Amid muni bond sell-off, bankruptcy talk deepens fears

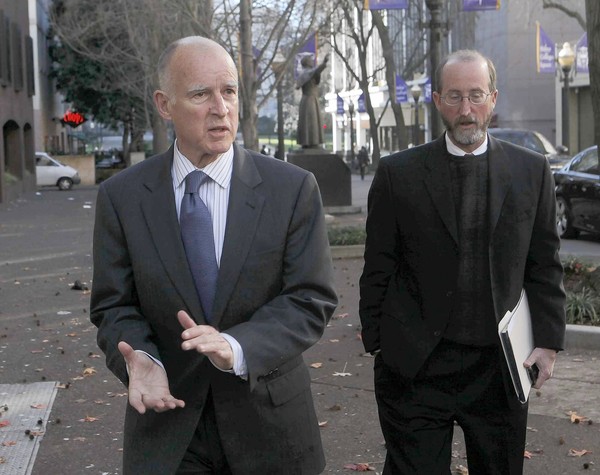

New California Gov. Jerry Brown, left, has proposed deep spending cuts and extending tax hikes to close the state’s budget gap.

Dateline Sacramento, Jan. 5, 2012: The state of California today filed for federal bankruptcy protection, citing a worsened economy that has blown out even the most pessimistic assumptions about its long-term financial picture.

Would that be a nightmare come true — or the only logical way out of the state’s deep fiscal crisis?

For now the question is purely academic because federal law doesn’t allow states to file for bankruptcy. But that could change if some conservative factions prevail in Washington.

There is a move afoot to persuade Congress to pass a law expressly permitting any of the 50 states to seek bankruptcy protection, a right that municipalities now have in about half the states.

Proponents of the idea say they’re doing California and other deficit-ridden states a huge favor. Given the severe budget shortfalls facing many governors and legislatures in 2011 and 2012 — and their massive unfunded employee pension and healthcare liabilities — the argument for bankruptcy is that it would allow a state to put everything on the table at once and plot a sustainable long-term financial recovery plan.

If it worked for General Motors, why not a state?

Among those backing the right of states to enter a formal bankruptcy is Americans for Tax Reform. Its director of state affairs, Patrick Gleason, doesn’t deny that the anti-tax group specifically wants to force the issue of pension and healthcare benefits to the forefront, which obviously would be a serious challenge to organized labor. But he says unions need to face up to the reality of state finances.

“It’s in their interest to renegotiate these contracts to something the states can afford,” Gleason said.

Some unions see a more sinister motive: crippling organized labor in its last great bastion, the public sector, where 37% of workers are union members compared with just over 7% of private-sector workers.

Chuck Loveless, director of legislation for the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, says the groups agitating for the state bankruptcy option are doing so “for the express purpose of reneging on collective-bargaining agreements.

“We take this very seriously,” he said. “They’re trying to create this hysterical atmosphere.”

Some proponents of a state bankruptcy option, including former House Speaker (and potential 2012 presidential candidate) Newt Gingrich, emphasize another motivation: They see the idea as a way for Congress to make clear to the states that they shouldn’t come looking for a federal bailout.

In a speech in November championing the concept, Gingrich specifically named California, New York and Illinois as states he feared would otherwise end up on Congress’ doorstep looking for more handouts.

The bankruptcy option for states still is in the realm of the hypothetical, but the rising debate already may be costing investors in the $2.9-trillion municipal bond market real money.

Lobbying efforts for a law making state bankruptcies possible are further eroding investor confidence amid what is already the worst sell-off in tax-free muni bonds since the financial-system meltdown in late 2008.

The market initially was slammed in November by a rise in interest rates on longer-term bonds in general and by a rush of new bond issuance by many states and municipalities.

More recently, muni prices have been hit by investors’ worries over worsening state and local government budget troubles and the risk that some borrowers could renege on their debts. And in particular the market has been terrorized by Wall Street banking analyst Meredith Whitney, who has been on national TV in recent weeks predicting a surge in muni bond defaults.

