– 10 Under-Reported Realities In The US Labor Market (ZeroHedge, May 29, 2013):

Beneath the unemployment rate and headline jobs number is a world of labor market signals that few, if any, ever take the time to look at. ConvergEx’s Nick Colas analyzes 10 under-reported signals to look for alternative clues about the direction of the job market and, in his words, the results aren’t pretty. We’re still 2 years away from full employment at the current pace of job growth, and more people are entering the labor force for the first time since the 1980s, adding to already fierce competition for open positions. Not to mention over 7% of those not in the labor force actually want a job right now (also intensifying competition), and the rate of job growth isn’t enough to offset the number of unemployed workers with expiring benefits. On the plus side, the number of re-entrants to the labor force is at a 4-year low. And for those who do have a job, average wages are higher than ever. However, the majority of the analysis shows the labor market remains stubbornly resistant to improvement – despite talking heads belief in ‘taper’ing on improvements.

Via Nick Colas of ConvergEx,

Note from Nick: We love “Top Ten lists.” Can’t get enough of them, really. Today Beth offers up one such collection, dedicated to the current state of the U.S. labor market. Looks like she could have had a “Top 17” or “top 22” list, but here are her best 10…

We’re kicking off summer with a deep dive into the BLS’s database of labor market statistics. We’ve been covering JOLTS in detail for quite some time, but felt some other lesser-discussed government jobs data deserved the spotlight as well. Below we’ve compiled a list of 10 under-reported clues as to the status of the labor market.

Yes, unemployment is falling and we’re seeing an improvement in monthly jobs numbers, but – as we explain below – there is much, much more to the story.

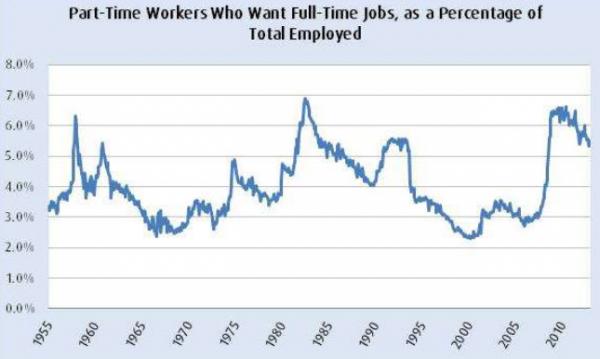

1) More than 1 in 20 part-time workers wish they had a full-time job. As of April, 5.5% of part-time workers were working sub-40 hour weeks because they were unable to find full-time work. The number of employees working part-time due to weak economic conditions hit a 25-year peak at 6.6% in March 2010, and while it has subsided since, there has been no material improvement in the past year – and it remains well above the long-run average of 4.0% (see chart following the text). This means that competition for available jobs is stronger than it appears. The current unemployment rate is 7.5%, but including those part-timers who are likely also searching for full-time employment, the unemployment rate would jump to 12.6%.

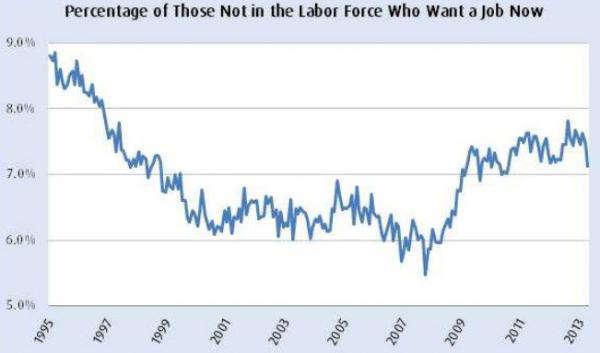

2) One in 14 of those who are not in the labor force actually want a job now. Last month 7.1% of people who were not in the labor force (i.e. not actively looking for work) said in a government survey that they wish to be currently employed. A majority of these people are discouraged workers who gave up hopes of finding a job and quit looking. In the years prior to the recession, the portion of people not in the labor force who indeed wanted a job, declined as more people who desired employment likely entered the labor force, where prospects were sunnier than today. The sort-of good news here is that, though this percentage hasn’t improved in the past year, it has flatted out somewhat (see chart). However it’s probable that as the labor market continues to improve, many of these people will reenter the labor force and buoy the unemployment rate.

