While the country was embroiled in a national debate over excessive government surveillance in 1974, President Gerald Ford authorized the Federal Bureau of Investigation to conduct warrantless domestic surveillance, according to a classified memo recently obtained by the Center for Investigative Reporting.

The memo, signed Dec. 19, 1974, was issued just one month before the Senate established an 11-member panel, known as the Church Committee, to investigate government surveillance programs. The Church Committee would ultimately uncover other unconstitutional spying activities, such as that conducted by the National Security Agency under the rubric of Operation Shamrock. Two days after the memo was signed, investigative reporter Seymour Hersh, writing in The New York Times, disclosed a covert government spying program that focused on monitoring political activists in the U.S.

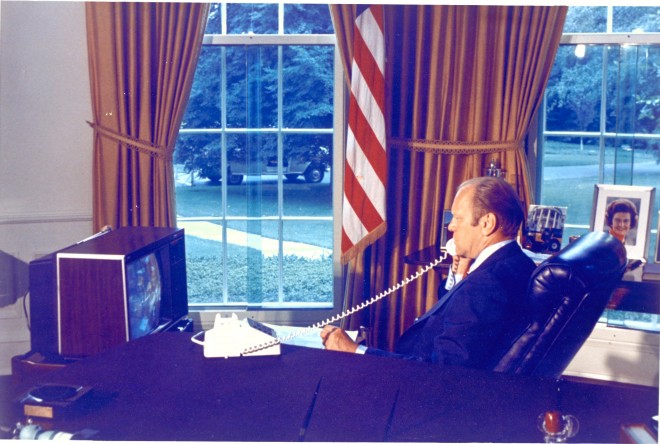

Ford became president after Richard Nixon’s resignation in the wake of the Watergate spying scandal, and he later supported passage of the pro-privacy Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978, which placed restrictions on wiretapping and required law enforcement to obtain permission from a special court to conduct domestic intelligence surveillance.

But according to the recently released top-secret memo, just two years earlier, Ford had secretly authorized Attorney General William B. Saxbe “to approve, without prior judicial warrants, specific electronic surveillance within the United States which may be requested by the Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation.”

Ford wrote in the memo to Saxbe that he had “been advised by you [Saxbe] and by the Department of State that such surveillance is consistent with the Constitution, laws and treaties of the United States.”

“This could be Bush after 9/11 or Obama after becoming president, but it’s President Ford 35 years ago, coping with Cold War struggles,” John Laprise, a visiting assistant professor at Northwestern University, told the center. “It’s really a stunning document that raises all sorts of questions.”

Ford’s order authorized surveillance for foreign intelligence and counterintelligence purposes, and would have involved spying on Americans or foreigners in the U. S. who were suspected of spying for foreign countries or foreign-based political groups. The open-ended surveillance authority could only be revoked by Ford or by order of a future president.

It’s not known to what extent the surveillance might have involved U.S. citizens or whether there was a specific incident or investigation that prompted the memo. In the memo, Ford writes that he “carefully reviewed the issues raised in your request for confirmation of authority and delegation with respect to warrantless electronic surveillance within the United States.”

The surveillance had to be in service of several objectives – to protect the United States against attacks by a foreign power, to obtain foreign intelligence that was deemed to be essential to national security, or to obtain information that the secretary of state or the national security adviser deemed necessary to foreign affairs.

Ford wrote that the warrantless surveillance would only be authorized with the personal approval of the attorney general “upon submission of a written request by the director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation providing complete justification for the conduct of such surveillance, including identification of the agency and presidential appointee initiating the request” and that only “the minimum physical intrusion necessary to obtain the information sought will be used.”

The National Archives obtained the memo, which it shared with the Center for Investigative Reporting, based in California. A previous, slightly redacted version of the memo was released in 2006.

A federal judge ruled last week that the George W. Bush administration violated the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act when the NSA eavesdropped on the telephone conversations of two American lawyers who represented a now-defunct Saudi charity.

Image: NASA/Kim Shiflett

By Kim Zetter

April 5, 2010 | 12:48 pm

Source: Wired