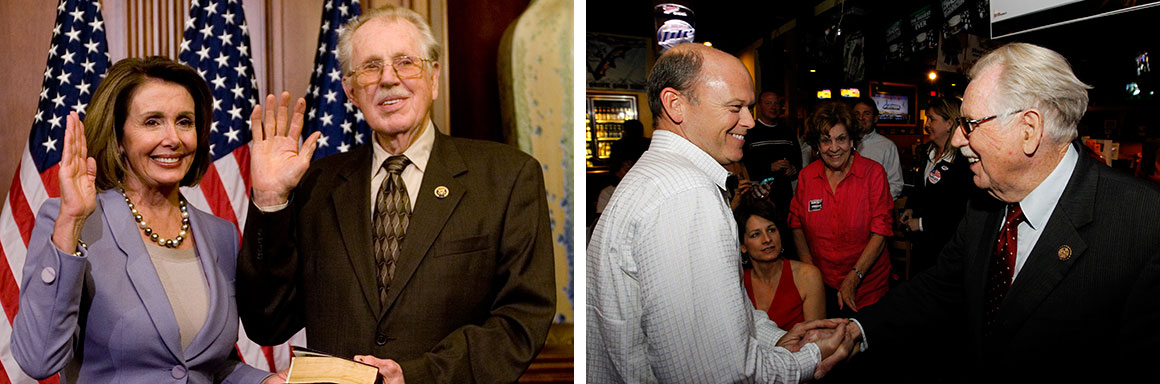

Bartlett, pictured with Nancy Pelosi in 2009, was by far the most conservative member of the Maryland delegation and was more than once called the “oddest congressman.” | AP Photo

– The Congressman Who Went Off the Grid (Politico, Jan 3, 2014):

When Roscoe Bartlett was in Congress, he latched onto a particularly apocalyptic issue, one almost no one else ever seemed to talk about: America’s dangerously vulnerable power grid. In speech after late-night speech on the House floor, Bartlett hectored the nearly empty chamber: If the United States doesn’t do something to protect the grid, and soon, a terrorist or an act of nature will put an end to life as we know it.

Bartlett loved to conjure doomsday visions: Think post-Sandy New York City without power—but spread over a much larger area for months at a time. He once recounted a conversation he claimed to have had with unnamed Russian officials about how they could take out the United States: They would “detonate a nuclear weapon high above your country,” he recalled them saying, “and shut down your power grid—and your communications—for six months or so.”

Bartlett never gained much traction with his scary talk of electromagnetic pulses and solar storms. More immediate concerns always seemed to preoccupy his colleagues, or perhaps Bartlett’s obsessions just sounded more like quackery than real science, even coming from a former Navy engineer who had worked on the space race. Whatever the reason, Congress’s failure to act is no longer Bartlett’s problem. The octogenarian Republican from western Maryland—more than once labeled “the oddest congressman”—found himself gerrymandered out of office a year ago and promptly decided to take action on the warnings others wouldn’t heed, retreating to a remote property in the mountains of West Virginia where he lives with no phone service, no connection to outside power and no municipal plumbing. Having failed to safeguard the power grid for the rest of the country, Bartlett has taken himself completely off the grid. He has finally done what he pleaded in vain for others to do: “to become,” as he put it in a 2009 documentary, “independent of the system.”

I visited Bartlett this past fall, following a set of maze-like directions—take a series of different forks in the road and look for the one paved driveway that turns off a narrow, rocky dirt road—as I climbed to nearly 4,000 feet, one of the highest U.S. elevations east of the Rocky Mountains. I lost cell phone service halfway into the four-hour drive from Washington and never got it back. The nearest shopping mall is more than an hour’s drive away.

When I arrived, Bartlett greeted me in faded denim overalls and an unruly white beard and asked if anything had happened since he was last in Maryland, about a week earlier. I told him that the National Security Agency had just been caught tapping into the connections between data centers run by Google and Yahoo. He looked nonplussed.

