The NSA has made extensive use of its text message database to extract information on people under no suspicion of illegal activity.

– NSA collects millions of text messages daily in ‘untargeted’ global sweep (Guardian, Jan 16, 2014):

• NSA extracts location, contacts and financial transactions

• ‘Dishfire’ program sweeps up ‘pretty much everything it can’

• GCHQ using database to search metadata from UK numbers

The National Security Agency has collected almost 200 million text messages a day from across the globe, using them to extract data including location, contact networks and credit card details, according to top-secret documents.

The untargeted collection and storage of SMS messages – including their contacts – is revealed in a joint investigation between the Guardian and the UK’s Channel 4 News based on material provided by NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden.

The documents also reveal the UK spy agency GCHQ has made use of the NSA database to search the metadata of “untargeted and unwarranted” communications belonging to people in the UK.

The NSA program, codenamed Dishfire, collects “pretty much everything it can”, according to GCHQ documents, rather than merely storing the communications of existing surveillance targets.

The NSA has made extensive use of its vast text message database to extract information on people’s travel plans, contact books, financial transactions and more – including of individuals under no suspicion of illegal activity.

An agency presentation from 2011 – subtitled “SMS Text Messages: A Goldmine to Exploit” – reveals the program collected an average of 194 million text messages a day in April of that year. In addition to storing the messages themselves, a further program known as “Prefer” conducted automated analysis on the untargeted communications.

An NSA presentation from 2011 on the agency’s Dishfire program to collect millions of text messages daily. Photograph: Guardian

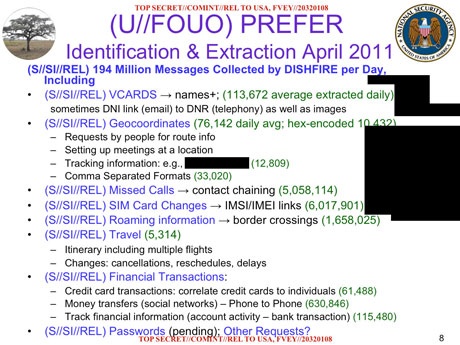

The Prefer program uses automated text messages such as missed call alerts or texts sent with international roaming charges to extract information, which the agency describes as “content-derived metadata”, and explains that “such gems are not in current metadata stores and would enhance current analytics”.

On average, each day the NSA was able to extract:

• More than 5 million missed-call alerts, for use in contact-chaining analysis (working out someone’s social network from who they contact and when)

• Details of 1.6 million border crossings a day, from network roaming alerts

• More than 110,000 names, from electronic business cards, which also included the ability to extract and save images.

• Over 800,000 financial transactions, either through text-to-text payments or linking credit cards to phone users

The agency was also able to extract geolocation data from more than 76,000 text messages a day, including from “requests by people for route info” and “setting up meetings”. Other travel information was obtained from itinerary texts sent by travel companies, even including cancellations and delays to travel plans.

A slide on the Dishfire program describes the ‘analytic gems’ of collected metadata. Photograph: Guardian

Communications from US phone numbers, the documents suggest, were removed (or “minimized”) from the database – but those of other countries, including the UK, were retained.

The revelation the NSA is collecting and extracting personal information from hundreds of millions of global text messages a day is likely to intensify international pressure on US president Barack Obama, who on Friday is set to give his response to the report of his NSA review panel.

While US attention has focused on whether the NSA’s controversial phone metadata program will be discontinued, the panel also suggested US spy agencies should pay more consideration to the privacy rights of foreigners, and reconsider spying efforts against allied heads of state and diplomats.

In a statement to the Guardian, a spokeswoman for the NSA said any implication that the agency’s collection was “arbitrary and unconstrained is false”. The agency’s capabilities were directed only against “valid foreign intelligence targets” and were subject to stringent legal safeguards, she said.

The ways in which the UK spy agency GCHQ has made use of the NSA Dishfire database also seems likely to raise questions on the scope of its powers.

While GCHQ is not allowed to search through the content of messages without a warrant – though the contents are stored rather than deleted or “minimized” from the database – the agency’s lawyers decided analysts were able to see who UK phone numbers had been texting, and search for them in the database.

The GCHQ memo sets out in clear terms what the agency’s access to Dishfire allows it to do, before handling how UK communications should be treated. The unique property of Dishfire, it states, is how much untargeted or unselected information it stores.

“In contrast to [most] GCHQ equivalents, DISHFIRE contains a large volume of unselected SMS traffic,” it states (emphasis original). “This makes it particularly useful for the development of new targets, since it is possible to examine the content of messages sent months or even years before the target was known to be of interest.”

It later explains in plain terms how useful this capability can be. Comparing Dishfire favourably to a GCHQ counterpart which only collects against phone numbers that have specifically been targeted, it states “Dishfire collects pretty much everything it can, so you can see SMS from a selector which is not targeted”.

