- Retention of unconvicted citizens’ samples criticised

- Home secretary promises report on how to comply

The judges said DNA profiles could be used to identify relationships which amounted to an interference with their right to respect for their private lives. Photograph: Science photo library

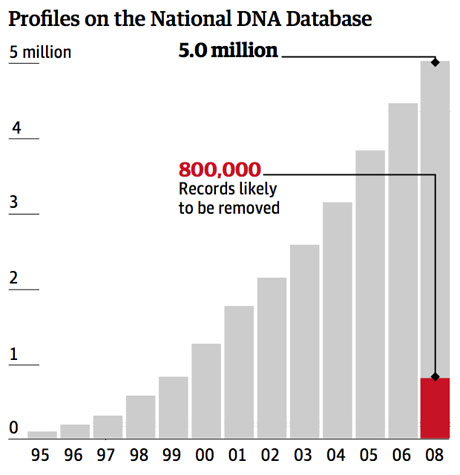

The fingerprints and DNA samples of more than 857,000 innocent citizens who have been arrested or charged but never convicted of a criminal offence now face deletion from the national DNA database after a landmark ruling by the European court of human rights in Strasbourg.

In one of their most strongly worded judgments in recent years, the unanimous ruling from the 17 judges, including a British judge, Nicolas Bratza, condemned the “blanket and indiscriminate” nature of the powers given to the police in England, Wales and Northern Ireland to retain the DNA samples and fingerprints of suspects who have been released or cleared.

The judges were highly critical of the fact that the DNA samples could be retained without time limit and regardless of the seriousness of the offence, or the age of the suspect.

The court said there was a particular risk that innocent people would be stigmatised because they were being treated in the same way as convicted criminals. The judges added that the fact DNA profiles could be used to identify family relationships between individuals, meant its indefinite retention also amounted to an interference with their right to respect for their private lives under the human rights convention.

The case provoked an expression of disappointment from the home secretary, Jacqui Smith, and the promise that a working party, including senior police officials, will report back to Strasbourg by next March on how the government will comply with the judgment.

“The government mounted a robust defence before the court and I strongly believe DNA and fingerprints play an invaluable role in fighting crime and bringing people to justice. The existing law will remain in place while we carefully consider the judgment.”

It is thought that the policy in Scotland, where DNA samples can only be held for a maximum of five years and only in serious violent and sexual cases, even if the suspect was not convicted, will be the first option to be looked at.

The Strasbourg court ruling came in a case brought by two Sheffield men who asked for their DNA records to be destroyed. The first man, Michael Marper, aged 45, was arrested in 2001 and charged with harassing his partner, but the case was dropped three months later after the couple were reconciled. He had no previous convictions.

In the second case, a 19-year-old named only in court as S was arrested and charged with attempted robbery in January 2001 when he was 12, but was cleared five months later.

Both asked the South Yorkshire police to remove and destroy their DNA samples and profiles and fingerprints. But police said they needed to retain them “to aid criminal investigation”.

Their lawyer, Peter Mahy, said last night: “This is a fantastic result after a seven-year hard fought battle against the UK government. We are obviously delighted that the European court of human rights found in our clients’ favour. It will be very interesting to see how the government respond – they should start immediately to destroy the DNA records of innocent people on the DNA database. ”

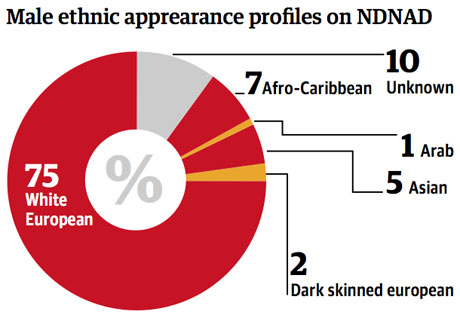

The ruling will have a major impact in shaping the future development of the DNA database in Britain and its use across Europe. Set up in 1995, the British DNA database which now holds the samples of 4.3 million individuals in Britain, including children, is already proportionately the largest in the world.

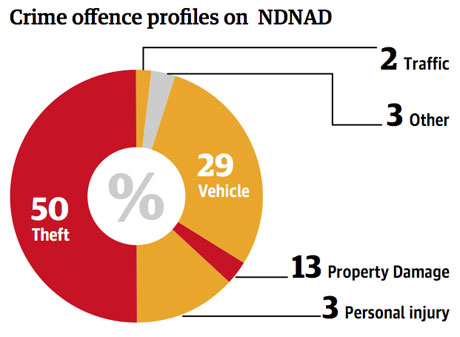

The Home Office acknowledged yesterday that its plans to extend the retention of DNA to low level, so-called non-recordable offences, including littering and minor traffic offences were now dead in the water.

Tony Bunyan of Statewatch, the European civil liberties monitoring group, also said it put a question mark over EU plans to share fingerprint and DNA data across the 27 member states.

The Association of Chief Police Officers said the ruling would have a profound impact on their use of DNA technology. They pointed out that over a four-year period from May 2001, 200,000 DNA samples taken from unconvicted suspects, had led to 8,500 individuals being linked with 14,000 offences including 114 murders and 116 rapes.

But Shami Chakrabarti, director of Liberty, said: “This is one of the most strongly worded judgments that Liberty has ever seen from the court of human rights. The court has used human rights principles and common sense to deliver the privacy protection of innocent people that the British government has shamefully failed to deliver.”

The Equality and Human Rights Commission said it welcomed the judgment and would work with the Home Office and the police to ensure the implications of the ruling were implemented.

Alan Travis, home affairs editor

Friday December 5 2008

Source: The Guardian