– China Has A Massive Debt Problem … And Why It Is About Get Much Massiver (ZeroHedge, April 22, 2015):

We’ve spent quite a bit of time recently discussing the fact that China faces tough choices as Beijing attempts to counter decelerating economic growth while maintaining a peg to what has lately been one of the world’s strongest currencies. With pressure coming from four consecutive quarters of capital outflows totaling some $300 billion, devaluation is a somewhat risky (if inevitable) proposition and so the PBoC has opted for interest rate and RRR cuts to keep liquidity flowing into the economy.

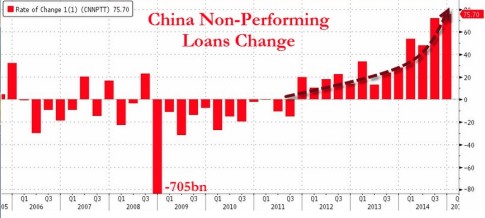

But even as the reserve requirement cut freed up more than a trillion yuan, policymakers must also grapple with competing agendas such as deleveraging a system that, as we exposed more than two years ago, and as Bloomberg now reports, is weighed down by a veritable mountain of debt.

China has a $28 trillion problem. That’s the country’s total government, corporate and household debt load as of mid-2014, according to McKinsey & Co. It’s equal to 282 percent of the country’s total annual economic output.

President Xi Jinping’s government aims to wind down that burden to more manageable levels by recapitalizing banks, overhauling local finances and removing implicit guarantees for corporate borrowing that once helped struggling companies. Those like Baoding Tianwei Group Co., a power-equipment maker that Tuesday became China’s first state-owned enterprise to default on domestic debt.

Now hold that thought, and consider this: China’s also trying to prop up a $10.4 trillion economy that’s decelerating and probably will continue to do so through 2016, or so says the International Monetary Fund. The economy expanded 7 percent — the leadership’s growth target for this year — in the first quarter, the weakest since 2009 and a far cry from the 10 percent average China managed from 1980 through 2012.

Against this backdrop, a barrage of recent policy moves out of China in recent days comes into sharper focus. It also helps explain why various parts of the government don’t always seem to be working from the same playbook.

“There’s obviously a contradiction between attempts to deleverage the economy and attempts to boost growth,” said Dariusz Kowalczyk, a senior economist at Credit Agricole SA in Hong Kong.

As a reminder, Baoding Tianwei Group Co (mentioned by Bloomberg above) is a subsidiary of state-owned China South Industries Group, and so when Baoding Tianwei indicated it would likely come up short on $14 million in interest payments due Tuesday, many speculated the parent company would step in to support it rather than risk a panic triggered by the first bankruptcy from a state-backed borrower. Instead, China South Industries called the issue none of their concern, suggesting that going forward, Beijing will allow the market to play a greater role in shaking out excessive debt burdens.

The country is also moving to curb the excessive margin debt that has helped fuel the country’s world-beating equity rally and is set to kick off a pilot program that will allow heavily indebted local governments to refinance their high interest loans (which total 35% of GDP) and save billions in interest expenses in the process (and which incidentally may eventually be part of the Chinese version of ECB LTROs). And that’s not all:

Among regulatory overhauls in train is a deposit-insurance program and ending a cap on deposit rates that effectively subsidized credit and punished savers. The deposit-rate ceiling may be abandoned this year and deposit insurance, a vital prerequisite, is scheduled to start May 1.

Putting depositor safeguards in place would allow for bank failures without stoking the kind of panic that spurred almost 1,000 customers to rush to outlets of Jiangsu Sheyang Rural Commercial Bank last year amid rumors the lender might go bust.

Moving toward a financial system where risk is more accurately priced and defaults tolerated is also crucial to the government’s fiscal overhaul of debt-besotted local governments…

All this explains why cleaning up the debt mess matters. With $3.73 trillion in foreign currency reserves, China has the financial resources to handle any future bank bailout or economic stimulus if need be.

Even so, if borrowing levels keep rising, at some point the country’s ability to both roll over existing credit and fund new projects will get tapped out. That’s not a good place to be for a one-party state with huge inequality and still-considerable development needs.

So in summary, China’s deleveraging efforts have the potential to work at cross purposes with Beijing’s desire to keep liquidity flowing and keep the economic machine from shifting further into low gear, but as Reuters notes, the PBoC is set to remove a bureaucratic hurdle from the ABS issuance process, which means that suddenly, trillions in loans which had previously sat idle on banks’ books, will now be sliced, packaged, and sold. This, in turn, will put in motion the classic securitization (non)virtuous circle in which banks offload credit risk to investors via ABS and, encouraged by the generation of securitization fees along the way, use their newly unencumbered balance sheet to make more loans to feed the securitization machine. This results, invariably, in shoddy underwriting as banks compete for business, and the amount of risk embedded in the financial system rises in lockstep with the percentage of securitizations backed by new loans to underqualified borrowers.

Here’s more from Reuters on the PBoC’s new rules for ABS issuance:

Issuance of Chinese asset-backed securities (ABS) could triple to more than $160 billion this year, reactivating huge assets now mouldering on bank books, as Beijing streamlines procedures for firms to securitise receivables.

By making it easier for banks to repackage and resell receivables – such as loan repayments on mortgages, car loans and credit cards – the government hopes to free up banks’ balance sheets so they can lend more to the real economy.

The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) announced this month that regulatory approval will no longer be required to issue ABS, and issuers will now only need to register to do so.

Getting banks to lend more is a major policy goal, given banks have so far been reluctant to lend despite repeated exhortations from top officials. Even Premier Li Keqiang has called for banks to “activate existing assets,” – which is where this securitisation push comes in…

Market players now expect ABS issuance to more than triple to 1 trillion yuan ($161 billion) this year, up from 300 billion yuan in 2014, which was in turn twice the total issued since 2005.

“There is a huge demand from banks alone to securitise assets,” said Zhao Hao, economist at ANZ in Shanghai.

“General demand can easily push issuance value exceeding 1 trillion yuan ($161 billion) this year.”

What this means is that China’s massive debt burden is about to get massiv-er, as banks use ABS issuance as a pressure valve to free up lending capacity. And as a reminder, here’s what will be going into the ABS collateral pools:

Until China becomes forthright and honest about their true growth, income and holdings, all of this is just more Chinese disinformation.

China is in trouble, far worse than their claims of a seven percent growth even begins to address. Ghost cities are but one example….. excessive government contracting forcing false expansion year over year is running into a brick wall. Without real growth generating from the real economy, it is just more debt expansion.