– China’s Credit Pipeline Slams Shut: Companies Scramble For The Last Drops Of Liquidity (ZeroHedge, March 27, 2014):

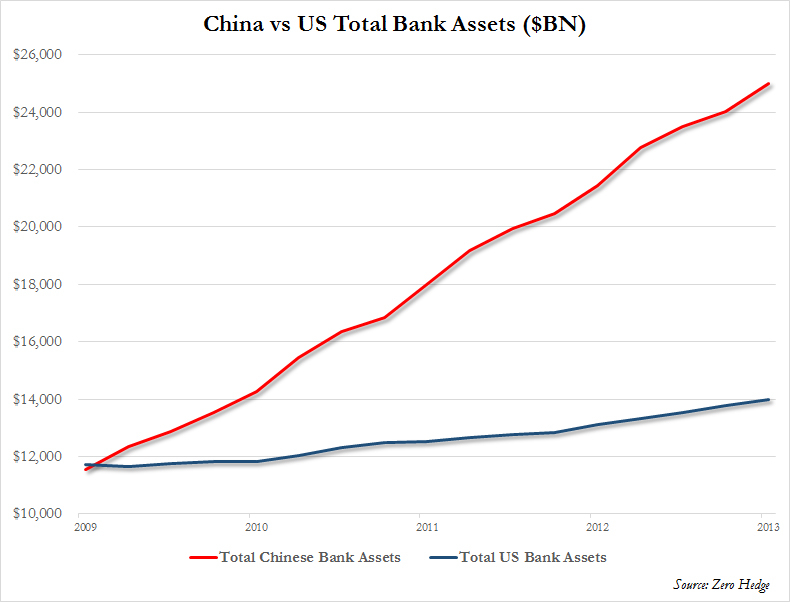

One of our favorite charts summarizing perfectly the Chinese credit bubble, better than any other, is the following which compares bank asset (i.e., loan) creation in China vs the US.

It goes without saying that while the blue line has troubles of its own (namely finding the proper rate of liquidity lubrication to keep over $600 trillion in derivatives from collapsing into an epic gross=net garbage heap), it is the red one, that of China, where $1 trillion in credit was created in the fourth quarter alone, that is clearly unsustainable for the simple reasons that i) China will quickly run out of encumbrable assets and ii) the bad, non-performing loan accumulation has hit an exponential phase, which incidentally is why Beijing is scrambling to slow down the “flow” from the current unprecedented pace of $3.5 trillion per year.

It is also because of this wanton and mindblowing capital misallocation (the de novo created debt goes not into profitable, cash flow generating ventures, but into fixed asset investments which create zero and potentially negative cash flow, due to China’s already epic overinvestment resulting in ghost cities, and building that fall down weeks after their erection) that China has finally decided to provide lenders with the other much needed component of the return equation: risk. This, in the form of debt defaults, something unheard of in China for two decades.

Which brings us to today, when we find that China’s credit formation, until now proceeding at a breakneck speed, has suddenly ground to a halt. Reuters explains:

Some of China’s struggling firms are finally getting the reception that regulators have been hoping for – a cold shoulder from banks in the form of smaller and costlier loans.

Reuters has contacted over 80 companies with elevated debt ratios or problems with overcapacity. Interviews with 15 that agreed to discuss their funding showed that more discriminate lending, long a missing ingredient of China’s economic transformation, has become a reality.

Up against a cooling Chinese economy and signs that authorities will not step in every time a loan goes bad, banks are becoming more hard-nosed and selective about whom they lend to.

…

For household goods maker Elec-Tech International Co Ltd (002005.SZ), less credit is the new reality. Its bank cut its borrowing limit by 500 million yuan ($80.79 million) to no more than 2.5 billion yuan this year, said Zhang, an official at Elec-Tech’s securities department.

“Last year, the bank gave us a discount on our interest rates. This year, we probably won’t get any discount,” Zhang who declined to give his full name said. “It feels like banks are not lending and their checks are becoming more rigorous.”

…

There are signs that even state-owned firms, in the past fawned over by lenders for their government connections, have to contend with higher rates, lower lending limits and more onerous checks by banks.

