– A Bright Future For Greeks:”Now I Clean Swedish Shit” (ZeroHedge, Sep 7, 2012):

One look at the short squeeze in the EURUSD, coupled with the endless jawboning out of Europe, and one may be left with the faulty impression that Europe has been magically fixed and that Greece couldn’t be more delighted to remain in the Eurozone. One would be wrong. This is what is really going on in Europe:

As a pharmaceutical salesman in Greece for 17 years, Tilemachos Karachalios wore a suit, drove a company car and had an expense account. He now mops schools in Sweden, forced from his home by Greece’s economic crisis.

“It was a very good job,” said Karachalios, 40, of his former life. “Now I clean Swedish s—.”

That more or less explains everything one needs to know about the “fixing” of Europe.

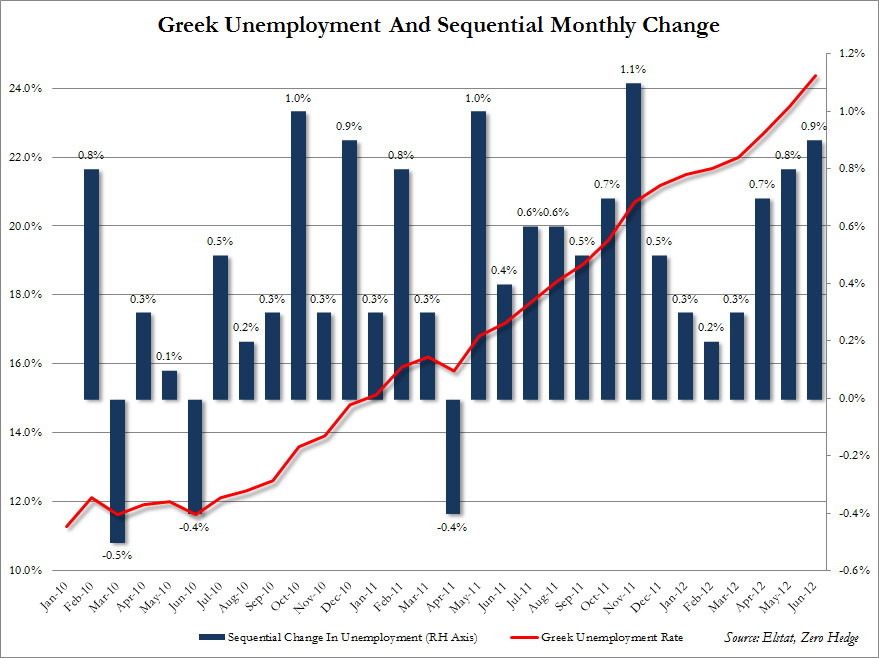

Of course, those who saw our chart from yesterday which showed Greek unemployment rising by 1% in one month to a record 24.4% will hardly find this surprising.

For all those others who need a personal anecdote to grasp just how fixed Europe is, we hand it off to Bloomberg.

Karachalios, who left behind his 6-year-old daughter to be raised by his parents, is one of thousands fleeing Greece’s record 24 percent unemployment and austerity measures that threaten to undermine growth. The number of Greeks seeking permission to settle in Sweden, where there are more jobs and a stable economy, almost doubled to 1,093 last year from 2010, and is on pace to increase again this year.

“I’m trying to survive,” Karachalios said in an interview in Stockholm. “It’s difficult here, very difficult. I would prefer to stay in Greece. But we don’t have jobs.”

Greece is in its fifth year of recession, with the economy expected to contract 6.9 percent this year, the same as in 2011, according to the Athens-based Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research. Since 2008, the number of jobless has more than tripled to a record 1.22 million as of June, out of a total population of 10.8 million.

“In Greece, there was no future,” said Ourania Michtopoulou, who moved with her husband to Sweden in 2010 after both lost textile industry jobs in Thessaloniki, where they had a comfortable life with a house and car. “Here, I can hope for something good to happen. Maybe not for me — I’m 48 — but maybe for my children.”

Their family now crams into a small apartment, while her husband, Nikos, works for a landscaper and her teenage children struggle with Swedish lessons.

“It was not easy for them,” she said. “My daughter said lots of times, ‘I hate Sweden — I want to go home.’”