3) The rate of job growth isn’t enough to offset the number of jobless workers with expiring unemployment benefits. Year-to-date through April, the number of people filing weekly continuing unemployment insurance claims dropped 759K. During the same time, the economy added 664K jobs, suggesting that 95K people who saw their benefits expire are still without a job.

4) As in other recent downturns, working men fared worse than working women during the financial crisis. This is a departure from the ’60s and ‘70s when the unemployment rate for women was structurally higher (see chart). The current unemployment rate for women is 7.3% versus 7.7% for men. During the worst of the recent recession only 9.0% of women were unemployed, compared with 11.2% of men.

5) Fewer people quit their jobs in April than in any other month since the end of last summer. According to the BLS’s count of job “losers” (no, we did not coin that term), 16.5% of those were due to job “leavers,” or those who voluntary gave up their position. This is the lowest percentage since the end of summer 2012 and nearly a third of the long-run average of 35.0% (see chart), indicating a slowdown in consumer and worker confidence – after all, who is going to quit their job without some basic level of faith in the labor market and in their own personal economic standing?

6) Peak numbers of new labor force entrants will continue to prevent faster improvement in the unemployment rate. In April 1.3 million people entered the labor force for the first time, comprising 10.9% of the country’s total number of unemployed people (see chart). In fact, the number of “Virgin” labor market entrants spiked in late 2008 and has exceeded 10% of the total unemployed population since January 2012. Most new entrants tend to be college graduates and former members of the military, meaning this trend is bad on 2 counts. First, it’s further evidence that recent college grads are struggling to find work, as employers tend to hire those with more skills (less of a gamble). And second, the government projects another 1 million people will transition out of military service by 2015, amplifying the labor force during a time when the economy is creeping ever so slowly towards a “normal” unemployment rate.

7) At the current pace of job growth, it will take us another 2 years to get back to full employment. The economy added 165K jobs in April and it would to do the same for the next 24 months in order for the unemployment rate to fall to 5%, which historically has been the Fed’s target. Of course, this is assuming the labor force doesn’t expand, which as we’ve briefly highlighted above, there is certainly room for expansion.

8) The typical unemployed worker has been out of work for 9 months. While the average number of weeks spent unemployed peaked at 40.7 at the end of 2011, the current average of 36.5 weeks isn’t even in proximity of the long-term average of 14.9 weeks (see chart). Additionally, the decline has been choppy, refusing to show consistent improvement. And note that the worst it ever got during other post-WWII downturns was an average of 20.5 weeks unemployed in 1983.

9) On a positive note, the number of reentrants to the labor force stands at a 4 year low. Last month, 3.2 million people rejoined the workforce, which was the least since April 2009. Historically, the number of labor force reentrants seems to indicate a weak economy (see chart), as people likely need to supplement family incomes during economic downturns (for example, stay-at-home moms who go back to work). The recent downtrend is a good signal because it not only suggests that fewer people need supplemental income, but also it means less competition for available jobs (fewer people in the workforce = less candidates for open positions).

10) And also on the bright side, for those who are currently working, earnings are higher than ever. Adjusted for inflation, the average worker earned $23.96 an hour in April, more than a buck higher than the year-ago month and $2 more than during the depths of the recession.

We concluded with 2 sort-of good signals, but the majority of our analysis shows the labor market remains stubbornly resistant to improvement. Monthly employment growth has firmed as of late, but with all those people still on the sidelines (discouraged workers, part-timers who wish to work full-time, etc.) we expect the unemployment rate to be sticky for quite some time.

There are plenty of people waiting to jump in, once they perceive an improvement in their labor market prospects, lending a case against all this speak of Fed tapering just yet.

Broken system, broken country, broken economy.