– Americans’ personal data shared with CIA, IRS, others in security probe (McClatchy, Nov 14, 2013):

WASHINGTON — U.S. agencies collected and shared the personal information of thousands of Americans in an attempt to root out untrustworthy federal workers that ended up scrutinizing people who had no direct ties to the U.S. government and simply had purchased certain books.

Federal officials gathered the information from the customer records of two men who were under criminal investigation for purportedly teaching people how to pass lie detector tests. The officials then distributed a list of 4,904 people – along with many of their Social Security numbers, addresses and professions – to nearly 30 federal agencies, including the Internal Revenue Service, the CIA, the National Security Agency and the Food and Drug Administration.

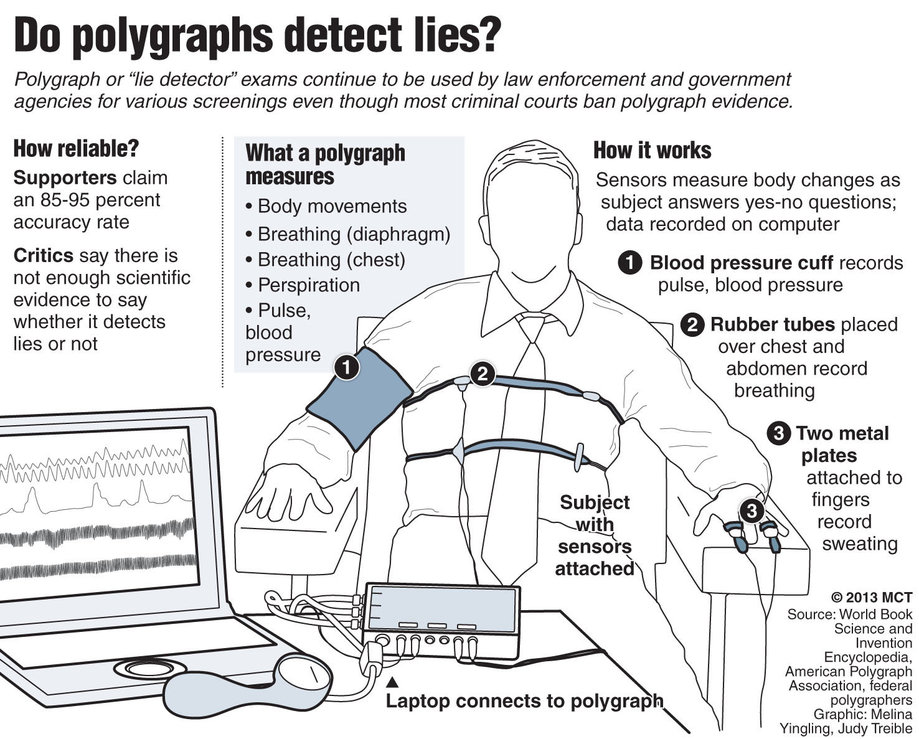

Although the polygraph-beating techniques are unproven, authorities hoped to find government employees or applicants who might have tried to use them to lie during the tests required for security clearances. Officials with multiple agencies confirmed that they’d checked the names in their databases and planned to retain the list in case any of those named take polygraphs for federal jobs or criminal investigations.

It turned out, however, that many people on the list worked outside the federal government and lived across the country. Among the people whose personal details were collected were nurses, firefighters, police officers and private attorneys, McClatchy learned. Also included: a psychologist, a cancer researcher and employees of Rite Aid, Paramount Pictures, the American Red Cross and Georgetown University.

Moreover, many of them had only bought books or DVDs from one of the men being investigated and didn’t receive the one-on-one training that investigators had suspected. In one case, a Washington lawyer was listed even though he’d never contacted the instructors. Dozens of others had wanted to pass a polygraph not for a job, but for a personal reason: The test was demanded by spouses who suspected infidelity.

The unprecedented creation of such a list and decision to disseminate it widely demonstrate the ease with which the federal government can collect and share Americans’ personal information, even when there’s no clear reason for doing so.

The case comes to light amid revelations that the NSA, in an effort to track foreign terrorists, has for years been stockpiling the data of the daily telephone and Internet communications of tens of millions of ordinary Americans. Though nowhere near as massive as the NSA programs, the polygraph inquiry is another example of the federal government’s vast appetite for Americans’ personal information and the sweeping legal authority it wields in the name of national security.

“This is increasingly happening – data is being collected by the federal government for one use and then being entirely repurposed for other uses and shared,” said Fred Cate, an Indiana University-Bloomington law professor who specializes in information privacy and national security. “Yet there is no constitutional protection for sharing data within the government.”