Karachalios began his career in pharmaceutical sales after his mandatory military service, working at three different companies in the southern city of Patras. He married a Chinese woman he met at the 2004 Athens Olympics, had a daughter, and divorced.

“You can plan, you can organize, you can make plans for 10 years, 20 years, but you don’t know what life brings,” he said.

An intense man with flecks of gray in his thinning black hair, Karachalios said he has lost 20 to 30 pounds since moving to Sweden. His hands are stained with grime. Instead of the suits and ties he once wore, he now dresses in jeans and work boots. His suits remain in Greece.

In Homer’s Odyssey, Telemachus is the son of Odysseus, a Greek hero who spent 10 years struggling to return home from the Trojan War. Karachalios was named after a great-uncle who was a favorite of his parents.

Karachalios’s troubles began in early 2010 when the Greek government, which provides health care, forced drugmakers to cut their prices by as much as 27 percent. To reduce costs, his then-employer PharmaSwiss fired him and two other salesmen, leaving his former supervisor to manage the accounts, he said. Karachalios searched for jobs and eventually spent two months in 2011 as a telemarketer in Athens. He quit after not being paid. An ill-fated attempt to start a retirement home cost him months of work and most of his savings.

Determined to move, Karachalios considered Australia before rejecting the immigration process as too expensive. He had a friend in Sweden, had visited before and knew its reputation.

“I knew they were very organized,” he said. “Everyone pays their taxes and it’s fair. There is no cheating.”

Karachalios arrived in March. His friend helped him find a room to rent and he pays 4,500 Swedish krona ($670) a month for a room in a quiet apartment complex that houses other immigrants, many from the Middle East.

His studio has no stove or oven, just a hot plate and microwave. He has a single dish, and when he has a guest, he eats out of a plastic container that used to hold feta cheese. A tiny Greek flag is taped to the wall. The room came with a television though Karachalios said he never watches. In the evenings, if he has the energy, he studies Swedish.

Because of his background in health care, Karachalios at first applied for jobs caring for the elderly. He was rejected without an interview because he didn’t speak Swedish.

To find a job, he began knocking on doors of restaurants and janitorial companies, and eventually found a position cleaning rental houses. It was hard, lonely work that didn’t allow a break for lunch, he said. His first week wasn’t paid because he was told he was being trained. After his second week, when he was paid for only 32 hours instead of the 40 he said he worked, he wasn’t called back.

In Greece, Karachalios was paid between 2,500 and 3,000 euros ($3,143-$3,772) a month, after taxes. In Stockholm, he makes 80 krona an hour. Based on a 40-hour work week, that equals about $1,907 a month.

…

“I was doing something more glamorous but I don’t mind this work,” he said. “I feel alive again. When you are unemployed too long, it’s very hard. I was angry all the time.”

Karachalios wasn’t paid until mid-August for work he did in July. In the meanwhile, he lives frugally, saving half-smoked cigarettes while he waits for his parents to wire money. He also worries about finding another job, which will be necessary once school resumes and the cleaning contract ends. If he can’t find a permanent job in Stockholm, he said he may move with his daughter to Shanghai, where his ex-wife lives.

“I don’t have anywhere else to go and work, and it would be helpful for my daughter,” he said.

…

Karachalios wakes at 5 a.m. with the sun already up because of the long Swedish summer days. He checks Facebook on his phone for news from Greece and takes the subway one stop to Rinkeby, a gritty working-class neighborhood. Near the station is a parking lot where people without homes sleep in their cars, leaving their shoes and bottles of water outside the doors.

…

After a cigarette with his co-workers — all immigrants from Greece — Karachalios piles into the van for the 45-minute drive to the outskirts of Uppsala, a small city north of Stockholm. Today’s job is to finish cleaning the elementary school they began working on yesterday. They start at 7:30 a.m. and work 2 1/2 hours before breaking. For lunch, they share their food, with Karachalios bringing fried meatballs for the group.

…

Karachalios is charged with cleaning the dozens of double- paned windows, which takes its toll on his back and shoulders. On other days, he cleans floors. In his pocket, he carries a razor blade for scraping the gum off linoleum.

…

“I’m tired of all this,” he said. “I want to close my eyes and wake up in 10 years and not have to worry.”

…

“To get to be 40 years old, it’s very hard to accept that your life is going to be like this,” Karachalios said.

Ah…. “European utopia.“

Continue reading here.