– Why America’s First National Supermarket Chain Just Filed For Bankruptcy… Again (ZeroHedge, July 20, 2015):

Back in December 2010, we were “stunned” when we learned that in a what was a clear case of a supermarket chain unable to pass through costs to consumers, the Great Atlantic & Pacific Company (“Great Atlantic”, “A&P” or the “Debtors”), which in 1936 became the first national supermarket chain in the US, would file for bankruptcy adding that “it is ironic that instead of passing through costs supermarkets are instead opting out to default”. Although perhaps even back then it was clear to A&P that the capacity of US consumer to shoulder higher prices is far worse than what the mainstream media would lead everyone to believe.

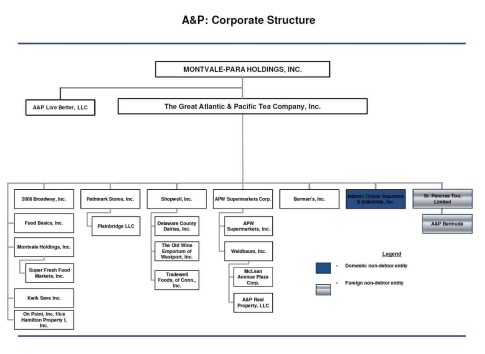

Fast forward to last night, when less than five years after its first Chapter 11 filing (and three years after emerging from a bankruptcy in March 2012 as a privately-held company part owned by Ron Burkle’s Yucaipa with a clean balance sheet including $490 million in new debt and equity financing), overnight Great Atlantic, which controls such supermarket brand names as A&P, Waldbaum’s, SuperFresh, Pathmark, Food Basics, The Food Emporium, Best Cellars, and A&P Liquors – filed for repeat bankruptcy, or as it is better known in restructuring folklore, Chapter 22.

So what happened in the intervening 5 years that caused the company which employes 28,500 workers (93% of whom are members of one of twelve local unions and who are employed by A&P under some 35 separate collective bargaining agreements) to deteriorate so badly that it burned through all of its post (first) petition cash and redefault?

In one word: unions.

Because just like in the case of comparable Chapter 22 (and subsequently liquidation) case of Twinkies maker Hostess, so A&P is blaming the unwillingness of its biggest cost center, its employees, to negotiate their way out of what will be an event in which at least half the company’s employees will be laid off.

Here is the full story, as narrated by Christopher W. McGarry, Great Atlantic’s Chief Restructuring Officer:

[Great Atlantic is] one of the nation’s oldest leading supermarket and food retailers, operating approximately 300 supermarkets, beer, wine, and liquor stores, combination food and drug stores, and limited assortment food stores across six Northeastern states. The Debtors’ primary retail operations consist of supermarkets operated under a variety of wellknown trade names, or “banners,” including A&P, Waldbaum’s, SuperFresh, Pathmark, Food Basics, The Food Emporium, Best Cellars, and A&P Liquors. The Debtors currently employ approximately 28,500 employees, over 90% of whom are members of one of twelve local unions whose members are employed by the Debtors under the authority of 35 separate collective bargaining agreements (collectively, the “CBAs”). As of February 28, 2015, the Debtors reported total assets of approximately $1.6 billion and total liabilities of approximately $2.3 billion.

A&P was founded in 1859. By 1878, The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company (A&P)—originally referred to as The Great American Tea Company—had grown to 70 stores. A&P introduced the nation’s first “supermarket”—a 28,125 square foot store in Braddock, Pennsylvania—in 1936 and, by the 1940s, operated at nearly 16,000 locations. The Tengelmann Group of West Germany’s purchase A&P in 1979 precipitated an expansion effort that led to the acquisition of, among others, a number of Stop & Shops in New Jersey, the Kohl’s chain in Wisconsin, and Shopwell. Due to a series of operational and financial obstacles, including high labor costs and fast-changing trends within the grocery industry, by 2006 A&P had reduced its footprint to just over 400.

