– The Death Of The Petrodollar Was Finally Noticed (ZeroHedge, Jan 7, 2015):

Three months ago, we wrote “How The Petrodollar Quietly Died, And Nobody Noticed[38]“, in which we explained in painful detail why far from the simple macroeconomic dogma which immediately prompted the macro tourists to scream that “oil prices dropping are good for US consumers“, the collapse in the price of crude is not only a disaster for oil exporting nations – one which will lead to a series of violent “Arab Springs” across the oil-producing developed world – but far more importantly, have a massive impact on capital markets as a result of the plunge in the most financialized commodity in history.

On the death of the Petrodollar we commented that unlike previously, when petrodollar recycling funneled the proceeds from oil-exports into financial markets, helping to boost asset prices and keep the cost of borrowing down, henceforth “oil producers will effectively import capital amounting to $7.6 billion.” We added that “oil exporters are now pulling liquidity out of financial markets rather than putting money in. That could result in higher borrowing costs for governments, companies, and ultimately, consumers as money becomes scarcer.”

The conclusion was simple: “net capital flows will be negative for EM, representing the first net inflow of capital (USD8bn) for the first time in eighteen years. This compares with USD60bn last year, which itself was down from USD248bn in 2012. At its peak, recycled EM petro dollars amounted to USD511bn back in 2006. The declines seen since 2006 not only reflect the changed global environment, but also the propensity of underlying exporters to begin investing the money domestically rather than save. The implications for financial markets liquidity – not to mention related downward pressure on US Treasury yields – is negative.”

In retrospect, it probably was not “simple enough”, because even three months ago everyone was confident that both higher yields and an increase in market liquidity are imminent. Since then not only has the yield on the 10 Year plunged to near record low levels (while 16% of global government debt now trades at negative yields), but judging by the absolute liquidity devastation in the E-Mini[39], in Trasurys [40]and virtually every other asset class, few actually grasped the implications of what plunging oil really means in a world in which this most financialized of commodities plays a massive role in both the global economy and capital markets, not to mention in geopolitics, with implications far, far greater than the amateurish “yes, but gas is now cheaper” retort.

So, three months later, we are happy to report that somebody finally noticed that the Petrodollar has indeed finally died, and more importantly, has attempted to put together an analysis of what we said in early November, reaching the conclusion that plunging oil just may not be all that financial comedy TV has it cracked up to be.

Did we say somebody? We meant everyone!

Below are extensive, in-depth, and long overdue questions on petrodollar recycling, or rather its halt, and its implications from virtually every single Bank of America economist and strategist who after months of stalling, have finally been forced to confront this most critical of topics head on.

From Bank of America

Q&A on petrodollar recycling

- We explore the economic, financial, and geopolitical implications that will result from the collapse in oil prices and the reduction in petro-dollar flows.

- We see a limited impact on UST yields or the USD. In recent years, the UK, Euro area and EEMEA have benefitted from reserve diversification away from the USD. A drying-out of petrodollar flows will reduce funding availability for current account deficit countries, particularly the UK, and may hurt London’s real estate sector.

- Venezuela’s debtors such as Cuba, which benefitted from Petrocaribe loans, as well as left-leaning regimes in LatAm, will feel the pressure. Russia could lose regional influence, although Ukraine’s dependence on its gas is still very high. Lower oil prices should diminish the ability of Iran to project regional power. Growth model limitations could eventually accentuate GCC social pressures, in our view.

The oil market outlook

Alberto Ades, co-head of Global Economics: Sabine, the natural starting point to a discussion of petrodollar recycling is an assessment of the oil market. What is your reading of OPEC’s policy shift?

Sabine Schels, commodity strategist: Before the recent oil rebound, Brent crude oil prices came off almost in a straight line from $115 to $50/bbl, making three very brief stops at $85, $80 and $60. That marks the second steepest six-month decline in the oil market’s history. In a dramatic policy shift, OPEC supply has kept increasing in recent quarters despite falling prices, as Saudi Arabia seems intent on increasing its market share, irrespective of the impact on price. Saudi Arabia has pledged not to take out supply even if the price drops to $40, $30 or even $20 per barrel, suggesting curtailments will have to come from high cost non-OPEC producers.

