Exploding pension fund shortfalls are blowing billion-dollar holes in the balance sheets of some of the Chicago area’s biggest companies, forcing them to make huge contributions to retirement plans at a time when cash flow and credit are already under stress.

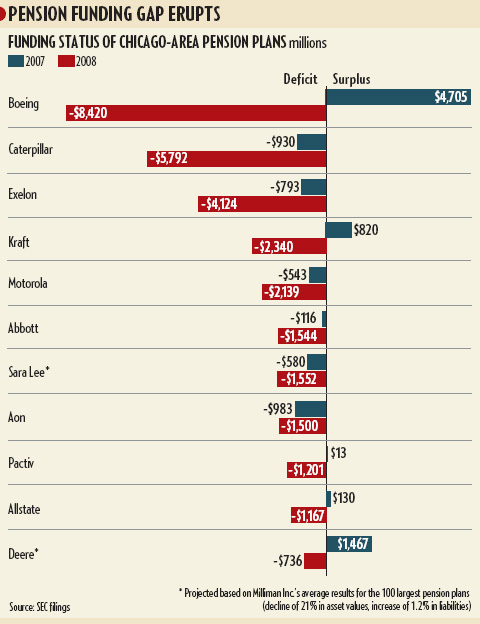

Boeing Co.’s shareholder equity is now $1.2 billion in the hole thanks to an $8.4-billion gap between its pension assets and the projected cost of its obligations for 2008. At the end of 2007, Boeing had a $4.7-billion pension surplus. If its investments don’t turn around, the Chicago-based aerospace giant will have to quadruple annual contributions to its plan to about $2 billion by 2011.

Stock market losses also pounded pension funds at Abbott Laboratories Inc., Caterpillar Inc. and Exelon Corp., with others sure to emerge as companies file their annual financial reports with the Securities and Exchange Commission in coming weeks.

The pension gaps underscore a growing conundrum. Unfunded pension liabilities have to be subtracted from shareholder equity, weakening balance sheets at a time when it’s already tough to borrow money. Barring a reprieve from Congress, companies may be forced to make more layoffs or curb capital investments to divert cash to shore up pensions.

“There are companies out there faced with paying their pension plan or staying in business,” says Mark Ugoretz, president and CEO of the ERISA Industry Committee, a Washington, D.C., lobbying group. ERISA refers to the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, which sets standards to ensure pension plans are sufficiently funded.

The Chicago companies are symptomatic of nationwide woes. Last year, the 100 largest corporate pension funds in the U.S. saw their net assets decline by 21%, while liabilities increased 1.2%. Applying those averages to any of the region’s top funds puts almost all of them into the red by at least $1 billion.

PRESSURE MOUNTS

The situation is far worse at companies that entered 2008 with plans already in poor shape. They are now even harder-pressed to come up with huge increases in pension fund contributions to erase the gap in seven years, as federal law requires.

A Boeing spokesman says the pension deficit is “clearly a situation we don’t like,” but adds that the company’s credit rating hasn’t been affected.

Stricter federal pension-funding requirements, enacted when the stock market was riding high, threaten to undermine the economy further. Business interests are lobbying for more time to close the gaps, but with lawmakers focused on the housing and banking crises, the issue hasn’t gained much traction in Washington.

As a result, “many of the country’s largest employers are being forced to make short-term trade-offs between maintaining employment and funding long-term obligations,” Sears Holdings Corp. Chairman Edward Lampert wrote in a note to shareholders last week.

Hoffman Estates-based Sears, which announced the closings of 24 stores this year, expects its pension expense to soar as high as $175 million this year from $1 million last year due to the markets’ decline.

RIPPLE EFFECTS

Underfunded pensions also are forcing borrowing costs higher for some companies.

At Peoria-based Caterpillar, shareholder equity dropped more than 25% from the previous year after the company booked a $5.8-billion pension shortfall and its plan went from 93% funded to 61% funded.

That means Cat has to pay an additional 1.5 percentage points of interest to keep its untapped credit lines intact, according to SEC filings. Its pension assets sank 30% last year, and this year’s contribution will more than double to about $1 billion. A Cat spokesman declines to comment.

DOUBLE WHAMMY

A decline in interest rates last year also fueled widening pension liabilities, says Lynn Dudley, senior vice-president of policy for the American Benefits Council, another Washington, D.C., group lobbying for more time to fund plans.

Generally, the current value of a future obligation goes up when interest rates come down. In essence, last year’s drop in stock prices and interest rates was a double whammy for pension funds, Ms. Dudley says.

“The law kind of slams you. In extreme markets, it’s really unpredictable,” she says. Absent relief from Congress, she says, “there have been some layoffs, and there are going to be more layoffs” to save cash for pension contributions.

The most notable Chicago-area exception is Moline-based Deere & Co., which began 2008 with a plan that was 17%, or $1.5 billion, overfunded.

Deere may have escaped the worst of the 21% average decline in assets. The company’s fiscal year ended Sept. 30, before the worst of the stock downturn hit, and only 27% of its fund — far less than most — was in equities. A Deere spokesman declines to comment.

By: Paul Merrion

March 02, 2009

Source: Chicago Business