– When Hindenburg Omens Are Ominous (ZeroHedge, Aug 9, 2015):

I’ve frequently noted that Hindenburg “Omens” in their commonly presented form (NYSE new highs and new lows both greater than 2.5% of issues traded) appear so frequently that they have very little practical use, especially when they occur as single instances. While a large number of simultaneous new highs and new lows is indicative of some amount of internal dispersion across individual stocks, this situation often occurs in markets that have been somewhat range-bound.

Still, when we think of market “internals,” the number of new highs and new lows can contribute useful information. To expand on the vocabulary we use to talk about internals, “leadership” typically refers to the number of stocks achieving new highs and new lows; “breadth” typically refers to the number of stocks advancing versus declining in a given day or week; and “participation” typically refers to the percentage of stocks that are advancing or declining in tandem with the major indices.

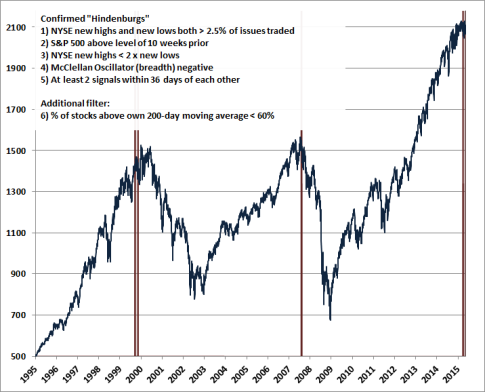

The original basis for the Hindenburg signal traces back to the “high-low logic index” that Norm Fosback created in the 1970’s. Jim Miekka introduced the Hindenburg as a daily rather than weekly measure, Kennedy Gammage gave it the ominous name, and Peter Eliades later added several criteria to reduce the noise of one-off signals, requiring additional confirmation that amounts to a requirement that more than one signal must emerge in the context of an advancing market with weakening breadth.

Those refinements substantially increase the usefulness of Hindenburg Omens, but they still emerge too frequently to identify decisive breakdowns in market internals. However, one could reasonably infer a very unfavorable signal about market internals if leadership, breadth, and participation were all uniformly negative at a point where the major indices were still holding up. Indeed, that’s exactly the situation in which a Hindenburg Omen becomes ominous. The chart below identifies the small handful of instances in the past two decades when this has been true.

While the measures of market internals that we use in practice are far more comprehensive, the evidence from leadership, breadth and participation above provides a fairly obvious signal of internal dispersion in the market. In our view, that dispersion is a strong indication that investors are shifting toward greater risk aversion. In an obscenely overvalued market with razor-thin risk premiums, a shift in the risk-preferences of investors has historically been the central feature that distinguishes a bubble from a collapse.

In my view, dismal market returns over the coming decade are baked in the cake as a result of extreme overvaluation at present. An improvement in market internals, however, would reduce the immediacy of our downside concerns. While a decision by the Federal Reserve to postpone the first interest rate hike might prompt a shift to more risk-seeking speculation, this outcome is not assured. The key indicator of risk-seeking would still be the behavior of market internals directly, not the words or behavior of the Fed. So we remain focused on market internals. In any event, waiting to normalize monetary policy may defer, but cannot avoid, a market collapse that is already baked in the cake. The Fed has only encouraged the completion of the current market cycle to begin from a more extreme peak. As we saw in 2000-2002 and again in 2007-2009, until and unless investors shift toward risk-seeking, as evidenced by the behavior of market internals, monetary easing may have little effect in slowing down a collapse.

Read Hussman’s full letter here…

* * *

Interesting…