Several people who were on the list not only were stunned to learn about it, but they also questioned how the government could legally collect and share their information when they have no direct link to the inquiry. All of them said they were too nervous to be identified because they feared further scrutiny from the federal government or they didn’t want their names published by the media.

“When it comes to national security, the government has a lot of leeway,” said one Washington lawyer whose husband landed on the list after the lawyer bought a book about how to pass lie detector tests. “But to me, this list raises First Amendment, due process and privacy issues.”

The lawyer doesn’t work for the federal government. The husband is a government employee but isn’t required to take a lie detector test for a security clearance. “I’m concerned this may harm his career even though there’s no reason that it should,” said the lawyer, who added that they planned to ask the government to take the husband’s name off the list. “It’s very alarming and McCarthy-esque in its zeal. To put a person on a secret list because they bought the ‘wrong book’ or are associated with someone who did is overly paranoid.”

While the collection of the information likely passes constitutional muster, the federal agencies involved may have violated their own privacy policies by sharing the personal information of people who aren’t government employees, several legal experts agreed.

Some federal security officials also questioned how useful the list would be. Not only are the polygraph-beating techniques unproven, but confirming that they’ve been used is nearly impossible as well, scientists agree. In fact, the polygraph itself is deemed so unreliable that most courts don’t allow the results to be submitted as evidence against criminal suspects.

Federal agencies, however, are under increased pressure to detect security violators, also known as “insider threats,” ever since former NSA contractor Edward Snowden leaked documents earlier this year outlining the agency’s extensive collection of telephone and Internet data.

The Snowden case is only the latest in a series of what the government condemns as betrayals by “trusted insiders” who’ve harmed national security. As a result, the Obama administration has been pressing a government-wide crackdown on security threats that requires federal employees at agencies from the NSA to the CIA and the Peace Corps to the Department of Education to keep closer tabs on their co-workers and exhorts managers to punish those who fail to report suspicious behavior.

Officials say that one of the reasons for retaining the list of nearly 5,000 names is to help federal agencies detect future security violators, such as the next Snowden. It’s unclear how helpful such a list would be in that regard, though. Snowden underwent two polygraphs for his NSA job but he wasn’t found to have used polygraph-beating techniques to pass them, officials familiar with his tests told McClatchy. The NSA refused to comment.

Customs and Border Protection, the Department of Homeland Security agency that’s leading the polygraph investigation, has described it as important in rooting out crooked customs officials at the U.S.-Mexico border. Customs’ internal affairs division launched the polygraph inquiry after identifying 10 applicants who’d received the lie detector training from one of the instructors. Customs then assembled the list of customers’ names earlier this year as a result of court-approved search warrants that remain under seal in the criminal investigation, known as Operation Lie Busters.

Federal authorities acknowledge that the mere teaching of such techniques is protected by the First Amendment. However, prosecutors have pursued a novel legal theory in order to seek criminal charges. They assert that instructors who help federal applicants or employees try to hide lies during government polygraph tests are guilty of obstruction.

One of the Customs and Border Protection internal affairs officials involved in the case has urged authorities across the country to keep track of people who learn the techniques. The methods, known as countermeasures, include controlled breathing, muscle tensing, tongue biting and mental arithmetic.

“You have access to all of this data – all of their financial records, all of their telephone records, all of their transactions . . . ,” Customs official John Schwartz said in a June speech to police polygraphers that McClatchy attended. “Then we can look at that list and determine for ourselves if we are good or not good at detecting these countermeasures.”

Schwartz didn’t return calls about the case. Customs spokesman Michael Friel said that “since the matter is under investigation it would be inappropriate to comment at this time.”

In an email disseminating one version of the list in a spreadsheet, Defense Department official Frank Maietta asked polygraph managers at each agency to check the list for any federal workers or job applicants who might have gotten training.

The agencies included federal law enforcement and intelligence agencies such as the FBI and the Defense Intelligence Agency and others such as the Department of Energy and the Transportation Security Administration. McClatchy contacted the federal agencies that received the list from Schwartz and Maietta but most refused to respond to questions, citing the criminal investigation. Several, however, defended their overall adherence to privacy laws.

In the email to the agencies, Maietta, a polygraph official with the Defense Intelligence Agency, described the information as “merely a mailing list obtained from this case.”

“There’s no indication that any of these individuals did anything wrong, actually received hands-on training, took a polygraph anywhere, utilized countermeasures or are with any federal agency,” he wrote in the email in May.

Maietta said an earlier request for the same database check resulted in “very few” responses.

“Some of you indicated your agencies would not allow you to share information,” he wrote.