In 2008, A&P acquired its largest competitor, Pathmark Stores, Inc., in an effort to continue expanding its brand portfolio and, in doing so, became the largest supermarket chain in the New York City area. A&P continued to experience significant liquidity pressures on account of burdensome supplier contracts, overwhelming labor costs, and other significant legacy obligations. Moreover, A&P had become highly leveraged and was unable to operate as a profitable company.

Did we mention this is the second Great Atlantic bankruptcy in under five years? Yes, we did.

This is the Debtors’ second bankruptcy in just five years. A&P previously filed the 2010 Cases seeking to achieve an operational and financial restructuring. The 2010 Cases were difficult and challenging. Unfortunately, despite best efforts and the infusion of more than $500 million in new capital in the 2010 Cases, A&P did not achieve nearly as much as was needed to turn around its business and sustain profitability. For example, during the 2010 Cases, A&P decided against closing approximately 50-60 underperforming stores in their supermarket portfolio in favor of preserving the jobs in those stores. Instead, A&P pursued a financial restructuring and negotiated a reduction in labor and vendor costs to attempt to return these stores to profitability. Those efforts have failed. Similarly, A&P did not seek to address its multi-employer pension and certain other significant legacy obligations. These obligations have been a drain on the Company for the entire post-emergence period. From February 2014 through February 2015, A&P lost more than $300 million.

Which was more than half of the total exit funding Great Atlantic obtained as part of its first bankruptcy process. And now comes the blame:

In addition to their weak performance, the Debtors’ businesses remain plagued by other limitations that have prevented them from operating in an efficient and profitable manner. Among other things, most of the Debtors’ CBAs contain “bumping” provisions that require A&P to conduct layoffs by seniority, i.e., by terminating junior union members before more senior members. Bumping provisions also have an inter-store component: upon the closing of a store, terminated union employees are permitted to take the job of a more junior employee at another store (resulting in the most junior employee at that store losing his or her job). As a result, the closing of one store results in increased salaries—the same high salaries that may have in part precipitated the store closing—being transferred to another (possibly profitable) store. In fact, the Debtors have continued to operate certain stores that regularly operate at a loss because continuing to operate such stores at a loss is less costly to A&P than the bumping costs (combined with other “legacy” costs) that would be triggered by closing such stores.

It’s not just the unions: A&P takes at least some blame for being unable to properly invest CapEx into growth, instead squandering its cash on unresolved cash drains: look for this excuse to be prevalents during the mass bankruptcies to follow in the next few years when hundreds of companies which are buying back stock now will lament loudly they did not invest in their own future instead.

The Debtors’ deteriorating financial condition has also been compounded by the fact that, since emerging from the 2010 Cases, their unsustainable cost structure has prevented them from investing sufficiently in their businesses at a pivotal time in the competitive grocery industry, when their peers were investing heavily in new stores and existing store remodels, robust pricing initiatives, and were introducing technological advances and other initiatives to customize and improve the consumer experience. For example, under its plan of reorganization in the 2010 Cases, A&P was projected to invest over $500 million in capital improvements during the ensuing 5-year period. Since emergence, due to insufficient capital and declining operations, among other things, the Debtors have been able to deploy capex at scarcely more than half that rate. As a result, many of the Debtors’ stores have remained outdated and/or underinvested, making it difficult to attract and retain new customers during a crucial time of rebranding and rebuilding

And then, once the market realized A&P was in dire straits, it didn’t take long for the “JCPenney effect” to materialize and for suppliers to tighten vendor terms, draining the company of even more cash:

In addition to the historical pressures on their liquidity, as news of the Debtors’ continued financial challenges recently began to permeate throughout the market, a number of the Debtors’ suppliers and vendors began contacting management and demanding changes in payment and credit terms. Certain of the Debtors’ vendors have negotiated reduction in trade terms while others have demanded that the Debtors pay cash in advance as a condition for further deliveries. Although the Debtors have been working diligently with their advisors to resolve open vendor issues and avoid supply chain interruption, the actions taken by these vendors have further diminished the Debtors’ cash position by approximately $24 million in the weeks prior to the Commencement Date. Furthermore, on July 14, 2015, C&S Wholesale Grocers, Inc. (“C&S”) – the Debtors’ primary supplier of approximately 65% of all goods – issued a notice of default for non-payment of the $17 million deferred paymen.