Limiting the role of government consumed much of his life for the 20 years he spent in Congress, leaving little time simply to sit by his lake and watch the sun go down and the bats come out. But nowadays, his concerns center around when the next frost will come and keeping mice out of the food pantries. He’s more interested in pointing out the different species of trees on his property or showing off his new composting toilet than discussing Obamacare (“just awful”) or the government shutdown (“lots of people realized we could get along just fine without the government”).

“You know,” he said after a pause, “the news now is like a soap opera. If you miss it for a week, you haven’t missed much.”

***

“People ask me ‘Why?’” Bartlett says as he is showing me around. “And I ask people why you climb Mount Everest. It’s a challenge, and it’s challenging to think what life would be like if there weren’t any grid and there weren’t any grocery stores. That’s what life was like for our forefathers.”

At 87, Bartlett hardly needs a reason to justify getting far away from the hustle and stress of Capitol Hill. There are no more votes to go back for, no more campaigning to do after nearly two decades as by far the most conservative member of Congress from the generally liberal state of Maryland. But he hasn’t fully withdrawn from society: Every couple weeks, he shaves, puts his suit back on and heads to Washington, where he serves as a senior consultant for Lineage Technologies, a cybersecurity group that seeks to protect supply chains. (“I don’t need to work, but I want to be responsible,” he says. “There are problems that need fixing, and I have some insight into these things.”)

Not that his life out here in the mountains is anyone’s idea of retirement. He rises at dawn every day except Saturday (he’s a Seventh Day Adventist) and spends 10 to 12 hours cutting logs, tending gardens and painting walls. I ask Bartlett, as he climbs a ladder to an attic, if he has ever had any health problems. No, he says, besides a little arthritis and acid reflux. He may be pushing 90, but his weathered skin, hearing aid and walking stick are the only reasons you’d think he’s gotten old. When his wife suggests we use “the Gator,” a John Deere golf cart-like vehicle, to tour their refuge, he refuses, preferring to go by foot.

Bartlett bought the 153-acre property in the early 1980s for $80,000 and built the five cabins himself, wiring the solar panels and running pipes from a freshwater spring to the cabins, work that consumed him on and off for the last couple decades. When he was a congressman, he would take his recesses and “working holidays” here, working on the cabins during the day and reading legislation at night. Now he’s midway through putting up a sixth house, a log cabin that will have a spacious kitchen, bathrooms with composting toilets, Internet access via satellite and a root cellar to store cabbage and potatoes through the winter. (Besides being more comfortable than his existing cabin, he needs the space to house his 10 adult children and their families, should his doomsday scenario come true.) The property also has a sawmill, a one-acre manmade lake with two pet swans, a gatehouse that arches over the long driveway and several gardens. It’s surrounded by mountains and wild apple trees and bears and tiny plants called club moss that look like pine trees if you get close. He’s got a mill for grinding flour, and on the day I visit his wife has whipped up potato onion soup made from produce grown in the garden and apple turnovers with apples that grow nearby.

It’s all part of practicing what you preach, he says. In Bartlett’s case, that’s a lifestyle that relies on the government and other people as little as possible. Certainly, that was always his political platform; as the congressman from Maryland’s 6th district, he advocated limited government, living within one’s means—and, more surprising perhaps for a conservative Republican, expanding green energy. In 2005, he founded the Peak Oil Caucus, a group concerned that the world will soon deplete its supply of oil. (“Roscoe was green before it was cool to be green,” Maryland Democratic Rep. Steny Hoyer once said.) He’s staunchly anti-abortion but searched for middle ground on stem cell research, and he’s a Second Amendment proponent who has never owned a gun. The Washington Postonce wrote that Bartlett had a “quirky, down-home conservative style,” and among his colleagues in Washington there was a clear sense that this was not just another cookie-cutter congressman: Bartlett, Rep. Howard “Buck” McKeon (R-Calif.) once said diplomatically, “comes at things from different angles.”

