With Wall Street hemorrhaging jobs and assets, even many of the wealthiest players are retrenching. Others, like the Lehman Brothers bankers who borrowed against their millions in stock, have lost everything. Hedge-fund managers try to sell their luxury homes, while trophy wives are hocking their jewelry. The pain is being felt on St. Barth’s and at Sotheby’s, on benefit-gala committees and at the East Hampton Airport, as the world of the Big Rich collapses, its culture in shock and its values in question.

A snapshot: East Hampton, late summer, a lawn party at a house on the ocean overlooking the dunes. The host is a prince of private equity known for dressing well. One of his guests is Steven Cohen, the publicity-shy billionaire whose SAC Capital, with $16 billion under management, is perhaps the most revered of the 10,000 or so hedge funds spawned by this giddily rich time. Nearby is Daniel Loeb, of Third Point, one of the better-known “activist” hedge funds, who hopes to move soon into a 10,700-square-foot, $45 million penthouse at l5 Central Park West, a Manhattan monument to the new gilded age. Gliding easily between them is art dealer Larry Gagosian, so successful at selling Bacons and Serras to Wall Street’s new titans-including to Cohen-that he now travels in his own private jet and has his own helicopter to take him to it.

But here’s the odd thing: despite the beauty of the ocean view, nearly all the guests have their backs to it. Cohen is deep in conversation with a colleague who seems to be pitching him a deal. Loeb hovers close to his wife, a former yoga teacher. Gagosian is near his stunning young girlfriend. No one notices the clouds that are, quite literally, on the horizon. Snap.

Six weeks later, the photograph is cracked and sepia-toned, curling at the edges, a historic print. In just that short time, the storm has hit and nothing looks the same.

It may be premature to say our gilded age has ended. Third Point dropped 10 percent in October, bringing it down 27 percent for the year, but Daniel Loeb is still moving into his extravagant new apartment. Steven Cohen’s SAC was down 11 percent in October and 18 percent for the year to date, but that still leaves him plenty of money to add a second ice-skating rink to his Greenwich, Connecticut, estate. And Larry Gagosian is still selling plenty of art.

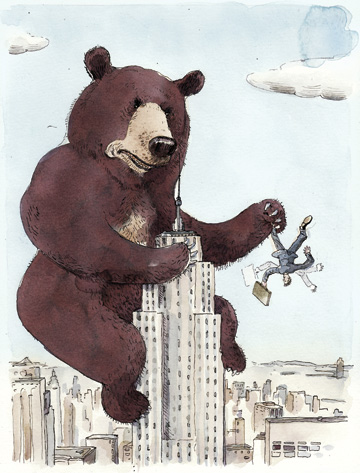

What’s definitely gone-along with Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns-is leverage, at least to the dizzying degree it was recently used by Wall Street’s investment banks, hedge funds, and private-equity firms to parlay each dollar of their assets into $10, $20, even $30 or more of credit to make gargantuan deals and profits. The credit crunch has made such leverage as quaint as the market in Dutch tulips. Without it, Wall Street salaries have already started drifting gently back to earth like so many limp balloons.

Gone, too, are jobs-lots and lots of them. Along with a sizable portion of Lehman’s 26,000 worldwide, and Bear Stearns’s 14,000, Wall Street firms across the board-even Goldman Sachs-are cutting back, and that pain radiates out to the limousine drivers and caterers and lawyers and personal trainers and restaurant owners and real-estate brokers who rely on Wall Street clients, not to mention to the many nonprofits and charities that have grown accustomed to Wall Street money. The latest estimate of jobs New York will lose, both on and off Wall Street, is l60,000. Governor David Paterson says the state’s budget deficit has already reached $12.5 billion. In New York City, where Wall Street accounts for more than a quarter of the tax revenues, Mayor Michael Bloomberg thinks the financial-sector crisis will leave a $2 billion hole in the next fiscal year’s budget.

Almost everyone has lost something-if not their jobs, then 25 to 50 percent of their retirement savings-and nearly everyone is glum, anxious, hung over. Prudence is the watchword now: sackcloth after the brilliant silks and brocades of the gilded age. The day after Lehman Brothers went down, a high-end Manhattan department store reportedly had the biggest day of returns in its history. “Because the wives didn’t want the husbands to get the credit-card bills,” says a fashion-world insider. A prominent designer says ruefully, “People really aren’t shopping at all unless there’s a deal or sale. It’s pretty dramatic-they have the stores at their mercy.”