Nonetheless, the search eventually yielded dozens of federal applicants, several security officials with knowledge of the case told McClatchy. As fresh personnel information was gathered, officials updated the lists and circulated them across the government.

However, only a small percentage of the people on the list were employees with security clearances, said the officials, who asked to remain anonymous because of the sensitivity of the matter. They included one NSA contractor who feared revealing financial problems, a potentially career-ending admission.

Of the several hundred people who might have been linked to the Defense Department, however, a fraction underwent lie detector tests. Also, a portion of them hadn’t worked for the department since the 1980s.

“There was serious effort put into this list but it turned out to be a whole lot of nothing,” said one federal security official with knowledge of the overall effort who asked not to be named for fear of retaliation. “Only a handful of federal employees were directly involved.”

Sex offenders appeared on the list, including convicted child molesters who have to undergo post-conviction polygraph testing in some states, officials confirmed. But such offenders generally are monitored by state or local authorities, not the federal agencies that received the list. Federal prosecutors also don’t have the jurisdiction to seek charges related to those offenders.

Many, if not all, of the 4,904 names appear to be customers of an instructor who hasn’t been prosecuted and may never be. Federal agents collected the data in a search of Oklahoma instructor Doug Williams’ computers and business records. Williams, however, has said that he hasn’t committed a crime.

So far, one instructor has been prosecuted. Chad Dixon of Indiana began serving eight months in prison this month after pleading guilty earlier this year to obstruction charges, mainly as a result of an undercover sting. Dixon was recorded telling undercover agents that they shouldn’t tell federal officials about learning the techniques.

Despite Dixon’s criminal investigation, one of the numerous nurses on the list questioned why federal agencies would have a legitimate interest in her personal information.

“I’m not a federal employee. I’m a nurse,” she said. The 42-year-old woman declined to say why she’d sought the advice, but nurses are required to pass lie detector tests in some states for their licenses. “This does bother me,” she added about the effort. “My information was supposed to be confidential.”

The Supreme Court, however, has held that people who voluntarily turn over information to a “third party,” such as the polygraph instructors, would have no expectation of privacy under the Fourth Amendment.

“It doesn’t seem right to tar people and give them what is a scarlet letter of being likely liars just because they’ve been reading or thinking about beating lie detector tests,” said Lee Tien, a senior staff attorney with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a civil liberties group. “But the fact is government agencies have an enormous free zone when collecting and sharing data.”

Even so, it’s not clear under what circumstances various government agencies should continue retaining and sharing information about people whose only connection to the case was a book purchase.

“I think it’s a fair question to ask,” said Stephanie Pell, a former federal prosecutor with the Justice Department’s National Security Division. “What is the government’s rationale for continuing to retain and share the information once it is established that all someone did was buy a book?”

Others assert that the government clearly overreached. Customs officials recently confronted leaders of the agency’s union about their purchase of Williams’ book on beating lie detectors. Joseph Martin, the president of the Arizona chapter of the National Treasury Employees Union, said his vice president bought the book so the union could urge members not to voluntarily undergo a polygraph, because of its unreliability.

“What business is it of the government’s if we bought this book?” he said. “We have a right to read about lie detectors and tell our members not to take them.”

A customs internal affairs policy allows for the collection and sharing of records on federal applicants and employees, but it doesn’t appear to permit it when it involves people who have no federal government ties.

The Pentagon, however, said disclosures of personnel records for authorized law enforcement purposes were permitted, although it didn’t specifically address the issue of book-buying.

The FBI echoed that reasoning.

“The FBI routinely receives names of individuals from various law enforcement and criminal justice agencies to check previous criminal-history data or any other derogatory information that exists in our records,” bureau spokesman Paul Bresson said, adding, “After processing the names, we supply our results back to the submitting agency.”

The Air Force’s Office of Special Investigations checked the list “to only positively identify Air Force personnel,” spokeswoman Linda Card said. Defense Department policy “requires polygraph technical reports be maintained for a minimum of 35 years,” she said, without elaborating on whether the list could be kept that long.

The Pentagon’s inspector general, which also was involved in the database check, allows for the sharing of personal information of people who aren’t Defense Department employees “when their activities have directly threatened the functions, property or personnel of the Department of Defense.”

Washington attorney Kel McClanahan called that interpretation “quite a reach” in this instance, because people who buy books on beating lie detectors aren’t necessarily a threat. Still, suing the government would be an uphill battle because the Privacy Act of 1974 leaves so much wiggle room for agencies to collect and share personal data for law enforcement purposes, said McClanahan, who handles lawsuits alleging privacy violations.

“Even the most extreme cases of overreach like this are virtually impossible to litigate because of a poorly written law from 1974,” McClanahan said. “This is merely a symptom of the problem.”