The sharp price decline is delivering a windfall-tax to consumers globally while giving a major blow to producers. For GCC alone, it is equivalent to $440bn in foregone revenues. In our view, OPEC’s decision to give up on its traditional role of keeping supply and demand in check will have far-reaching consequences across all asset classes as the flow of OPEC petrodollars is drying up. In the absence of a quick and sharp rebound in oil prices, this may drain liquidity from global asset markets, at least for the remainder of 2015.

Alberto Ades: Recently, you cut your oil price forecasts significantly. What drives your bearish view on oil prices for the next few months?

Sabine Schels: Basically, supply keeps running above demand. The term structure of Brent, which preceded the collapse in prices, continues to weaken across the next 12 months as inventories are building at an alarming speed, setting the stage for lower, not higher prices.

Inventories typically build because supply exceeds demand in any given market. But in some markets, like oil or gas, storage capacity is a finite number and price declines can accelerate as inventories build. In previous oil price downturns, OPEC would reduce supply as stocks built up to prevent a collapse in the term structure of prices. After all, when the price of storage soars, storage operators benefit and oil producers suffer

However, this new OPEC policy will likely create a large inventory overhang, suggesting further downside risks to oil prices. In fact, we see floating storage coming into play over the coming months with roughly 55 million barrels building on ships by the end of 2Q15 as land-based inventories across North America, Europe and Asia fill up. But even floating storage is limited by its very nature. If crude vessels fill up, shipping rates will spike; and that is unlikely to help any oil producer in the world.

Alberto Ades: Given this new OPEC policy, couldn’t non-OPEC producers simply turn off supply to stabilize prices? Are these producers large enough to influence the market significantly?

Sabine Schels: To restore equilibrium in the oil market, we would need a sizeable supply cut of at least 1 million b/d. In our view, it is not reasonable to expect non-cartelized production to shut down immediately as prices fall because many producers are well hedged, face very low cash costs, are partially protected by falling domestic currencies or tax breaks, or are notoriously slow to react. According to our estimates, with the exception of shale oil, which is cash flow intensive and thus dependent on price (current or forward), non-cartelized crude oil output in many parts of the world is not price sensitive at all, particularly in the first 12 months.

In the absence of a moderating agent like Saudi Arabia, this means prices have to fall below operating cash costs (non-shale) or well below cash flow breakevens (shale) for marginal producers. In our view, non-OPEC oil supply cuts will not come easy in the short run, as operating cash costs sit below $40/bbl. True, investments will be put on hold as some of the world’s output is challenged below $70/bbl in the long run. However, production guidance continues to point up in 2015 for most listed companies. Unless production guidance for 2015 goes negative or Saudi Arabia changes its policy, the market could become more disorderly as oil prices find a floor around operating cash costs.

As a result, we now expect oil prices to spiral down toward the end of 1Q and target Brent at $31/bbl and WTI at $32/bbl.

Alberto Ades: Since you expect no significant price bounce in the near future, do you see a risk of the flow of petrodollars drying up in the longer term?

Sabine Schels: We have argued that once spending cuts by non-OPEC producers, most likely US shale oil, are in place, Brent crude prices should start to recover. This will likely happen in the second half of this year, to a year-end target of $57/bbl. For 2016, we forecast Brent crude oil prices averaging $58/bbl. All else equal, this should increase the flow of petrodollars to the global economy, though to levels much lower than when oil was in the $100+/bbl environment. However, there is a risk to our base case. This assumption relies heavily on Saudi Arabian production staying at around the current level of 9.7 million b/d. While the kingdom pledges not to cut output to prevent prices from falling, this new OPEC policy could imply raising output, thus cutting into effective spare capacity. If this occurs, oil prices may stay low for longer, depressing the flow of petrodollars for years to come. This would allow them to increase their market share as oil prices recover, rather than allow shale producers in the US to reenter the market.

In this context, it is important to note that Saudi production is close to a record high in terms of total output, but not in terms of its share of the global market. So the question remains whether the Saudis want to put their spare capacity to work in coming years and increase output beyond 12 million b/d as oil prices start to recover. In that scenario, we estimate the fiscal budget breakeven price for the Kingdom would fall quickly, by $22/bbl from $94/bbl currently, meaning much-trumpeted reserves would last even longer to sustain this new policy.