Even those who have plenty left to spend aren’t spending it. “I ran into a couple I always see at the antiques show,” one Upper East Side woman recounts of her visit to the Armory show on Park Avenue. “They always buy something fairly grand. ‘What have you bought this time?’ I asked. ‘Oh, nothing!’ they said. ‘We’d feel … ashamed.'” Another Upper East Side woman often goes from lunch at Michael’s restaurant on West 55th Street to Manolo Blahnik a block away to pick up a $600 or $700 pair of shoes as “retail therapy.” No more. “I was at Michael’s yesterday and was thinking, Oh, Manolo’s … But then I thought, Why? Why do that? It just doesn’t feel good.”

A Penny Saved

Only months ago, ordering that $1,950 bottle of 2003 Screaming Eagle Cabernet Sauvignon at Craft restaurant or the $26-per-ounce Wagyu beef at Nobu, or sliding into Masa for the $600 prix fixe dinner (not including tax, tip, or drinks), was a way of life for many Wall Street investment bankers. “The culture was that if you didn’t spend extravagantly you’d be ridiculed at work,” says a former Lehmanite. But that was when there were investment banks. Now many bankers, along with discovering $15 bottles of wine, are finding other ways to cut back-if not out of necessity, then from collective guilt and fear: the fitness trainer from three times a week to once a week; the haircut and highlights every eight weeks instead of every five. One prominent “hedgie” recently flew to China for business-but not on a private plane, as before. “Why should I pay $250,000 for a private plane,” he said to a friend, “when I can pay $20,000 to fly commercial first class?”

The new thriftiness takes a bit of getting used to. “I was at the Food Emporium in Bedford [in Westchester County] yesterday, using my Food Emporium discount card,” recounts one Greenwich woman. “The well-dressed wife of a Wall Street guy was standing behind me. She asked me how to get one. Then she said, ‘Have you ever used coupons?’ I said, ‘Sure, maybe not lately, but sure.’ She said, ‘It’s all the rage now-where do you get them?'”

One former Lehman executive in her 40s stood in her vast clothes closet not long ago, talking to her personal stylist. On shelves around her were at least 10 designer handbags that had cost her anywhere from $6,000 to $10,000 each.

“I don’t know what to do,” she said. “I guess I’ll have to get rid of the maid.”

Why not sell a few of those bags?, the stylist thought, but didn’t say so.

“Well,” the executive said after a moment, “I guess I’ll cut her from five days a week to four.”

There were, to be sure, some big-name “blowups” as the market began to implode. Here was Sumner Redstone, chairman of Viacom and CBS, who had to sell $233 million worth of Viacom and CBS stock in order to pay down part of an $800 million loan. T. Boone Pickens, legendary Texas oilman, was another blowup, and so was Chesapeake Energy’s Aubrey McClendon, forced by a margin call to sell 94 percent of his 32 million company shares into the bear market. (Worth $2.2 billion last July, the shares were sold in October for $569 million.) Kirk Kerkorian, 91, has lost about $12 billion on his 54 percent ownership stake in MGM Mirage, the casino and hotel operator that owns almost half the hotel rooms on the Las Vegas Strip, including those in the Bellagio, the MGM Grand, the Mirage, and Mandalay Bay. The company’s stock is down 86 percent this year, and its bonds were downgraded deeper into junk status in October. Kerkorian has reportedly told friends that he “lived one year too long.” (He now claims he never said it.) Nevertheless, he and the other three men are all still billionaires.

Wealth

Greenwich estate manager Jacqueline de Bar describes how wealthy locals are cutting back: letting the pastures grow, canceling the leaf blowers, doing the storm windows themselves. At Betteridge Jewelers-known as Wall Street’s jeweler-third-generation owner Terry Betteridge says a lot more customers are coming in since the meltdown, to sell, not buy. “I’ve seen some bad ones in the last two months,” he says. “I know a Wall Street guy who’s literally been selling jewelry to make the mortgage payments. He and his wife came in together, bringing things to sell…. Just this morning, we took in a $2.7 million lot. An amazing collection, some of the best jewelry in the world, everything signed-extraordinary things I couldn’t buy before. No matter what I bid wasn’t enough. Now I can.”

Down the street is Consigned Couture, where Wall Street wives come to unload last year’s designer clothes and accessories. Some send their housekeepers, others their daughters. “My calendar is booked a month ahead, up to eight appointments a day,” says owner Dolly Ledingham. That’s sellers. Buyers? Not so much. “They used to come in to spend $1,000. Now they spend $100.”