Bartlett was born in Kentucky in 1926. When he was an infant, his family moved to western Pennsylvania, where, he tells me, he “grew up dirt poor on a tenant farm.” It was there that he picked up most of the skills he has used to make life comfortable in his West Virginia retreat, and it’s also that upbringing that moved him to go into public service, after a science career that saw him go through IBM in its start-up years and the U.S. Navy as an engineer, before becoming director of the Space Life Sciences research group at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, where he helped the U.S. win the space race by, among other things, developing a device that allows astronauts to breathe at high altitudes and low temperatures.

“Growing up on a farm, you just learn to make do. You couldn’t possibly make enough money to hire an electrician or a plumber,” he says. “I went to the Navy, and they had some problems and I thought, ‘Gee, I can fix that.’ And I ended up getting 19 patents.”

I’ve long since forgotten Bartlett’s age and am just trying to keep up, having spent most of the day walking through dense forest, climbing ladders into crawlspaces and descending through trap doors into root cellars.

He worked his way through school, eventually earning a doctorate in physiology from the University of Maryland. In addition to working as an engineer, farmer and professor, he ran a consulting company and a construction business that built homes with solar power. While in Congress he reported a net worth of as much as $8 million. He got into politics at a time when, as he saw it, a rags-to-riches story like his own was becoming less possible.

“We were poor before the Depression, and we were poor after the Depression. But then I got a bachelor’s and a master’s and a doctorate,” he says. “I just thought that that kind of America I grew up in, where you could do that, wouldn’t be there for my kids.”

On the Hill, Bartlett voted against minimum wage increases, against bailing out the Postal Service and against expanding government in any meaningful way. He may have been green before it was cool, but he also was a Tea Party-style libertarian before there was a Tea Party. (During his last campaign he got into trouble for saying that federal student loans were unconstitutional and that ignoring the Constitution is a “slippery slope” that can lead to events like the Holocaust.)

So it’s no surprise that his decision on where to retreat from the world after Congress was all about escaping the heavy hand of government regulation.

“I wanted some privacy, and as far as I know, there are no inspections here for anything,” he says. “No permitting, no inspections. In Maryland, you pay taxes and think you own your land, but you really don’t. Some bureaucrats own it and tell you what you can do.”

Which is all to say, Bartlett doesn’t want the government to have more authority—with one notable exception.

***

During the four hours he spends showing me around, Bartlett continually stresses his reliance on only very basic technology to make his little corner of West Virginia livable—the solar panels and the batteries they charge, the power inverters, the water pipes and the wood stoves.

Bartlett tells me that the farm’s simplicity is a challenge, but it’s also an insurance policy. If he were to die, he says, his wife might not be able to repair more complicated technology. And besides, he tells me, if he used higher-tech power inverters “loaded with computers and chips and stuff,” they might fail, and then they’d be in trouble. I ask why that would be an issue—couldn’t they just drive to the nearest town to pick one up or order a new one off the Internet? “I have no idea,” he answers. “A giant solar storm? EMPs?”

EMP is shorthand for electromagnetic pulse, an electronic disturbance that can be delivered by a warhead—nuclear or otherwise—and that can instantly short out electrical equipment for as long as months at a time. For survivalists of Bartlett’s bent, it is one of the terrifying threats against which all this living off the land is designed to protect. As Bartlett points out to me, every single one of America’s 17 critical infrastructure systems—food and agriculture, water and sewer, transportation, emergency services and so on—are useless without electricity. Here in West Virginia, running a power system completely independent of the municipality, he’s safe in the event of a massive outage. (His wife also notes helpfully that at 4,000 feet, “an awful lot of the country could get flooded before it gets here.”)

And EMPs aren’t the only source of Bartlett’s concern. In 1859, the sun unleashed a flare—a powerful storm of energy—in the direction of the Earth. The charged particles from the storm lit telegraph wires on fire and put others out of commission for months. That storm is now known as the “Carrington Event,” after Dr. Joseph Carrington, the man who studied it. Such storms are estimated to occur once every 150 years—which means we’re overdue for another one. In the 1850s, we didn’t yet rely totally on electricity and technology, so the effects were minimal. A similar event today would cost between $600 billion and $2.6 trillion and could knock out the power grid between Washington and New York for up to two years, according to a June report by Lloyd’s, a British group that assesses risk for insurance companies.