The end result of this escalation of bad management decision and intransigent labor unions: “cash burn rates averaging $14.5 million during the first four periods of Fiscal Year 2015” which gave the company no choice but “to commence these Chapter 11 Cases as the only viable alternative to avoid a fire sale liquidation of the company.”

But why not try to do what the company tried in 2010 with its first bankruptcy, and get it right this time? Here is what happened the last time A&P bet on a post-bankruptcy existence:

Upon emergence from the 2010 Cases, the Debtors had $93.3 million of cash on their balance sheet and were prepared to invest in the growth of their business. In an effort to distance their businesses from the specter of bankruptcy, the Debtors designed and implemented an integrated marketing campaign intended to show customers that they had successfully emerged from bankruptcy and were prepared to move forward by offering highquality, localized products and enhanced services. The campaign entailed temporary price reductions and promotional advertising of the same through print, television, and radio. The Debtors’ investments did not, however, achieve the desired returns. Although the Debtors’ strategy drew more customers to their stores, such efforts were at the expense of margin income and the Debtors were not building productive, long-lasting relationships with their customers.

The Debtors’ thwarted attempts to attract and retain a new customer base compounded with their lingering legacy obligations drove down sales throughout many of their stores and negatively impacted their bottom line. During the first six months of fiscal year 2012, the Debtors were losing approximately $28 million per month. In an effort to turnaround their businesses, the Debtors’ management team launched a business strategy intended to restore stability and offset increasing post-restructuring liquidity pressures by scaling back the temporary price reductions they had implemented in certain of their stores because such reductions were showing diminishing marginal returns, setting up better controls over cash management, and monetizing a number of their real estate assets. Over a period of six to ten months, the Debtors generated over $200 million in asset sales, including sale leasebacks, while only relinquishing a handful of stores. The proceeds from these sales were used largely to pay down debt, while also giving the businesses with a slim liquidity buffer.

The Debtors’ business strategy showed signs of success and, by the end of fiscal year 2013, the Debtors had $192 million in cash, EBITDA was in the range of $121 million, and four-wall EBITDA was approximately $228 million. Still, due to the increasing competitive nature of the industry, during the same year, sales were down by 7.6% when compared to the prior year.

And this was during a period when the US economy was allegedly growing like gangbusters. Still, Yucaipa did not enjoy the prospect of losing its entire investment and pushed the company to sell itself. That did not work out:

After stabilizing their businesses during fiscal year 2013, the Debtors’ private equity owners began to evaluate potential strategic alternatives and, in Spring 2013, the Debtors retained Credit Suisse AG (“Credit Suisse”) to review such alternatives, including a possible going concern sale of the company. Credit Suisse initiated contact with a number of potential buyers and financial sponsors and marketed an equity-based sale of the company. Although the Credit Suisse marketing process garnered meaningful interest in the Debtors’ assets, the Debtors did not receive a viable offer for the stock of the company. The Debtors and their advisors ultimately determined that selling assets in smaller or one-off sales was not the best way to maximize recoveries and protect the interest of stakeholders, including their thousands of employees. Accordingly, plans to sell the Debtors’ businesses were placed in a state of suspension.

Right, they were concerned about the thousands of employees, sure.

In any event, then came the endgame, right at a time when the US recovery had never been stronger if one listens to the propaganda media:

The Debtors continued to suffer declining revenues. The Debtors showed a net loss of $305 million in Fiscal Year 2014, compared with a net loss of $68 million in Fiscal Year 2013. The Debtors generated a negative EBIT of -1.9% of sales or $105 million in Fiscal Year 2014, compared to a positive EBIT of 1.1% of sales, or $62 million, in Fiscal Year 2013. In 2014, the Debtors experienced a sales decline of approximately 6% when compared with 2013, and the trend continued into 2015.