Alberto Ades: Could a rebound in global economic activity support an oil price recovery, even under the new OPEC policy?

Sabine Schels: Our models suggest a six-month lag before lower prices start to impact consumption positively. Assuming the lower prices create no spiraling effect in emerging markets, this means global consumption should accelerate meaningfully in the second half of this year and into 2016.

Global oil demand is driven by net oil importing countries and large oil producers. Incrementally, we still expect China and India to deliver the bulk of the global consumption increase in 2015, although we do not expect China’s oil demand to grow nearly as fast as it did between 2004 and 2010, given domestic housing woes and an expensive currency.

While large importing countries like the US, China and India will likely see a bounce in consumption in 2015 and 2016, demand in oil-producing countries could be meaningfully slower next year as recession bites in Russia and lower oil prices negatively impact Middle East economies. After all, many oil producers had

their cake and ate it too for years as oil prices rose.As a result, we remain very concerned that slower demand from oil-producing countries could come back to haunt the market. We estimate 50% of the growth in demand in the last 10 years has come from oil-producing countries, a clear downside risk to prices, and the flow of petrodollars, from here.

GCC: a possible tectonic shift in petrodollar recycling

Alberto Ades: Jean-Michel, let’s turn to the regional impact of the petrodollar recycling dry-up for the countries in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). How did these countries recycle petrodollars during the oil boom years?

Jean-Michel Saliba, Middle East and North Africa economist: GCC oil export earnings totaled roughly US$1.04tn in 2014, for a cumulative US$10.8tn since 1970. These revenues have been recycled through two main channels, the absorption and financial account channels. The former refers to the use of oil export receipts to finance imports of goods and services. Through the second channel, current account surpluses translate into net financial investments in the rest of the world. The split in these flows comes from the sovereign’s intertemporal allocation decision between spending under the absorption channel and saving under the financial account channel. The latter also involves an asset allocation decision.

Alberto Ades: Let’s first discuss the absorption channel. How has it evolved since the 1970s?

Jean-Michel Saliba: GCC absorption capacity has increased steadily with the launch of large diversification and infrastructure spending programs. We estimate that around half of the GCC oil export earnings were spent and recycled through imports between 2003 and 2014. In comparison, during the oil boom of the 1970s and 1980s, the ratio of imports to exports increased rapidly from 0.3 to 0.6 on average in the 1980s and then remained fairly elevated on large domestic development plans and declining oil prices. After peaking at 0.8 in 1986, the ratio has declined gradually after the spending drop of the 1990s. This suggests the absorption channel has diminished in importance for GCC this time around.

Also, in the past, higher GCC imports lent support to global demand and mitigated the widening of DM current account deficits due to higher oil prices. In other words, imports were sourced back from developed markets. Over time, this channel has become somewhat USD-negative as trade links with the US decreased at the expense of the rise in the share of Asia.

Alberto Ades: Is it safe then to conclude that the financial account channel has recently gained importance for the GCC?

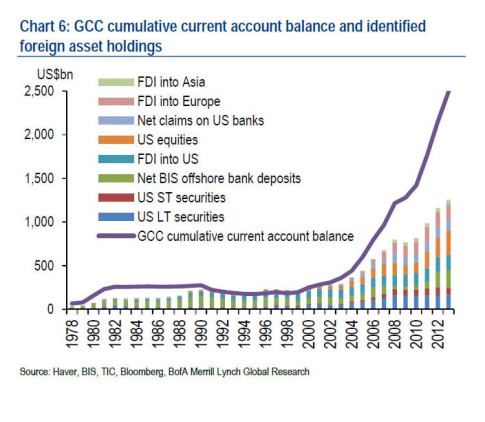

Jean-Michel Saliba: Yes, and this is probably the reason why this is the channel people tend to focus on when speaking of petrodollar recycling. Current account data suggest the GCC has accumulated $2.7tn in net foreign assets since the 1970s1, $2.4tn of which has likely come during the most recent oil boom that started in 2004

Saving GCC petrodollars in the form of foreign assets held abroad has occurred largely through the official sector. In turn, the GCC official sector’s outward investment has helped sterilize oil receipts. This has shielded the domestic economies from excessive or volatile liquidity, albeit only incompletely given the presence of currency pegs and robust fiscal expansion.