“Interest rates are going up 10 percent for the entire industry,” said Wang Lei, a finance department manager at PKU HealthCare Corp. “Obtaining loans is getting difficult and expensive.”

Here’s why PKU Healthcare will likely be among the first to experience what happens when the liquidity runs out:

PKU HealthCare, which is controlled by Peking University and makes bulk pharmaceuticals, has struggled to remain profitable. Its debt-to-EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization) ratio exceeded 60 at the end of September, four times the average for listed Chinese companies from the sector.

That’s the kind of leverage that not even Jefferies would sign a “highly confident letter” it can raise a B2/B- debt deal at 10% or less. It is also a huge problem for Chinese corporates which suddenly realize they have just a tad too much debt on their books.

Some gauges of China’s corporate debt are already flashing red. Non-financial firms’ debt jumped to 134 percent of China’s GDP in 2012 from 103 percent in 2007, according to Standard & Poor’s.

It predicted China’s corporate debt will reach “stratospheric levels” and become the world’s largest, overtaking the United States this year or next.

Fearing a wave of defaults as China’s economy cools after decades of rapid growth, regulators in the past two years told banks to cut off financing to sectors plagued by excess capacity such as steel and cement.

Experts say banks were at first slow to respond, but in the past few months, banks have started turning down credit taps.

“We have become more prudent in issuing loans,” said a spokesman for Bank of Ningbo. He added that the bank has intensified communication with companies in troubled sectors or borrowers deep in debt.

“Under normal circumstances, we would review company loans every quarter or every six months, but for the sensitive cases, we will step up channel checks and work closely with the companies.”

Another manager at a regional Chinese bank said it was overhauling its lending in cities identified as high-risk, such as Urdos and Wenzhou. Located in Inner Mongolia, Urdos is infamous for its clusters of empty apartment blocks that pessimists say is an emblem of China’s housing bubble. Wenzhou, is China’s entrepreneurial hotbed that recently lost its shine after local property boom went bust.

So with increasingly more uber-levered companies suddenly blacklisted by the banks, what do they do? Why go to the shadow banking system for last ditch liquidity of course, where it will cost them orders of magnitude more to stay viable for a few more weeks or months.

Ss companies bend the rules, risks shift outside the banking system into the universe of networks of seemingly unrelated firms connected by murky financial deals. For example, trade loans subsidized by the government to help selected sectors are quietly re-directed by companies to other unrelated businesses, firms say. New financing methods also emerge as easy credit dries up.

The latest plan hatched by a cash-strapped aluminum end-user involves having banks buy the metal and re-selling it to firms who pay out monthly loan plus interest.

How do you spell re-re-rehypothecation again… while selling the collateral…. again? Remember this: it really does explain all one needs to know about China.

“The local government has intervened, fearing social unrest. A local buyer of a unit in the office building committed suicide as he/she could not obtain the title to the property due to the title dispute between the trust and the developer.”

Anyway, continuing:

Others such as Xiamen C&D Inc, an import and export firm, are directly cashing in on firms’ thirst for funds. Xiamen C&D, which borrows at less than 6 percent per year is offering loans of several hundred thousand yuan to smaller firms at 7-8 percent, said Lin Mao, the secretary of Xiamen’s board of directors.

For larger companies, typical loans amount to 20-30 million yuan, and are 90 percent insured by Chinese insurers, he said.

Banks grow more aware of the risks. But rather than pull the plug on teetering firms, some bankers say they prefer a slow exit to keep them afloat for as long as possible to claw back their loans.

Unfortunately, for most the can kicking is now over. Which brings us to the second part of this story – China’s housing bubble, and specifically how its foundations – China’s own property developer firms – just imploded as a result of all the above. Also from Reuters:

China’s property developers are turning to commercial mortgage-backed securities and looking at other alternative financing as creditors grow more discriminating in the face of rising concerns about the country’s real estate and debt markets.

Bond buyers are shying away from second-tier developers because property sales have cooled as the economy slows. The expected bankruptcy of a local developer and the country’s first domestic bond default this month have heightened scrutiny of borrowers.

