– An Inside Look At Two “Unrelated” Banker Suicides Reveals A Fascinating Rabbit Hole:

It has been nearly four years since one of the most infamous, and still largely unexplained, banker “suicides” took place, the first in a series of many: we are talking about the death of the director of communications at Monte dei Paschi di Siena, David Rossi, who allegedly jumped to his death on March 6, 2013.

Since this event has largely faded away from the public consciousness here is a quick recap: David Rossi, who was the head of communications for Monte dei Paschi di Siena bank, which was founded in 1472 and which is currently seeking to finalize its third bailout since the financial crisis, died after falling – or being pushed – from a third floor window of the bank’s headquarters in a 14th century palazzo in the Tuscan city of Siena.

His death in March 2013 came at a time when the bank was pushed close to the brink of collapse over a scandal involving the loss of hundreds of millions of euros through risky investments.

While a quickly cobbled together post-mortem found that Rossi, 51, had killed himself, his family strongly suspected that he was murdered because he knew too much about the bank’s shady financial deals. As a result, earlier this year, prosecutors in Siena, where the bank is based, ordered his body to be exhumed and for the trajectory of his fall to be simulated, in an attempt to discover exactly how he died.

The death itself was suspicious: while Rossi fell, or was pushed, from his office at exactly 7:59:23 pm on March 6, 2013, and landed in a darkened alleyway, he did not die immediately – he was alive for 22 minutes, investigators believe.

What made Rossi’s death even more puzzling is that security camera footage, released years after his death, showed two shadowy figures appear at the end of the alley, apparently checking that there was no chance he would survive.

The scandalous video emerged in public this June, when the Post’s Michael Gray used it as the basis for an article asking “Why are so many bankers committing suicide?” For those who have not seen the 4 minute clip, we present it below in its entirety.

Among the oddities revealed at the site of the alleged suicide is that the executive had bruises and scratches on his arms and wrists which suggested that he may have been gripped forcibly by one or two assailants before being pushed out of the window. On the back of his head was a deep, L-shaped gash suggesting he may have been hit with a blunt object before falling from the window.

Three apparent suicide notes were found crumpled in a bin in his study, but Antonella Tognazzi, his widow, said they contained phrases that her husband would never have used. One of them said: “Ciao, Toni, my love. I’m sorry.”

“He never called me Toni, he always called me Antonella,” his widow, who has long contended that her husband did not kill himself but was murdered, said. The recent reopening

A handwriting expert who analyzed the notes said they seemed to have been written under duress. Another unexplained element is the fact that 33 minutes after Mr Rossi fell from his office window, a call was made on his mobile phone.

At exactly the same moment, the CCTV footage showed an object falling onto the ground and landing a few feet from the body; it was later found to be Mr Rossi’s watch, minus the strap.

To be sure, the recent emergence of the video has somehwat placated Rossi’s widow, Antonella Tognazzi, who got her wish for a re-examination into the circumstances surrounding Rossi’s death: “We’ve been waiting a long time for the investigation to be reopened,” said Ms Tognazzi early this year quoted by the Telegraph. “It’s what we had been hoping for – it’s an important sign on the part of the judiciary. I have never believed he committed suicide.”

The plot thickens when one digs into the details revealed by the footage captured on the surveillance video.

The footage shows the three-story fall didn’t kill Rossi instantly. For almost 20 minutes, the banker lay on the dimly lit cobblestones, occasionally moving an arm and leg. As he lay dying, two murky figures appear. Two men appear and one walks over to gaze at the banker. He offers no aid or comfort and doesn’t call for help before turning around and calmly walking out of the alley.

Two minutes into the clip, Gray also notes that “Italian authorities have yet to identify these two men.”

Following the Post article, there was a scramble by the Italian press to explain that the two men had indeed been identified, and to suggest that the local police knew, all along who they were. In a statement, the prosecutor of Siena said that the video on the fall of David Rossi “being circulated on the internet corresponds to the one already acquired during the investigation”. Moreover, the two men seen near Rossi’s body in the video footage were already interviewed in the first phase of the investigation.

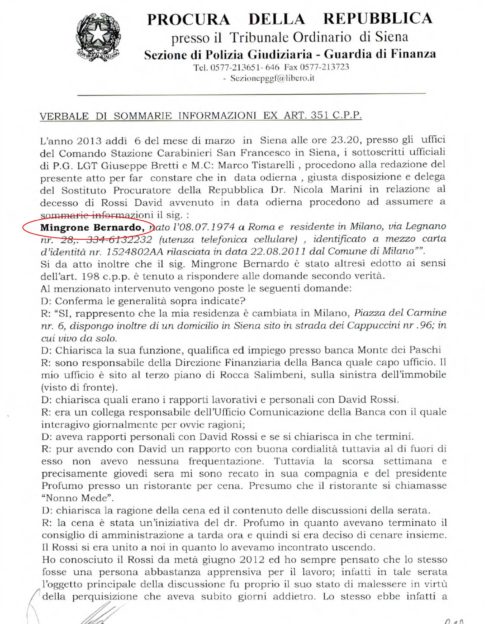

“For final confirmation and to avoid any further speculation, we have decided to re-interview the two men in the video as part of the new investigation,” wrote the prosecutor. The two people in question are Giancarlo Filippone and Bernardo Mingrone. “The first, seen wearing a padded jacket, was a colleague and friend of David Rossi, while Mingrone, who is wearing a coat and remains in the background, was at the time a senior executive in the MPS finance department.”