The document also states the database allows for broad, bulk searches of keywords which could result in a high number of hits, rather than just narrow searches against particular phone numbers: “It is also possible to search against the content in bulk (e.g. for a name or home telephone number) if the target’s mobile phone number is not known.”

Analysts are warned to be careful when searching content for terms relating to UK citizens or people currently residing in the UK, as these searches could be successful but would not be legal without a warrant or similar targeting authority.

However, a note from GCHQ’s operational legalities team, dated May 2008, states agents can search Dishfire for “events” data relating to UK numbers – who is contacting who, and when.

“You may run a search of UK numbers in DISHFIRE in order to retrieve only events data,” the note states, before setting out how an analyst can prevent himself seeing the content of messages when he searches – by toggling a single setting on the search tool.

Once this is done, the document continues, “this will now enable you to run a search without displaying the content of the SMS, especially useful for untargeted and unwarranted UK numbers.”

A separate document gives a sense of how large-scale each Dishfire search can be, asking analysts to restrain their searches to no more than 1,800 phone numbers at a time.

An NSA slide on the ‘Prefer’ program reveals the program collected an average of 194 million text messages a day in April 2011. Photograph: Guardian

The note warns analysts they must be careful to make sure they use the form’s toggle before searching, as otherwise the database will return the content of the UK messages – which would, without a warrant, cause the analyst to “unlawfully be seeing the content of the SMS”.

The note also adds that the NSA automatically removes all “US-related SMS” from the database, so it is not available for searching.

A GCHQ spokesman refused to comment on any particular matters, but said all its intelligence activities were in compliance with UK law and oversight.

But Vodafone, one of the world’s largest mobile phone companies with operations in 25 countries including Britain, greeted the latest revelations with shock.

“It’s the first we’ve heard about it and naturally we’re shocked and surprised,” the group’s privacy officer and head of legal for privacy, security and content standards told Channel 4 News.

“What you’re describing sounds concerning to us because the regime that we are required to comply with is very clear and we will only disclose information to governments where we are legally compelled to do so, won’t go beyond the law and comply with due process.

“But what you’re describing is something that sounds as if that’s been circumvented. And for us as a business this is anathema because our whole business is founded on protecting privacy as a fundamental imperative.”

He said the company would be challenging the UK government over this. “From our perspective, the law is there to protect our customers and it doesn’t sound as if that is what is necessarily happening.”

The NSA’s access to, and storage of, the content of communications of UK citizens may also be contentious in the light of earlier Guardian revelations that the agency was drafting policies to facilitate spying on the citizens of its allies, including the UK and Australia, which would – if enacted – enable the agency to search its databases for UK citizens without informing GCHQ or UK politicians.

The documents seen by the Guardian were from an internal Wikipedia-style guide to the NSA program provided for GCHQ analysts, and noted the Dishfire program was “operational” at the time the site was accessed, in 2012.

The documents do not, however, state whether any rules were subsequently changed, or give estimates of how many UK text messages are collected or stored in the Dishfire system, or from where they are being intercepted.

In the statement, the NSA spokeswoman said: “As we have previously stated, the implication that NSA’s collection is arbitrary and unconstrained is false.

“NSA’s activities are focused and specifically deployed against – and only against – valid foreign intelligence targets in response to intelligence requirements.

“Dishfire is a system that processes and stores lawfully collected SMS data. Because some SMS data of US persons may at times be incidentally collected in NSA’s lawful foreign intelligence mission, privacy protections for US persons exist across the entire process concerning the use, handling, retention, and dissemination of SMS data in Dishfire.

“In addition, NSA actively works to remove extraneous data, to include that of innocent foreign citizens, as early as possible in the process.”

The agency draws a distinction between the bulk collection of communications and the use of that data to monitor or find specific targets.

A spokesman for GCHQ refused to respond to any specific queries regarding Dishfire, but said the agency complied with UK law and regulators.

“It is a longstanding policy that we do not comment on intelligence matters,” he said. “Furthermore, all of GCHQ’s work is carried out in accordance with a strict legal and policy framework which ensures that our activities are authorised, necessary and proportionate, and that there is rigorous oversight, including from the Secretary of State, the Interception and Intelligence Services Commissioners and the Parliamentary Intelligence and Security Committee.”

GCHQ also directed the Guardian towards a statement made to the House of Commons in June 2013 by foreign secretary William Hague, in response to revelations of the agency’s use of the Prism program.

“Any data obtained by us from the US involving UK nationals is subject to proper UK statutory controls and safeguards, including the relevant sections of the Intelligence Services Act, the Human Rights Act and the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act,” Hague told MPs.