In this global economy, the age’s excesses and aftermath are spread wide, nowhere as vividly as in London. Notting Hill was the epicenter of London’s gilded age, where every driveway, it seemed, had a Maserati, every mansion a makeover, often including an underground pool. Now, says Sunday Times columnist Rachel Johnson, who chronicled the invasion of the financiers in her 2006 novel, Notting Hell, bankers are staggering around like lost souls, while their wives gather at 202, the stylish Westbourne Grove restaurant in Nicole Farhi’s boutique, to share their fears. “What they’re crying about is they’ve lost all their stock, and their houses are worth less than they were,” says Johnson of the wives, “but they’re really upset that on January 31 they have to pay huge tax bills. Even though they don’t have the cash anymore, the liability remains on what they earned before.”

In London as in New York, Lehman bankers are among those hardest hit. One in his mid-30s says that for two weeks after the bankruptcy the New York office was cloaked in ominous silence-no communication from the 31st floor to London’s Canary Wharf. After the filing, the banker and his colleagues were all told to keep coming to work, or else possibly not get paid. So they came in and played Pac-Man and Tetris. Finally, he says, the whole London-based fixed-income group was called into an auditorium and “made redundant” by a representative from the accounting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers. That was it for the banker’s Lehman career-and the $1 million in company stock that a friend says he lost.

On a higher level, major figures on the London financial scene have lost billions-tens of billions, in some cases. Only last May, Indian tycoon Lakshmi Mittal, who owns the world’s largest steel company, paid $230 million for Israeli-American hedge-fund tycoon Noam Gottesman’s Georgian mansion, in Kensington Palace Gardens-a London record. Now, amid the commodities plunge, Mittal is said to have lost some $50 billion, and to be down to his last $16 billion. Michael Spencer, founder of icap, the interdealer broker, watched roughly $700 million of his stake in the firm go up in smoke as the market came down.

Another name bandied about is that of Nat Rothschild. The 37-year-old son of Lord (Jacob) Rothschild, he some years ago weaned himself from a dissolute life, gave up alcohol (even his family’s Château Lafite Rothschild wine), and turned to the serious work of making money, eventually becoming co-chairman and rainmaker of the New York-based hedge fund Atticus Capital. Rothschild continued to live well-very well, with homes in London, Manhattan, Moscow, Greece, and Klosters, Switzerland, where he established his principal residence, where there are no English taxes. He went from home to home, the London Daily Mail reports, in an elaborately equipped Gulfstream jet, supposedly always with two uniformed butlers, rarely staying more than four days in any locale. But the rainmaking worked: Atticus pulled in eye-popping returns, and Rothschild probably made more than $800 million-all in advance of the $750 million or so he’d one day inherit. “He has a very difficult relationship with his father,” suggests London-based columnist Taki Theodoracopulos. “I think his father would have liked him to be more interested in houses and furniture. This guy just cares about making money.”

Now Atticus has racked up staggering losses of $7.5 billion. Its Atticus European fund, once worth $8 billion alone, was down 43 percent by early October.

Usually, December is the year’s most festive time in New York. Wall Street bankers either have their bonuses or know what they will be. Their wives have bought new gowns for the season’s charity balls-the Metropolitan Museum’s acquisition-fund benefit and the New York Botanical Garden’s Winter Wonderland Ball, and more, at ticket prices ranging from $400 to $15,000. Then it’s off to St. Barth’s for sun worshippers, Aspen for skiers.

But not this year.

Privately, some New York benefit organizers wonder if even half the stalwarts will show up. On St. Barth’s, rental villas are usually booked by early fall; this year, many were available as of early November. At Aspen’s St. Regis hotel, Christmas week was still available, at $13,920 for two.

For bankers and hedgies, the fear this holiday season is not of bonuses reduced or denied-that’s expected. The real fear is of massive layoffs and massive redemptions by hedge-fund investors, of another Wall Street bloodbath in early ’09.

Soon, says wealth manager Alexandra Lebenthal, the Blake and Grigsby Somersets will find out what they’re really made of. “Were their lifestyle, friends, and even marriage based on living a certain way, without limits, or do they have the values to make it through the tough times?”

Philip K. Howard, a New York lawyer and social critic whose new book is Life Without Lawyers, sees a sea change which was overdue. Every 30 years or so, he notes, the country has to redefine its social values. We’ve just reached the next time. “So this end of the new gilded era-it’s like a bucket that spilled, and finally the money spilled out, and we were left with a culture whose sense of purpose and responsibility were lacking. And now there’s a real need for people, and society as a whole, to rethink and re-structure their values.”

“I may be the only one who’s thrilled by this recession,” says the wife of one London private-equity manager who took his lumps this fall. “It just means we’ll have to get possibly another job. But the bottom line is that it is just money. When you realize that you have enough-your health and a roof and good food and your family-you have to just feel lucky.”

Happy New Year.

by Michael Shnayerson January 2009

Source: VANITYFAIR

1 thought on “Profiles in Panic: The World of the Rich Collapses”