– Argentina’s Modest Proposal: Buy Bonds Or Go To Jail (ZeroHedge, May 11, 2013):

While Argentina’s recent extraordinary attempts at central planning have been widely documented, ranging from freezing supermarket prices in a (failed) attempt to control inflation, to banning advertising in a (failed) attempt to weaken the private media, so far nothing has worked at stabilizing the economy and preventing the collapse in the domestic currency (if leading to such humorous viral videos as #mequieroir). Ironically, this is both good and bad news. It is good news because as we showed two days ago, even the ludicrous speed rise in the Nikkei has been a snail’s pace compared to that other unknown “Nation 1.” We can now reveal that while Japan is Nation 2, Nation 1 is that inflationary basket case Argentina, and specifically its Merval stock index.

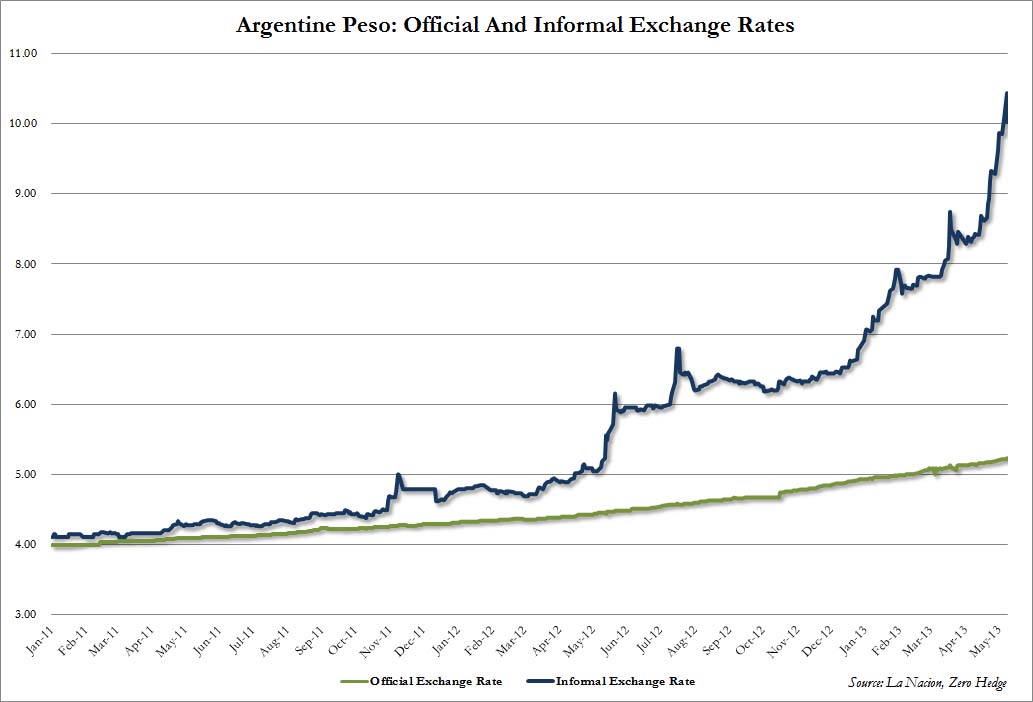

Of course, the surge in the stock index is nothing more than a reflection of the ongoing collapse in the economy, which in turn is reflected not by the official, government controlled exchange of the ARS (just try buying dollars at the official rate) which closed the week at a rate of 5.24 to the dollar, then certainly the black market one, showing just how weak the currency is for those who actually want to buy dollars in Argentina, which just hit a record high of over 10. In fact, as the chart below shows, when one factors in the 80% collapse in the real, unofficial exchange rate over the same time period, the stock index has barely kept up.

Furthermore, it is merely a time before the runaway inflation pushes corporate input costs so high, that not even the rise in the stock market can preserve wealth.

Still think soaring stock prices in the New Normal are an indication of anything but a collapse in the economy manifested by either current, or discounted, plunges in the purchasing power of a sovereign’s currency?

And just to make sure there is no confusion, the full context here is that while the rest of the G-0 world at least has each other’s central banks to fund mutual debt purchases, Argentina has been locked out from the global community for a variety of reasons. And yet, like any other Keynesian follower, the nation is desperate to borrow from the future in order to grow government now. However, without access to capital markets how will the country with the imploding currency do this?

Simple.

Argentina’s president Kirchner, a keen observer of recent events in Cyprus, has figured out a way to kill two birds with one stone, namely attempt to put an end to tax evasion, and fund the capex of the recently nationalized state oil company YPF (now that its former owner, Spainish Repsol, is less than keen to keep investing in its former Argentine subsidiary). To do that she will present the local tax-evading population (pretty much anyone with any disposable income and savings) with a simple choice: buy a 4% bond to fund YPF “growth” or go to prison.