Over time, the role of the GCC monetary authorities, except for the Saudi Arabia Monetary Agency (SAMA), has been eclipsed by the rise of sovereign wealth funds. This likely implies a less risk-averse asset allocation by GCC.

Alberto Ades: You bring up an important new player, namely the SWFs. Their relative size and influence over global markets has increased sharply since the

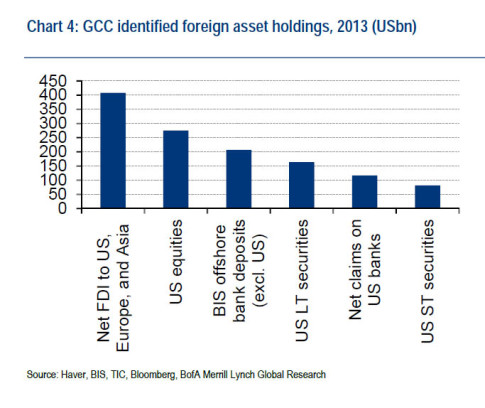

1980s. What are the implications of this?Jean-Michel Saliba: For one thing, the growing relevance of the financial account channel and the rise of SWFs have made it more difficult to track the flows accurately. Through our work, we have been able to account for the geographical destination of only about 50% of the accumulated GCC net foreign investment.

Previously, tracking was simpler because the bulk of financial flows passed through DM banks or DM securities markets. The GCC current account surpluses could broadly be explained by increases in FX reserves and bank deposits in the US and Bank of International Settlements (BIS) reporting countries. For example, between 1974 and 1979, 47% of total identified investments were deposited in bank accounts in developed economies or used to purchase UK or US money market instruments. The rest were simply used for long-term lending, mainly to developing economies through international banks. These patterns actually planted the seeds of the 1980s debt crises when flows dried out.

This time, financial account flows appear to have gained in sophistication, with diversification across a larger set of asset classes and geographies, including regional and domestic ones. This likely implies a potentially less risk averse asset allocation by the GCC countries

Alberto Ades: Of what you have been able to track, what are the geographical destinations of GCC petrodollar investment flows?

Jean-Michel Saliba: We believe the bulk of petrodollars recycled through the financial channel ended, either directly or indirectly, in the deep and liquid US financial markets. After all, the rise in the GCC current account surpluses was mirrored by the widening of the US current account deficit, whereas Emerging Asia has run surpluses and the Eurozone has kept relatively flat external balances. Therefore, these flows ended up financing the US, for the most part. Petrodollars may have funded an increase in domestic and regional investment on a relative basis as well, but this remains hard to quantify. That said, the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA) allocation could be used as a very rough guide on investment flows. Long-term neutral EM benchmark exposure for ADIA consists of between 15% and 25% of assets under management. This contrasts with 35-50% for North America, 20-35% for Europe and 10-20% for Developed Asia. Note that around 75% of ADIA’s assets are managed externally and some 55% of ADIA’s assets are invested in index-replicating strategies.

In terms of the cumulative stock of identified GCC foreign asset holdings, most of it is concentrated in foreign direct investments in Europe, Asia, and the US, BIS offshore bank deposits and US equities

Alberto Ades: What would be the main implications of the dry-up in petrodollar recycling likely to happen in a lower oil price environment?

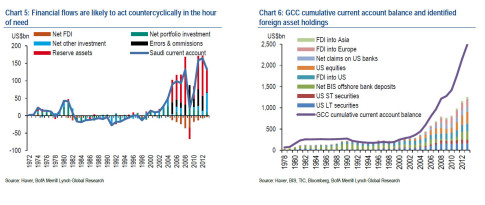

Jean-Michel Saliba: Lower oil prices for longer should imply material shifts in the size and direction of petrodollar recycling flows. Every $10/bbl drop in oil prices shaves off 4.2% of GDP from GCC current account balances. The move in oil prices between US$115/bbl and US$52/bbl would therefore shave off US$440bn in export revenues annually. The GCC external current account breakeven oil price is at approximately $65/bbl, which would only make the region a net external creditor if oil prices rebound sharply this year. The regional fiscal breakeven oil price is at $85/bbl, suggesting the GCC is set to run a fiscal deficit on aggregate, the bulk of which is likely to be financed through a drawdown of foreign assets currently held abroad.

