war in 2008. In 2007, the US suffered a vast data theft in what one senior official dubbed “an espionage Pearl Harbor”. And when Israel attacked a suspected Syrian reactor in the same year, it may have used an ” off switch” buried in the Syrian radar system to allow its aircraft to travel undetected.

And yet not every aspect of these attacks goes smoothly. For all the sophistication of the Stuxnet worm, one school of thought suggests that something actually went wrong; after setting itself a very particular task, it has accidentally spread to thousands of machines it never intended to attack, thus bringing it to wider attention and opening eyes to the possibility that this kind of activity may have been going on undetected for some time.

Iran’s official IRNA news agency reports that only personal machines have been affected at the Bushehr plant, with the main operating system unaffected. It is nonetheless safe to say that the new potential for industrial sabotage could soon make an old-fashioned error message seem like very small fry indeed.

By Rhodri Marsden

Tuesday, 28 September 2010

Source: The Independent