In the last 36 months, there have been solar storms strong enough to disrupt GPS satellites, threaten the International Space Station and knock crucial military satellites offline for a few minutes. Stronger storms would damage or destroy electronics on Earth for an unknown period of time, and an EMP would have a similar effect. According to Bartlett, a terrorist with a “$100,000 Scud launcher and any crude nuclear weapon” could detonate a bomb above the atmosphere and knock out power for more than a year.

There are ways to “harden,” or protect, electrical transformers and other infrastructure, but doing so is costly. After a solar storm knocked out power in Quebec for 12 hours in 1989, the Canadian government invested $1.2 billion in hardening its grid, but no similar actions have been taken in the United States. The closest Congress has come was the GRID Act, a 2010 bill championed by Bartlett that would have ordered the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to explore ways to protect the electrical grid from cybersecurity and solar threats. The bill passed the House, but it was never taken up by the Senate—much to Bartlett’s frustration. “If an event is going to end life as you know it, how can you say it’s too expensive?” he asks. “It is an absolute certainty it’ll happen.”

Bartlett is still proud of one of his first cabins, an exercise in sustainability and heating efficiency. He has since learned not to put solar panels on the roof: “You can’t make adjustments when it’s up there. The sun is 93 million miles away, putting it on the ground, a couple feet further away doesn’t make a whole lot of difference,” he says. Bartlett has Internet access via satellite but still no phone service. For that, the family has to trek more than a mile up the road, to a specific spot they call “the phone booth” that they’ve discovered has cell service. | Photos by Jason Koebler

Bartlett isn’t the only one worried about EMPs: Newt Gingrich campaigned in the 2012 GOP presidential primary on the promise that he would protect the grid against an EMP attack, a possibility that Gingrich insisted would cause “millions [to] die in the first week alone.”

“You drove a long way to get here. How many houses did you see that were on fire?” he asks.

But Bartlett and Gingrich had few other allies in the government. Despite their pushing and prodding (Bartlett notes for me that a scientific commission he helped set up in 2004 concluded that “a determined adversary can achieve an EMP attack capability without having a high level of sophistication”), the alarm bells never really sounded in Washington. A common assessment, as Yousaf Butt, of the Federation of American Scientists, has put it, is that “if terrorists want to do something serious, they’ll use a weapon of mass destruction—not mass disruption.”

That’s why Bartlett stood essentially alone in pushing Congress to spend billions of dollars—even when he advocated budget cuts essentially everywhere else—to toughen up America’s power grid.

Bartlett calls it “the tyranny of the urgent.”

“That’s all I’m asking for,” Bartlett says. “A little common sense.” | Photo by Jason Koebler

“We’ve got to do something about it in Congress, but the urgent always takes priority over the important,” he tells me as we near the end of my tour. I’ve long since forgotten Bartlett’s age and am just trying to keep up, having spent most of the day walking through dense forest, climbing ladders into crawlspaces and descending through trap doors into root cellars. Before I leave, he asks me a question.

“You drove a long way to get here. How many houses did you see that were on fire?” he asks.

“None,” I say.

“Exactly, but I’ll bet you every one of them has fire insurance. And not one of them has insurance against something like this,” he says. “That’s all I’m asking for. A little common sense. This will happen, and we’re not ready for it.”

Well, maybe the rest of us aren’t. Roscoe Bartlett sure seems to be.

Our water supply was ‘contaminated’ with a bacteria recently, forcing everyone to boil their tap-water before drinking it.

It would not be unwise to consider the possibility our enemies could use municipal supplies to be accidentally polluted or infected.

http://prepforshtf.com/bottling-and-storing-your-own-water/