History suggests GCC’s fiscal adjustment occurs with a lag. This would imply a sticky absorption channel through still elevated imports in the near term. During the first year or so of low oil prices, a country such as Saudi Arabia would draw down its official reserves to finance the balance of payments gap. These assets are most likely invested in foreign deposits and liquid US securities, which would take a hit. Later, financial account flows, which in the era of high oil prices were invested abroad to sterilize oil receipts, would likely reverse their direction. This would leave a more manageable drawdown of official central bank assets. Petrodollar shifts could reshape the geopolitical landscape

Alberto Ades: Jean-Michel, let’s conclude by discussing the changing geopolitics. What impact do you expect for the Middle Eastern conflicts?

Jean-Michel Saliba: Over a longer time frame, we would expect lower financial support to regional proxy armed groups to weaken some of the geopolitical dynamics on the ground. However, this can be moderated by various factors. First, in the local press, the Iranian leadership has expressed its belief that the new Saudi oil policy regime has clear geopolitical motives. The closest analogy is perhaps the 1985 Saudi oil policy regime shift, which sent oil prices tumbling and weighed on the conduct of the Iran-Iraq war. Iranian Foreign Minister Zarif recently suggested that lower oil prices diminish the possible gains of the Iranian regime concluding a nuclear deal with the P5+1 countries. Also, we note the Iranian macro adjustment could make the threat of further sanctions less potent.

Second, the resurgent Houthi military gains in Yemen, continued engagement in the Syrian conflict and recent Hezbollah-Israeli hostilities suggest Iranian regional ideological involvement is unlikely to alter course materially in the near term given the elevated stakes. In addition, a number of regional proxy armed groups were founded in the mid-1980s and appear to have developed alternative financing mechanisms.

Finally, in some instances, lower oil prices could accentuate sectarian conflicts in the Middle East. We suggested a risk to the colonial Sykes-Picot borders in Iraq, which has been addressed imperfectly through US external intervention and the recent budgetary agreement between Baghdad and the Kurdistan Regional Government. However, low oil prices challenge the economics of the deal and deepen Iraq’s fiscal strains and liquidity crunch.

Alberto Ades: Venezuela is another oil exporter that will also be directly impacted. Francisco, how did Venezuela recycle petrodollars during the previous oil boom? I get the sense that geopolitical trends in the region can’t be understood without a reference to Venezuela and the “grants” it distributed to countries with shared political affinities. Is this correct?

Francisco Rodríguez, Andean economist: Definitely. High oil prices in recent years allowed Venezuela to expand its influence in the region. The cost of this was very large for the country. We estimate the stock of loans to regional allies currently outstanding totals $25bn. This is larger than the current Venezuelan international reserves. In other words, the opportunity cost of Venezuelan foreign policy was not building a stabilization fund that would have enabled it to smooth out the adjustment during periods of declining oil prices.

These policies are unsustainable at current oil prices. In fact, the data already show a notable decline in trade credits and other public sector investment assets, two capital account items that essentially capture the change of liabilities of other countries with Venezuela generated as a result of Petrocaribe and other cooperation agreements. Net lending to other countries, as captured by the sum of these lines, fell to $1.9bn in the first three quarters of 2014 from $5.9bn and $11.2bn for comparable periods in 2013 and 2012, respectively.

Alberto Ades: And are we already seeing some of the effects of these drying out?

Francisco Rodríguez: Absolutely, the restoration of full diplomatic relations between the United States and Cuba is an important byproduct of this decline in Venezuela’s influence. From Cuba’s vantage point, the need to change its sources of external income is evident. As of 2013, it received oil shipments from Venezuela totaling 98mbd. In our view, the implications of this important announcement reach beyond Cuba’s borders, as it can help reshape the relationships between the US and Latin America, a region where a large fraction of governments is headed by leftist parties.

Alberto Ades: We cannot discuss geopolitics of oil without discussing Russia. Every day we hear that Russia will not only be affected economically but also politically, and even socially. Vladimir, overall, how important is oil for Russia?