Courtesy of the police inquest into the suicide can confirm the two individuals seen in the back alley where Rossi died, were indeed his former coworkers Giancarlo Filippone a manager at Monte Paschi and a friend of Rossi, and Bernardo Mingrone, the CFO of Monte Paschi.

The police report notes the following testimony from Filippone, as recounted by Il Fatto Quotidiano: “I came from work at 18 and later I was contacted by the wife of Rossi who had not heard from her husband and begged me to go and call him. I sent him a text message at 19:41 (…) and got no response, so after waiting a bit I went to the office at 20:30 and when I entered the room I saw the window open, I looked below and saw David’s lifeless body.”

Mingrone’s testimony was also recorded: “At 20:40 on my way out I was talking on the phone, and just as I was in the hallway on the ground floor of the building heading towards the main exit, I met another man (Filippone) gesticulating dramatically and confused. The concierge mouthed the following words: “David Rossi” then “window”, then after hanging up the phone i met with Rossi’s colleague (Filippone, ed) who told me that David Rossi was thrown from the window. I asked the two where Rossi’s office was located and to accompany me there asking if they had called an ambulance. I entered the office and I looked out the window seeing the body on the ground; at that point I called 118 (emergency sevices) since I had been told that no one had called previously.”

That’s the official version; the actual video evidence demonstrates no panic, and no distressed among the two individuals, who calmly walk up to the dying body and then calmly walk away. The public prosector found little in the circumstances suspect, and as he detailed on June 17, there was no mystery as to the presence of the two men in the alley, where Rossi was either pushed or had jumped on his own.

Where some confusion does emerge, however, is that according to a different recount of events that night, Rossi did in fact speak to his wife Antonella whom he called at 19:02, one hour prior to the deadly fall, in which he did not speak as like someone who is going to commit suicide. To the contrary they were making dinner plans: “I will be home at 19.30. I already bought everything you need. But first I need to take the meatballs that I ordered for dinner. See you later.” He would never make it home as he was dead shortly after. Adding to the confusion is that after his death a number was typed on his cell: 409909 which, according to his lawyer, may have been a computer access code. It is unclear what was being accessed or who typed in the code.

But the question about the presence of the Monte Paschi CFO at the crime (or suicide) scene, is just one part of the mystery.

Two days prior to Rossi’s death, the communications director sent a cryptic

email to the bank’s CEO, Fabrizio Viola according to Rossi’s wife. “I want guarantees of not being overwhelmed by this thing,” he wrote. “We would have to do right away, before tomorrow. Can you help me?” As the post previously asked,”it remains a mystery what specifically Rossi thought could “overwhelm” him just before his death, but many have speculated that he was referring to Monte Paschi’s troubled financial position.”Incidentally, Fabrizio Viola stepped down as Monte Paschi CEO just one month ago, as the bank was deep in the middle of its latest, third, bailout process which however according to press reports has met substantial procedural hurdles and may not be completed, with speculation a debt for equity swap may be required to facilitate the bank’s rescue.

Furthermore, Rossi was a close confidant of former bank Chairman, Joseph Mussari, who was the driving force behind Monte Paschi’s 2008 $13 billion purchase of Banca Antonveneta from Spain’s Santander. Many banking analysts agreed at the time that Monte Paschi had overpaid for the acqusition, which incidentally was financed by Deutsche Bank.

Adding to the mystery, in October 2014, an Italian court sentenced Mussari to three years and six months in jail for misleading regulators in relation to a 2009 derivative trade with Nomura that prosecutors said was used to conceal losses. The court in Siena, where Italy’s third-biggest lender is based, also sentenced former chief executive Antonio Vigni and ex-finance boss Gianluca Baldassarri to the same jail term. Prosecutors had asked for a seven-year jail sentence for Mussari and six years for Vigni and Baldassarri.

Prosecutors had accused Mussari, Vigni and Baldassarri of hiding a document known as a mandate agreement, which prosecutors and regulators said made clear that the derivative, called Alexandria, was linked to the acquisition of 3 billion euros worth of long-term Italian government bonds by Monte dei Paschi. The link between the two trades meant they should have received different accounting treatment, which would have shown heavy losses. Alexandria and two other derivatives trades ultimately forced Monte Paschi to restate its accounts and book a loss of 730 million euros on its 2012 results.

New management at the bank, now working on a plan to fill the 2.1-billion-euro capital hole, has said it only discovered the existence of the mandate agreement when it was found in a safe in Vigni’s former office in October 2012, more than three years after it was signed.

If so far this all appears very confusing, is because it indeed is.

