Related article:

Criminals!

A 2006 Immigration and Customs Enforcement investigation into the purchase of child pornography online turned up more than 250 civilian and military employees of the Defense Department — including some with the highest available security clearance — who used credit cards or PayPal to purchase images of children in sexual situations. But the Pentagon investigated only a handful of the cases, Defense Department records show.

The cases turned up during a 2006 ICE inquiry, called Project Flicker, which targeted overseas processing of child-porn payments. As part of the probe, ICE investigators gained access to the names and credit card information of more than 5,000 Americans who had subscribed to websites offering images of child pornography. Many of those individuals provided military email addresses or physical addresses with Army or fleet ZIP codes when they purchased the subscriptions.

In a related inquiry, the Pentagon’s Defense Criminal Investigative Service (DCIS) cross-checked the ICE list against military databases to come up with a list of Defense employees and contractors who appeared to be guilty of purchasing child pornography. The names included staffers for the secretary of defense, contractors for the ultra-secretive National Security Agency, and a program manager at the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. But the DCIS opened investigations into only 20 percent of the individuals identified, and succeeded in prosecuting just a handful.

The Boston Globe first reported the Pentagon’s role in Project Flicker in July, citing DCIS investigative reports (PDF) showing that at least 30 Defense Department employees were investigated.

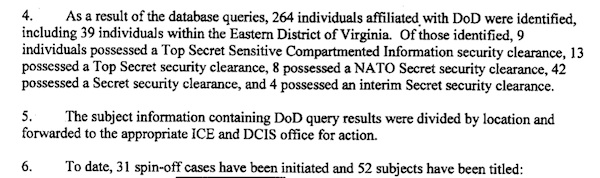

But new Project Flicker investigative reports obtained by The Upshot through the Freedom of Information Act, which you can read here, show that DCIS investigators identified 264 Defense employees or contractors who had purchased child pornography online. Astonishingly, nine of those had “Top Secret Sensitive Compartmentalized Information” security clearances, meaning they had access to the nation’s most sensitive secrets. All told, 76 of the individuals had Secret or higher clearances. But DCIS investigated only 52 of the suspects, and just 10 were ever charged with viewing or purchasing child pornography. Without greater public disclosure of how these cases wound down, it’s impossible to know how or whether any of the names listed in the Project Flicker papers came in for additional scrutiny. It’s conceivable that some of them were picked up by local law enforcement, but it seems likely that most of the people flagged by the investigation did not have their military careers disrupted in the context of the DCIS inquiry.

Among those charged were Gary Douglass Grant, a captain in the Army Reserves and a judge advocate general, or military prosecutor. After investigators executing a search warrant found child pornography on his computer, he pleaded guilty last year to state charges of possession of obscene matter of a minor in a sexual act in California. Others included contractors for the NSA with Top Secret clearances; one of them — a former contractor — fled the country after being indicted and is believed to be in Libya.

But the vast majority of those investigated, including an active-duty lieutenant colonel in the Army and an official in the office of the secretary of defense, were never charged. On top of that, 212 people on ICE’s list were never investigated at all.

According to the records, DCIS prioritized the investigations by focusing on people who had security clearances — since those who have a taste for child pornography can be vulnerable to blackmail and espionage. The documents show that the probe then concentrated on people who had been previously suspected of or convicted of sex crimes, or had access to children as part of their Defense Department duties. But at least some of the people on the Project Flicker list with security clearances were never pursued and could possibly remain on the job: DCIS only investigated 52 people, and 76 of those on the Project Flicker list had clearances.

A DCIS spokesman didn’t return phone calls. But the agency’s own documents obtained via The Upshot’s FOIA request indicate that the decision to press investigations forward hinged largely on questions of the resources available to the investigators. “Due to DCIS headquarters’ direction and other DCIS investigative priorities, this investigation is cancelled” is a common summation in the files.

A source familiar with the Project Flicker investigations — who requested anonymity because public disclosure could jeopardize this person’s job — confirmed that departmental resources, and priorities, were decisive factors in letting inquiries lapse.

DCIS is primarily tasked with rooting out contractor fraud and investigating security breaches; its 400 staffers were already plenty busy before Project Flicker dropped 264 more names onto their caseloads. And child pornography investigations are difficult to prosecute. Many judges wouldn’t issue search warrants based on years-old evidence saying the targets subscribed to a kiddie porn website once.

“We were stuck in a situation where we had some great information, but didn’t have the resources to run with it,” the source told The Upshot. Many of the investigative reports obtained by The Upshot end with a similar citation of scarce resources:

Of course, other federal agencies, including ICE and the FBI, may have prosecuted some of the Project Flicker names the DCIS ignored. But that’s unlikely, given that some of the DCIS investigations were closed due to lack of cooperation from ICE.

In one case, involving an Army Reserve corporal in the Pittsburgh area, a DCIS agent expressed exasperation after repeatedly trying to get ICE to collaborate with him on the investigation: “Based upon the complete non-responsiveness of ICE … it is recommended that [the] matter be closed.”

As for the 212 Project Flicker names that DCIS didn’t investigate, the source familiar with the investigation said there was no systematic effort to inform their superiors or commanding officers of their suspected purchases of child pornography.

By John Cook john Cook

Fri Sep 3, 10:30 am ET

Source: Yahoo News