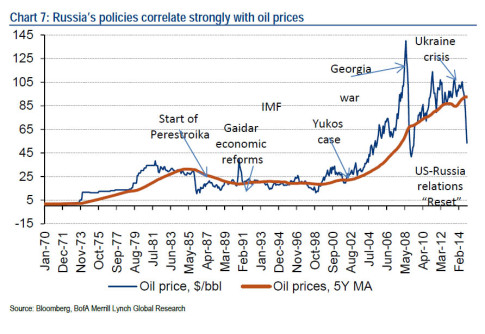

Vladimir Osakovskiy, Russia and CIS economist: We believe the impact of oil prices goes well beyond the economy and deeper into Russian society. This dependence goes all the way back to the late 1970s, when the then USSR became one of the major energy exporters and an important player on the global energy markets. In periods of relatively high oil prices, the abundant inflow of capital tended to create strong momentum in the economy, which also coincided with periods of a very assertive foreign and domestic policy

For example, historically high oil prices between the late 1970s and early 1980s correlated with the peak of the tensions between the US and the USSR in various parts of the world. More recently, record high oil prices in mid-2008 and between 2011 and early 2014 coincided with a brief war with Georgia in August 2008 and the political crisis in Ukraine. On the contrary, periods of low and falling oil prices have coincided with times when Russia’s relations with the West tended to improve. We can say that with respect to the entire Perestroika in 1987 and the US-Russia reset in early 2009.

Also, there are numerous ways in which such high oil revenues have been converted into political capital. Obviously, more abundant capital gave the government a greater ability to increase spending on such a political item as defense, which gave it more tools for an independent foreign policy on the international agenda. Russia’s defense spending reached peaks in the mid-1980s and in 2014.

Similar to what Francisco described for Venezuela, abundant and expansive energy resources also provide a lot of “soft power” that can be converted easily into political benefits through discounted gas shipments, direct financial support to loyal governments, etc. Over the past 5-10 years Russia has been quite active in supporting loyal governments in Belarus, Armenia and Ukraine. However, the capacity for such soft power is declining with lower oil prices and, even more importantly, the value of energy concessions that Russia can offer is falling as well.

Alberto Ades: Vadim, with all this background that Vladimir outlined, can we expect easing of the geopolitical tensions in Ukraine as a result?

Vadim Khramov, Ukraine and CEE economist: From the geopolitical standpoint, there is an argument that Russia would have to take a softer stance on Ukraine, as falling oil prices and western sanctions hurt the Russian economy. For now, the conflict in eastern Ukraine is still ongoing and at the end of 2014, there was even some escalation of tensions. Therefore, it is hard to say that Russia is taking a softer stance on Ukraine for now. However, we do not know the counterfactual on the situation had oil prices stayed high.

One major issue is related to Ukraine energy imports from Russia. As you know, Ukraine is an energy importer. According to our estimates, the recent drop in oil prices will allow it to save about $4bn on the imported gas bill as well as $3-4bn on petroleum-related imports. Also, Ukraine’s energy dependence on Russia has reduced not only in price but also in volume terms. This limits Russia’s ability to add more pressures on Ukraine.

That being said, our estimates show that Ukraine still will have to buy almost half of its gas imports from Russia in the next few years, as large gas substitution from Europe is unlikely. Therefore, even under a situation with low energy prices, Russia can add pressure on Ukraine along the energy lines. For this reason, in my view, the short-term impact of low energy prices on the Ukraine conflict overall is still limited.

Alberto Ades: Let’s briefly discuss potential impacts on domestic policies in Russia. Vladimir, are these affected as much as foreign policies?

Vladimir Osakovskiy: Sure. In the past, discussions about reforms in Russia have occurred during periods of low oil prices. For example, the USSR started democratization and its move away from the planned economy in the late 1980s when it was facing massive resource constraints due to a sharp decline in oil prices. After oil prices dipped below $10/bbl, Russia was pushed to accept the IMF program in 1998, even though it did not help to avert the default.

Conversely, the intensity of Russia’s reforms fell quickly and the government increased its assertive control over society as oil prices started to rise at the beginning of the century. The reformist and democratic agenda had a tentative recovery in 2009 when the oil price dropped below $30/bbl. However, this period faded quickly, just as oil prices recovered quickly.