The Debtors determined that they may continue to lose up to $10 to 12 million in cash per period during 2015. Additionally, the recent tightening of vendor terms has adversely affected working capital by approximately $24 million. Those situations would make them unable to maintain sufficient liquidity to meet the minimum cash requirements during 2015. Based on preliminary projections, the Debtors expected EBITDA of approximately $40 to $50 million in the 52 weeks ending February 29, 2016 (“Fiscal Year 2015”). With maintenance capital expenditures (approximately $35 million), higher cash contributions for workers’ compensation payments than expense (approximately $17 million), pension contributions greater than the actuarially-calculated book expenses (approximately $17 million), the tightening of accounts payables terms (approximately $24 million) and an eroding sales base, the company projected it would be unable to satisfy the $38 million in interest and principal due during Fiscal Year 2015.

So here is the CRO’s summary of the two key factors that precipitated Great Atlantic’s second, and final, bankruptcy. Chief among them: labor unions:

- Inflexible Collective Bargaining Agreements [aka Unions]. In addition to mandating direct labor costs, the CBAs contain a variety of different work rules that have functioned to hamstring the Debtors’ operations. For example, as stated above, most of the CBAs contain “bumping” provisions that require the Debtors to hire employees from a closed store location at a different nearby store and replace less senior employees at such store. Because any healthy store in close proximity to a store that is closing must take on the increased costs of retaining more senior level employees, “bumping” costs make it difficult and, in some cases, financially impractical, to close unprofitable stores notwithstanding that such stores continue to strain the Debtors’ balance sheet. For instance, one of the Debtors’ stores in Hackensack, New Jersey loses approximately $4 million per year but, under the applicable CBA, closing that store would require the Debtors to “bump” certain senior employees to a number of nearby stores— increasing labor costs by around $1.5 million per year. Preliminary analysis conducted by the Debtors’ advisors indicates that closing Initial Closing Stores alone could generate bumping costs as high as almost $14.8 million—making it more efficient to keep these stores open, absent relief from such provisions pursuant to the MA& Strategy.

- Crippling Legacy Costs. Historically, the Debtors’ legacy costs have not been aligned with the operating reality of their businesses. The Debtor’ labor-related costs make up 17.75% of sales while the total merchandising income before any warehousing/transportation and operating expenses is 35.48% of sales.

And then there was the usual red herring excuse:

- Competitive Industry. The Debtors also continue to face competitive pressure within the supermarket industry. For the reasons set forth herein, upon emerging from the 2010 Cases, the Debtors had a diminished capacity to invest in long-term capital projects. Thus, as the Debtors’ competitors realized new technology platforms, remodeled and enhanced their stores, and implemented localization strategies geared toward tailoring each store to specific neighborhood needs, the Debtors have not been able to invest in creating an operational distinction between their various “banners” and tailor stores to customer needs.

Which brings us to what happens next to Great Atlantic, which instead of simply throwing more good money after bad and hoping for a different outcome this time, is filing bankruptcy to break all existing labor union collective bargaining agreements (CBAs). Briefly, the company had conducted a pre-petition asset sale process and found that the best it can do is find buyers for just 120 stores, which employ 12,500 employees, for an aggregate purchase price of almost $600 million as part of a Stalking Horse process.

In other words, one failed acquisition and one failed bankruptcy later, A&P is about to go from 300 supermarkets to at most 120, and over 15,000 workers or well over half of the work force is about to be laid off.

The irony is that if it wasn’t for unions, it would be something else, like loading up on massive amounts of debt to repay Yucaipa’s equity investment, which would then be unsustainable once rates rose and once interest expense became so high it soaked up all the company’s cash flow (a harbinger of what is coming for the rest of US corporations who have rushed to issued trillions in debt just to pay their shareholders).

In conclusion, one can’t help but wonder if current events that are taking place behind the non-GAAP facade of America’s public companies, what is going on at A&P is far more indicative of the true state of the economy, an economy where due to both legacy constraints, bad management and, naturally, a deteriorating economy for all but the top 1%, the best that companies can do is support at most half their employees… after filing for bankruptcy of course.

Full A&P affidavit below