Where it gets even more confusing is that in January of this year, three executives from Deutsche Bank, which as we now know was very intimately involved with some of the illegal derivative transactions undertaken by Monte Pasci, were also implicated civilly, including Michele Faissola, the head of Private & Asset Wealth Management at Deutsche Bank— charged by Italian authorities with colluding with the troubled Monte Paschi in falsifying accounts, manipulating the market and obstructing justice.

Prosecutors have been reconstructing how Monte Paschi’s former managers misrepresented the lender’s finances in the years before it sought a government bailout. The misrepresentation first came to light in January 2013 when Bloomberg reported that Monte Paschi used a transaction with Deutsche Bank, the infamous Santorini (profiled here), to mask losses from an earlier derivative contract. The bank the same year had to restate its accounts

Faissola denied the charges.

Faissola, whose roles included overseeing rates and commodities, was put in charge of Deutsche Bank’s combined asset and wealth management division in 2012 when Anshu Jain and Juergen Fitschen took over as co-chief executive officers of the Frankfurt-based lender. Deutsche Bank on Oct. 18 said Faissola would leave after a transition period; his departure came just a few months after the sudden resignation of Co-CEOs Anshu Jain and Jurgen Fitschen in June 2015; it is said that Faissola was their close protege.

As a reminder, earlier this month, the recently troubled Deutsche Bank was itself charged by Italy for market manipulation and creating false accounts. Additionally, the name Faissole emerged once again, when as Bloomberg reported, six current and former managers of Deutsche Bank, including Michele Faissola, Michele Foresti and Ivor Dunbar, were charged in Milan for colluding to falsify the accounts of Italy’s third-biggest bank, Monte Paschi and manipulate the market.

Here is where things get interesting.

Michele Faissola was a coworker of one William S. Broeksmit. By way of background, Broeksmit had two stints at Frankfurt-based Deutsche Bank, first from 1996 to 2001, then from 2008 until his retirement in September 2013, having previously worked at Merrill Lynch. When he rejoined the bank in 2008 it was in a newly created position, head of portfolio risk optimization. In 2012, as Jain and Fitschen prepared to take over as CEOs, the duo advanced Broeksmit’s name to become the new chief risk officer. The bank retreated on his nomination after German financial regulator BaFin raised concerns that Broeksmit’s lack of experience managing a large number of employees.

Broeksmit worked as a consultant from his retriement until Janury 28, 2014… when the body of the 58 year old was found hanging in his London flat from a dog leash tied to the top of a door. He had just commited suicide..

As we reported at the time, financial papers had been strewn about the scene of his suicide, and on a dog bed near the body were a number of notes to family and friends. One was addressed to Deutsche Bank CEO Anshu Jain, with an apology. That note offered no clue as to the reason he was sorry.

And this is where the story gets even more fascinating: the abovementioned Michele Faissola, who was instrumental in helping Monte Paschi arrange its various derivative deals with Deutsche Bank, was the first to arrive at the gruesome scene of Broeksmit’s suicide in 2014.

When he arrived at the South Kensington home, he immediately began going through the bank papers and read the suicide notes.

We know all this because it was recounted to us by Val Broeksmit, the son of the deceased high-ranking Deutsche Bank banker. Val also who provided us the police report of David Rossi’s death, and various other key notes as he has tried to piece together over the years how and why his father committed suicide.

While there is no evidence Faissola was involved in any misconduct related to Broeksmit’s death, Val wonders what, if anything, Faissola had been searching for.

So do we.

The reason why this story, which has seen bits and pieces float around over the past 3 years, is reemerging is because now that both the insolvent Monte Paschi is in the news for its ongoing third bailout, not to mention the significantly troubled Deutsche Bank is also a daily source of market stress, the fact that two bankers who were intimately familiar and certainly involved in many of the transactions between Deutsche Bank and Monte Paschi, and which have been deemed illegal and are being prosecuted by the Italian state, have committed suicide, is worth bringing to the public’s attention.

* * *

What is fascinating, is not only how interconnected the fates of Deutsche Bank and Monte Paschi have been over the years – two banks that have each seen a dramatic, high ranking suicide in recent years – but also how far the political process has pushed to preserving a cone of silence surrounding these events: recall that on September 1, Milan prosecutors filed a request to shelve a probe for alleged market manipulation and false accounting against the chief executive of Monte Paschi, Fabrizio Viola, and the bank’s former chairman, Alesandro Profumo; a probe that was launched just several weeks prior. As noted above, Viola quietly resigned from his post shortly after the announcement.

Most importantly, while investigators on both the UK and Italian side have been quick to dismiss the banker deaths as open and shut cases of suicide, courtesy of Broeksmit’s son we have access to certain documents which we are confident will reveal not just how deep the rabbit hole truly goes, linking the oldest and biggest European banks through two still largely unexplained suicides, but also what is hidden behind Deutsche Bank’s mirrored facade.

PayPal: Donate in USD

PayPal: Donate in EUR

PayPal: Donate in GBP