The property companies have a renewed sense of urgency to raise capital after U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Janet Yellen indicated the central bank, which sets the tone globally for borrowing costs, may raise interest rates as early as the spring of 2015, sooner than many investors had anticipated. Higher rates mean higher borrowing costs, both for the companies and for their home-buying customers.

Highlighting the search for alternative funding avenues, property fund MWREF Ltd earlier this month issued the first cross-border offering of commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) since 2006. The offer was priced at a yield lower than two dollar bonds issued last week, IFR, a Thomson Reuters publication, said.

“The market will see more of these products,” said Kim Eng Securities analyst Philip Tse in Hong Kong. “It’s getting harder to borrow with liquidity so tight in the bond market. It’s getting harder for smaller companies to issue high-yield bonds.”

The notes, issued through a MWREF subsidiary, Dynasty Property Investment, were ultimately backed by rental income from nine MWREF shopping malls in China and were structured to give offshore investors higher creditor status than is normally the case with foreign investors. MWREF is managed by Australian investment bank Macquarie Group Ltd, which declined to comment.

Beijing Capital was the first Hong Kong-listed developer to issue dollar senior perpetual capital securities last year, an equity-like security that does not dilute existing shareholders.

“As market liquidity is changing constantly, we have to keep adapting and exploring different funding channels,” said Bryan Feng, the head of investor relations.

Chinese regulators last week allowed developers Tianjin Tianbao Infrastructure Co. and Join.In Holding Co. to offer a private placement of shares, opening up a fund raising avenue that had been closed for nearly four years.

New rules were also unveiled last week allowing certain companies to issue preferred shares, including companies that use proceeds to acquire rivals.

“As liquidity tightens and developers see more pressure…they may consider M&A via preferred shares,” said Macquarie analyst David Ng.

CMBS, senior perpetuals, preferreds: what is the common theme? This is last ditch capital, far more dilutive of equity, and one which always appears just before the final can kick. As such, it means that the credit game in China is over. And now the only question is how long before the market realizes the jig is up.

Some already have. As we reported last week, “Cash-strapped Chinese are scrambling to sell their luxury homes in Hong Kong, and some are knocking up to a fifth off the price for a quick sale, as a liquidity crunch looms on the mainland.”

In other words, those who sense which way the wind is blowing have already entered liquidation mode. Because they know that those who sell first, sell best. Soon everyone else will follow in their shoes, unfortunately they will be selling into a bidless market.

Until then, we will greatly enjoy as finally, after many years of delays, the dominoes start falling.

As of March 15, Chinese developers had issued 15 U.S. dollar bonds raising $7.1 billion so far this year, compared with 23 issues that raised $8.1 billion in the year-earlier period. “That said, quite a number of developers have demonstrated the ability to access alternative markets, such as the offshore syndicated loan markets as another means of raising capital,” said Swee Ching Lim, Singapore-based credit analyst with Western Asset Management.

Offshore syndicated loans for Chinese developers have reached $1.17 billion so far in 2014, compared with $9.8 billion for all of last year, Thomson Reuters LPC data shows. Demonstrating the change in investor sentiment, bonds issued by Kaisa Group in January with a yield of 8.58 percent are now yielding 9.5 percent. The company did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Times Property issued a 5-year bond this month, not callable for 3 years, to yield 12.825 percent. A similar instrument from China Aoyuan Property in January was priced at 11.45 percent. Both Kaisa and Times are in the B-rating “junk” category, which is four notches above a default rating.

Property prices on the whole are still rising, but there are signs of stress in second and third tier cities. Early indications of property sales in March, traditionally a high season, were not promising, although final figures for the month would not be available until April, said Agnes Wong, property analyst with Nomura in Hong Kong. That may mean developers have to cut prices and investor sentiment may worsen.

“This is hurting the cash flows of the smaller players,” she said.

The market stresses ultimately could lead to the reshaping of the property development sector, said Kenneth Hoi, chief executive of Powerlong Real Estate Holdings Ltd (1238.HK), a mid-sized commercial developer.

“In the future, only the top 50 will be able to survive,” he said during a briefing on the company’s earnings on March 13. “Many small ones will exit from the market.”

The fun is about to start.