– An Unexpected $12 Trillion Hole Emerges In Donald Trump’s Plan To “Make America Great Again”:

The “great hope” that has lifted asset prices and inflation expectations over the past week, sent the Dow Jones and the Russell to all time highs, unleashed the highest US Dollar in 13 years and muted pundits who warned of a Trump-induced market crash is that the new president will soon unleash a “Reaganesque” fiscal stimulus, one which will unanchor inflation from recent stubbornly low levels, and succeed where the Fed and other central banks have failed since 2009. Adding to this speculation was Wednesday’s report that the Trump administration is even considering creating an “infrastructure bank” despite nixing the idea previously.

However, as we noted yesterday, there is one major difference between the days of Reagan and modern America: citing the Bond Vigilantes blog we noted that “when Reagan came into power, debt to GDP was just 30%. It is nearly 100% now, as such Reagan had much more fiscal headroom than Trump does today.” Echoing what we said one week earlier, the blog concluded that “if Donald Trump intends to flex the fiscal lever, bond market vigilantes could return with a vengeance, making it increasingly expensive for him to do so.”

Today the question of where the funding will come to sponsor Trump’s ambitious plan to “Make America Great” again and reform America’s tax code so that both the economy and inflation areshaken higher, is starting to emerge loud and center, and in an unexpected twist, a bit hurdle may have emerged. As Goldman writes in a research report overnight, strategist Alec Phillips writes that while “there is substantial support in Congress for proposals to cut taxes and reform the tax code and that there is likely to be sufficient support to enact a modest infrastructure package, perhaps combined with tax reform”, Goldman’s impression “is that market expectations of quick fiscal expansion may be running ahead of political and legislative realities.”

Goldman explains that tax reform has political momentum, which is likely to increase the budget deficit. “In light of the election result, we assume that the deficit will increase by more than previously expected. Specifically, we assume that fiscal policy choices under the next Congress will increase the budget deficit by around 0.75% of GDP, or around $150bn, in 2018, and similar amounts over the next few years.”

But here is the problem: Phillips explains that the market is more focused on fiscal “stimulus” than Congress is, which explains the blistering move higher over the past week. Trump proposes more expansionary fiscal policy—the Center for a Responsible Federal Budget estimates his plans would increase the deficit to $5.3 trillion over the next ten years. From the report:

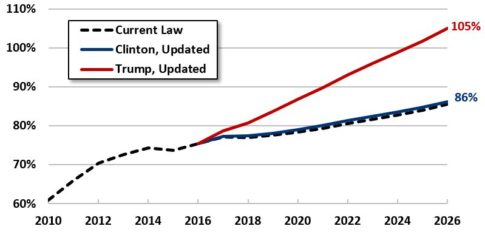

Incorporating rough and preliminary estimates of these new policies, we find that Clinton’s plans would increase the debt by $200 billion over a decade above current law levels (compared to our prior estimate of $250 billion), and Trump’s plans would increase the debt by $5.3 trillion (compared to our prior estimate of $11.5 trillion). As a result, debt would rise to above 86 percent of GDP under Clinton and 105 percent under Trump.

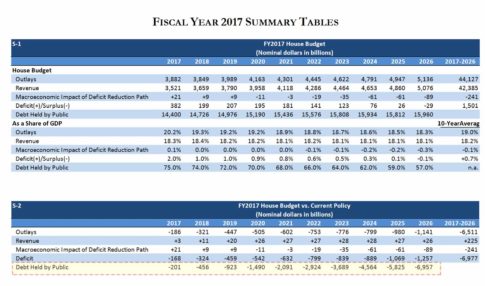

The problem emerges when one considers that the budget blueprint that the House approved earlier this year seeks to reduce the deficit versus current projections by $7 trillion over the next ten years, mainly through spending cuts.

And the punchline per the report: “These estimates imply the Trump fiscal plan and the House Republican fiscal plan are roughly $12 trillion apart over ten years, or a difference equal to more than one-quarter of total federal outlays.”

* * *

Then, there is the question of timing: Philips notes that markets are confident that major tax legislation will pass in 2017.

Part of the reason for this confidence is the ability to pass fiscal legislation (addressing tax policy, certain types of spending, and the debt limit) with a simple majority in both bodies of Congress, avoiding the possibility of filibuster and the 60 votes needed to overcome such procedural obstacles. With 52 Republicans in the Senate and 51 votes needed for passage (including the Vice President as tie-breaking vote if necessary), this allows for Republican-authored tax legislation to pass without Democratic support

However, there are drawbacks to using this approach. First, under congressional budget rules, legislation that is passed using the reconciliation process cannot increase the deficit after the ten-year period covered by the budget resolution. This means that if the tax reforms that Congress passes in 2017 increase the budget deficit, they would need to expire in 2028. Congress used this process to pass the 2001 tax cuts, which expired in 2012, resulting in the “fiscal cliff”. However, those tax cuts consisted largely of rate reductions that were somewhat simpler to reverse. Enacting major structural reforms to the tax code seems more difficult to do on a temporary basis.

Second, lawmakers may prefer to have bipartisan support, since tax reform will create winners and losers, and from a political perspective it could be better to share accountability for controversial decisions. This was a lesson of the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA, or “Obamacare”) using the reconciliation process; Republicans did not support the bill, and thus have a greater political incentive to repeal it than had it been a bipartisan effort. Ultimately, we expect congressional Republicans to keep open their option to use the reconciliation process to pass tax reform. However, even if they do, there is a chance they may seek bipartisan support, which could alter the size and composition of the tax reform package.

Which brings us to Goldman’s assessment of the practical limitations of Trump’s tax reform plan: “not everything on the agenda will happen, and little will happen quickly. Our expectation is that the major fiscal policy proposals that are being discussed will take the better part of 2017 to enact, and will probably not have significant economic effects until late 2017 or 2018.”

In other words, Trump’s overly ambitious plan may not only not pass, but will take over a year to see even modest implementation.

So where does that put us? Considering the market has rapidly priced in the full proposed benefit of Trump’s fiscal stimulus, two problems will emerge i) Congress will likely shoot down any budget that varies from the Republican baseline by $12 trilion over a decade, and ii) if the GOP does yield to Trump, the incremental amount of debt that will have to be issued and serviced will be mindboggling, and – coming at a time when foreign central banks are selling US Treasurys at a record pace – will likely require the Fed to step in and fund the deficit as Bernanke did with QE1 through 3, unless the scenario envisioned by Jeff Gundlach, in which bond yields soar to 6% in five years – resulting in the most acute stagflationary period in US history- materializes.

Of course, the market is a discounting mechanism and as such its job is to anticipate what the future holds (or at least it did that before central banks took over); however having already priced most of the best possible outcome, now that major questions are starting to emerge about not only the size of Trump’s economic plan, but also its timing, one wonders just how big of a disappointment may be in store for the market in the coming months as the full details of Trump’s plan, and its calendar, to make America great again slowly materialize.

* * *

PayPal: Donate in USD

PayPal: Donate in EUR

PayPal: Donate in GBP