Whitney forecasts muni defaults totaling “hundreds of billions” of dollars in 2011. That has infuriated many muni bond market pros who insist that defaults will remain rarities.

As for municipal bankruptcy filings, they historically have been even rarer than defaults. (You can default on a debt without seeking bankruptcy protection.) Last year just six municipalities nationwide filed for Chapter 9 bankruptcy, the part of the federal code that applies to local governments, according to James Spiotto, a lawyer at Chapman & Cutler in Chicago and an authority on bankruptcy law.

With the muni market already so spooked, backers of the state bankruptcy option are giving investors another reason to stay away from the bonds.

If bankruptcy were made an alternative, “You could no longer assume that states would be immune from defaults,” said Matt Fabian, senior analyst at research firm Municipal Market Advisors in Westport, Conn.

Faced with even the slight possibility of a bankruptcy filing by a state — and therefore the risk that the terms of the state’s bonds could be renegotiated — investors would have to factor that into the interest rates they demand on munis. The result could be yields even above current levels that are now at two-year highs on many long-term issues.

Higher borrowing costs, of course, would be another blow to cash-strapped state and local governments.

“It would just wreak havoc,” Jeff Esser, chief executive of the Government Finance Officers Assn., said of the state-bankruptcy idea. His group’s 17,500 members are state and local finance officials.

For its part, California says the offer of a bankruptcy allowance is one it would absolutely reject.

Gov. Jerry Brown’s new budget plan, which proposes to slash the state’s deficit via deep spending cuts as well as the extension of recent tax hikes, is aimed at showing that California wants to “solve our problems on our own,” said H.D. Palmer, spokesman for the state’s finance department.

Illinois lawmakers, faced with a deficit equal to about half the state’s general fund revenue, this week did exactly what many Republicans are dead-set against: They raised the state’s income tax rate 66%.

Proponents of the state bankruptcy option doubt that the hardest-hit states can cope with the full extent of their financial challenges, particularly unfunded employee pension and healthcare promises, without the broad approach that a bankruptcy reorganization would allow.

“The issues are so big I really think they can’t be dealt with outside of bankruptcy,” said David Skeel, a University of Pennsylvania law professor. “What bankruptcy does is force the issues.”

But because states are sovereign entities, a central question is whether it would be constitutional for Congress to give them a bankruptcy alternative that would be overseen by a federal court.

Skeel insists that state bankruptcy could pass constitutional muster. The key, he says, is that it would have to follow the same rules that govern local-government bankruptcies: The decision to file would have to be voluntary (i.e., a state’s creditors couldn’t force it) and the bankruptcy court couldn’t interfere with governmental powers. “A court cannot force a bankrupt city to raise taxes or cut expenses, for instance,” Skeel said.

The effectiveness of a state bankruptcy filing, then, “would depend a great deal on the state’s willingness to play hardball with its creditors,” he said.

That is what will keep the muni bond market on edge if Congress takes up the state bankruptcy question.

Why? For many or most states, the long-term fiscal challenge isn’t bond debt. Rather, it’s promised pension and healthcare benefits that collectively run into the trillions of dollars. But in a state bankruptcy aimed primarily at forcing give-backs of employee benefits, organized labor surely would demand that bondholders, too, share the pain.

That could assure that any Chapter 9 filing by a state would be a drawn-out, politically ugly affair, not a fast-lane solution.

Chapman’s Spiotto argues that there’s no good reason for any government unit to seek bankruptcy protection except as a last resort. Historically, most governments have understood that, he notes: Since Chapter 9 bankruptcy was upheld as constitutional in 1937, just 620 government entities have used it.

Spiotto says the logical alternative to bankruptcy is to convene state or national commissions to decide, on a case-by-case basis, what is “affordable and sustainable” in terms of public-sector pension and healthcare benefits.

The severity of state and local financial woes may finally be focusing governments on the need to stop kicking that issue down the road, he said.

“If you can’t pay, you can’t pay,” he said.

By Tom Petruno Market Beat

January 15, 2011

Source: Los Angeles Times