Aid organisations are warning that millions of people are facing starvation from drought and crop failure in the West African country of Niger, and some people are turning to desperate measures to survive.

If you look up “bo” on the internet, nothing that makes sense comes up. But we were looking at a bo, or rather looking for it.

We were walking along the bank of the Niger river, searching for the tracks of a hippopotamus that was ravaging the corn on Karim’s farm.

All of a sudden, a lizard about the size of a small crocodile hurtled out of the undergrowth and raced up a nearby baobab tree.

“It’s a bo,” everybody cried, racing to the foot of the enormous tree.

Now I had never seen a bo before, so I was interested out of pure curiosity.

The handful of villagers with us had other ideas, though. “The bo is delicious,” explained Karim. “It has the taste and texture of fish, and the inside of it is all white.

“You don’t see them very often. There are not that many about.”

Moustafa, Karim’s head man, was talking excitedly into his mobile phone. “He’s calling the kids from the village,” explained our host.

“He wants them to climb the tree and get the poor creature down.”

It was hardly surprising, I thought, that the bo was scarce. It is rotten luck to be a delicious animal in a land where people are hungry.

Tortured beauty

For people are hungry in Niger. The rains failed last year and the staple diet of millet is running out.

There was famine in 1984, and again in 2005. Now it is about to happen once more.

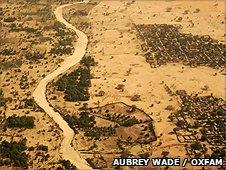

We travelled north to Tillaberi, a rolling landscape of sand, wind-blown dust, and sparsely scattered bushes and trees, seemingly in the very last stages of desiccation.

Here and there were thin cows, beautiful cows with tall horns, but with their hides hanging from fleshless frames.

The goats, too, the lovely black and white African goat, that looks as if it were jet black but had the front part of the body dyed white, have long ago given up hope of finding even the least scrap of sustenance from the parched earth.

As we travelled on, the country became even more barren, with here and there a dead cow, others on their last legs, moving like wraiths among the leafless trees.

This is not to say that the place was devoid of beauty. It possessed a tortured and hellish majesty.

At length we emerged from the nothingness we had passed through to a strange and unexpected scene: the wells of Timbouloulag.

Dotted amongst the sparse trees were a dozen low mounds. On the top of each was a hole, the edges of which were defined with twisted logs, set flush into the ground, like wooden lips.

Standing forlornly among the trees were scores of animals, patiently waiting to drink.

Hope among despair

In the shade of a particularly leafy tree sat a group of women, each enveloped in robes of beautifully printed cotton. Standing nearby, at one of the wells, was a corresponding group of men.

“Salaam alaikum.”

They smiled in welcome as we shook their hands.

They were a dozen or so, and they looked truly magnificent, tall and graceful with skin of flawless black, and swathed in robes of blue, black and white.

A proud-looking man stepped forward as spokesman.

He was Akili Mayaki, about 50 years old, and wearing a blue-and-white-striped djellaba and an immaculate white turban.

His people were destitute.

Many of their cattle, their sole source of support, were now too weak to stand. There was hope that this year the rains would not fail, and that somehow they would come through.

Hope there was too for the future, with improving education perhaps it would never get this bad again.

Finally, I asked him what I really wanted to know: how did he feel about this land he lived upon? Would he ever leave and go to the city in search of a less precarious existence?

Akili looked at me weighing his words, then he said: “When the rains come, and all these trees burst into leaf and flower, and the earth is deep in lush grass, then I tell you there is no more beautiful place on this earth.

“I would not leave here, not even to go to Paris.”

A villager in Timbouloulag prepares some leaves to eat

Tatola leaves are soaked and cooked for three hours before eating

Next, I turned to talk with the women. Who reclined, each with her baby, in the dappled shade.

They had a tin bowl full of what looked like dried bay leaves.

“These are the leaves of the Tatola tree,” said the young spokeswoman.

“We boil them and pound them and add a little salt, then we put them with the millet husks, which are all we have left now.

“The husks do not satisfy our hunger, but if we add some boiled leaves, it helps.”

Much later, far away back home in Spain I got an e-mail from Karim. The village kids were still camped beneath the baobab, waiting for the poor bo to come down.

By Chris Stewart

Niger

Page last updated at 11:38 GMT, Saturday, 26 June 2010 12:38 UK

Source: BBC News