From Bloomberg:

President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner wants tax evaders hiding about $160 billion in dollars to help finance Argentina’s oil-producing ambitions. Her offer: Buy a 4 percent bond or face the prospect of jail time.

The tax authority announced the plan May 7, highlighting its information-sharing agreements with 40 nations and warning Argentines who don’t use the three-month amnesty window that they risk fines or arrest. Evaders have two options for their cash and the only one paying interest will be a dollar bond due in 2016 to finance YPF SA (YPF), the state oil company. The 4 percent rate is a third the average 13.85 yield on Argentine debt and less than the 4.6 percent in emerging markets.

Speaking of YPF’s growth, we made it very clear a year ago when we reported on the latest “banana republic” nationalization of formerly efficient and private assets, that it was only a matter of time before an overarching government’s epic misallocation of resources, leads to epic inefficiencies, and a liquidity scramble. It is not rocket science: only hardcore socialists can harbor any hope that a government is efficient at allocating capital, especially when one nets out the 50% or so in corruption “externalities” that are incurred along the way, be it in Argentina or the US. Once again we were right:

A year after seizing YPF, Fernandez is funneling more money into the nation’s energy industry as the government struggles to boost production from the world’s third-biggest shale oil reserves. With Argentina already committed to pumping $2 billion of central bank reserves into a fund for energy investments and the highest borrowing costs in emerging markets keeping it from issuing debt abroad, the government is eyeing the billions of undeclared dollars that Argentines hold to help shore up reserves that have dwindled to a six-year low.

“The authorities need to take steps to open up external resources in the energy sector and to finance the Treasury and local governments,” said Sebastian Vargas, a New York-based analyst at Barclays Plc. “The amnesty is not negative for markets but it’s disappointing because they do little to solve balance-of-payment difficulties.”

There are some cynics who will say what Argentina is doing on a semi-voluntary basis is what that other bastion of wealth expropriation, the European Union, did to Cypriot savers. They will be right of course, if only for the simple reason that Argentina does not know precisely where all the “illegal” tax-evading, offshore (and onshore) capital is held.

Argentines have at least $160 billion of undeclared funds, equal to about 36 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product, and $40 billion are hidden inside the country, Vice Economy Minister Axel Kicillof said at the May 7 press conference where he and other senior officials presented the amnesty.

Many Argentines hide assets to avoid a 35 percent income tax and a levy of as much as 1.25 percent on their personal wealth. Undeclared assets are also beyond the reach of the government, which in 1989 seized bank certificates of deposit in exchange for bonds and in 2002 converted dollar deposits into pesos.

In other words, unlike in Europe, where Russia’s ‘tax-efficient’ billionaires had a bright shining red light blinking over Cyprus saying “we are here” (a light that is now blinking over Luxembourg, Lichtenstein and of course, Switzerland, not to mention other global offshore tax havens), in Argentina the government first has to find the money. Which is why its initial recourse is the conventional one: simple threats.

Those joining the plan would be immune from prosecution and won’t be forced to pay past-due taxes, said Ricardo Echegaray, head of the tax agency. The search for evaders, which includes cross-checking information on income and personal wealth reports with purchases of real estate and cars, foreign travel and credit card purchases, will continue, Echegaray said.

“You better bring your dollars back because we will find you,” Echegaray said at the May 7 press conference. Last year, tax collection in South America’s second-largest economy rose to 37 percent of gross domestic product from 16.5 percent in 2002, according to Economy Ministry data.

Former Vice Economy Minister Roberto Feletti, who is now a congressman for Fernandez’s Victory Front alliance, said the government expects to attract at least $5 billion under the program.

Good luck with that – the only thing Argentina will succeed is in forcing tax evaders to hide their money even deeper into the global shadow economy.

The amnesty program will probably fail because its benefits don’t outweigh investors’ mistrust of the government’s ability to rein in inflation, cut spending, attract foreign investment and restore confidence in the currency, according to Moody’s Analytics Inc.

“The problem the government faces is lack of credibility and lack of confidence,” Juan Pablo Fuentes, an economist at Moody’s, said in a telephone interview from West Chester, Pennsylvania. “That money is potentially there, it could come back eventually, but there needs to be a lot of changes. These bonds are not going to have any real impact.”

And in the meantime YPF, which can’t afford to wait on capital infusion, will have less and less cash with which to operate and grow, until finally it is mothballed, dimming the one bright light in Argentina’s economy, and leading to an even faster economic contraction, even more rapid devaluation of the Peso, if only in the black market of course, and an ever faster surge in inflation.

But at least the stock market will be off the charts: sounds like a fair exchange for yet another economy sent to an early grave by central planners.