* * *

Strategy impact will be larger for FX than for rates

Alberto Ades: Gustavo, let’s switch away from regional geopolitics and back into global economics and strategy. As petrodollar recycling dries out, will this hit global liquidity conditions?

Gustavo Reis, global economist: Jean-Michel noted petrodollar flows likely ended up in liquid US financial markets; therefore, a consequent effect would be diminished support for US asset prices. There are other adjustments that can override this, however. Unlike in the 1970s, when oil revenues were mostly recycled through banking channels, the ongoing adjustment in global rates and exchange rates is key to understanding how petrodollar flows will ultimately affect overall financial conditions.

Our Global Liquidity Tracker shows the recent oil price drop coincides with a moderate tightening in global liquidity conditions. The higher market volatility and diminished risk appetite have offset the drop in global bond yields. Much of this reflects global growth concerns, which have also been weighing on oil prices. Moreover, monetary policy in the Euro area and Japan will probably deviate from the playbook of looking through oil price changes by responding assertively to increased deflation risks.

Despite the uncertainty on recycling routes, my view is that petrodollar flows will be of second-order importance to global liquidity in 2015. Estimating the impact of petrodollar flows on global market conditions a decade ago, the International Monetary Fund found them to be limited. A more patient Federal Reserve, additional easing by the European Central Bank and Bank of Japan, as well as the decline in long-term global inflation expectations, will likely dominate. This suggests a contained potential impact of petrodollar flows over and above the market gyrations associated with the oil price plunge.

Alberto Ades: Shyam, in terms of strategy, given the GCC’s sizable holdings of US fixed income assets, what will be the impact on US rates? Should we expect a sell-off of US Treasuries?

Shyam Rajan, rates strategist: As Jean-Michel mentioned, there is definitely a risk that countries like Saudi Arabia will draw down liquid US securities to finance any balance of payments gap. After all, according to the latest TIC holdings data, OPEC nations hold about $280bn of UST, with another $200bn held by Russia and Norway.

However, we are less concerned about the impact of this flow on the rates market for two reasons. First, corporate bond and stock holdings of Middle East oil-exporting

nations have increased by almost twice that of UST over the last four years (up about $70bn since 2010). This increased preference for higher-yielding and higher-risk assets likely explains why the relationship between UST flows from this region and oil prices has weakened substantially recently. This is consistent with Jean-Michel’s intuition that the emergence of SWFs has probably led to a less risk averse allocation by GCC.Second, sales by these countries are usually more than offset by other flows. It is important to remember that the top four oil importers excluding the US (China, Japan, India and South Korea) own five times the amount of UST held by the oil exporters. Increased buying from these countries could therefore easily offset any sales. In addition, a further drop in oil prices as envisioned by Sabine would probably increase risk aversion and safe haven flows into the UST market.

Alberto Ades: Talk of UST yields and inflation may have implications for Fed action. Mike, could the shift in petrodollar recycling influence the Fed’s monetary policy during 2015?

Michael Hanson, United States economist: Not in my view. For the Fed, the decision on when to begin the tightening cycle will depend on how it assesses the progress toward maximum employment and price stability in the dual mandate. But as the January FOMC statement revealed, financial and international developments will also play a role. If the shedding of US assets by oil-exporting economies results in an appreciable tightening of US financial conditions, the Fed may move later or more gradually in its exit strategy.

* * *

In other words, from irrelevant, to “unambiguously good” if only for those who have zero understanding of what it means, suddenly the end of the Petrodollar recycling chain is said to impact everything from Russian geopolitics, to global capital market liquidity, to safe-haven demand for Treasurys, to social tensions in developing nations, to the Fed’s exit strategy.

Or said otherwise, we now know why the Fed felt like adding the word “international developments[45]” in its latest statement.

After combing through the entire article, the writer has some good points, but misses the obvious truth…..the dollar is dying and oil supply being kept high is dealing them a mortal blow.

Less than 30% of world nations now use the dollar to complete international transactions, it is becoming insignificant, and nothing can change it. Technology has rendered the need for any world reserve currency obsolete.

I wonder if and when they will state the truth.