The banksters looting the American taxpayer again.

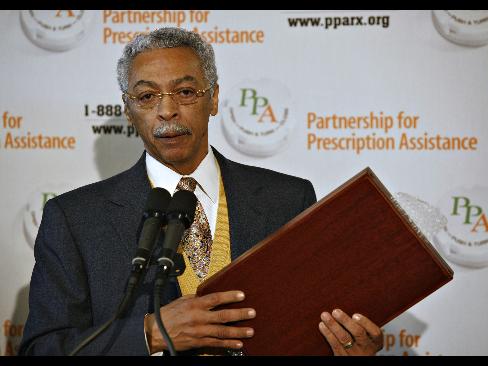

Larry Langford, then Jefferson County commissioner, speaks at a Partnership for Prescription Assistance event in Birmingham, Alabama, in this file photo taken Feb. 2, 2007. Photographer: Gary Tramontina/Bloomberg

Oct. 19 (Bloomberg) — In its 190-year history, Jefferson County, Alabama, has endured a cholera epidemic, a pounding in the Civil War, gunslingers, labor riots and terrorism by the Ku Klux Klan. Now this namesake of Thomas Jefferson, anchored by Birmingham, is staring at what one local politician calls financial “Armageddon.”

The spectacle — a tax struck down, about 1,000 county employees furloughed, a politician indicted over $3 billion in sewer debt that may lead to the largest municipal bankruptcy in history — has elbowed its way up the ladder of county lore.

“People want to kill somebody, but they don’t know who to shoot at,” says Russell Cunningham, past president of the Birmingham Regional Chamber of Commerce.

One target of their anger is Larry P. Langford, who was the county commission’s president in 2003 and 2004 and is now mayor of Birmingham. The 61-year-old Democrat goes on trial today, charged in a November 2008 federal indictment with taking cash, Rolex watches and designer clothes in exchange for helping to steer $7.1 million in fees to an Alabama investment banker as the county refinanced its sewer debt.

Jefferson County’s debacle is a parable for billions of dollars lost by state and local governments from Florida to California in transactions done behind closed doors. Selling debt without requiring competition made public officials vulnerable to bankers’ sales pitches, leaving taxpayers to foot the bill for borrowing gone awry.

Swaps Blew Up

Under Langford’s stewardship, the county bet on interest- rate swaps, agreements that a representative of New York-based JPMorgan Chase & Co. told commissioners could reduce their interest costs. Instead, the swaps — covering more than $5 billion in all — blew up during the credit crisis after ratings for the county’s bond insurers fell.

JPMorgan, through spokeswoman Christine Holevas, declined to comment for this story.

Thousands of public borrowers across the U.S. chose a similar strategy, and many are now paying billions of dollars to escape the contracts, said Peter Shapiro, managing director at Swap Financial Group in South Orange, New Jersey. Even Harvard University, the world’s richest academic institution with an endowment of $26 billion, fell for Wall Street’s financing in the dark: It paid $497.6 million to investment banks during the fiscal year ended June 30 because it chose to cancel $1.1 billion of interest-rate swaps.

Harvard Cuts Costs

The endowment fund lost more than $10 billion in value over the year, according to the school’s annual report. The Cambridge, Massachusetts-based university has frozen employee salaries, cut staff and offered other workers early retirement to cut costs.

Payments on Jefferson County’s debt, which switched from 95 percent fixed-rate financing to 93 percent variable-rate bonds hedged with swaps, eventually ballooned to $460 million a year, or more than twice the sewer system’s annual revenue.

Three of the five current commissioners are resisting voluntary bankruptcy. A filing would vault this county of 660,000 residents over Orange County, California, which lost $1.6 billion on derivatives in 1994 and ranks as the largest municipal insolvency to date.

Jefferson County’s collapse shows how people calling themselves financial engineers created borrowing schemes in the $2.8 trillion municipal-bond market that incorporated risk without the benefits of transparency. As state and local governments embraced floating-rate debt and interest-rate swaps, or agreements to exchange periodic interest payments with banks or insurers, they stopped requiring competition in bond sales.

No-Bid Sales

Less than 15 percent of $391 billion in new debt offerings were sold last year on the basis of public bidding — down from 83 percent of new sales in 1970. Most issues are now negotiated, meaning borrowing costs are set in private bargaining sessions.

In Jefferson County, the resulting opacity was a gateway to corruption, according to documents filed in Langford’s case. The Securities & Exchange Commission began probing the county’s swaps in 2004; the Federal Bureau of Investigation started inquiring later. In June 2007, SEC investigators deposed Langford in Miami about whether he used the sewer-debt refinancings to pay off political friends.

The public needs more transparency in municipal debt transactions, said Elizabeth Warren, chairwoman of the Congressional Oversight Panel for the Troubled Assets Relief Program. Proposed reforms, such as an oversight agency for consumer finance, can help spur improvements, she said.

‘Worldview Change’

“We need a worldview change about transparency and that includes municipal finance,” Warren said in an interview last week. “I believe the single biggest change a Consumer Finance Protection Agency would make is to give people financial products they understand and once that happens they’ll never go back. They’ll demand it in other areas, areas such as municipal finance.”

Investigators’ interest in Langford didn’t stop him from running for mayor of Birmingham in 2007. He leveraged a pro- business message with a vow to repave streets and clean up neighborhoods into an October victory over the incumbent and eight other challengers.

Thirteen months into his term, he was named in a 101-count indictment and led into federal district court in leg irons.

After Langford’s departure from the commission, its financial troubles deepened. A state court last January struck down an occupational tax that accounted for 25 percent of the county’s operating revenue, setting the stage for massive service cuts.

‘Gatling Gun’

Langford, meanwhile, has been running the city with a style that Tom Scarritt, editor of the Birmingham News, once characterized as a “Gatling gun of ideas.”

The mayor was gathering applause on July 21, the day his former colleagues on the commission gave notice that they might lay off up to one-third of the county’s 3,600-person workforce. The move presaged shutting satellite courthouses, putting a hospital for the poor in jeopardy and slowing to a crawl such services as auto-tag renewals.

That day, Langford stepped into the cab of a bulldozer at a groundbreaking ceremony for a $550 million, 57,000-seat domed stadium, the culmination of weeks of jawboning as he guided the project’s first $8 million in appropriations through the city council.

“Let me tell you something: We can do anything in this city we want to do,” said Langford, who worked as one of the region’s first black television news reporters in the 1970s before he got into politics.

‘In a Heartbeat’

Friends and foes say his political stock remains strong in Birmingham. He would “win in a heartbeat” if an election were called tomorrow, says Patricia Todd, a Democratic state legislator whose district lies partly in the city of 229,000.

In Jefferson County’s bedroom communities, some are seething over Langford’s role in the sewer-bond crisis and the county’s financial woes.

“He’s a pure idiot,” says David King, a pharmacist from Vestavia Hills, a town of 25,000 about six miles south of Birmingham.

The mayor’s trial was moved 47 miles away to Tuscaloosa from Birmingham after his lawyer argued that negative publicity had tainted the local jury pool.

In July and August, Langford’s two co-defendants pleaded guilty and agreed to testify for the prosecution. William B. Blount, a Montgomery investment banker and former chairman of the state Democratic party, and Albert W. LaPierre, a Birmingham lobbyist, admitted to taking part in a scheme to bribe Langford to get bond and interest-rate swaps business.

‘Political Witch Hunt’

Unbowed, the bespectacled, mustachioed Langford, known for tailored suits, oratorical flourishes and frequent evocations of his Christian religion, has declared his innocence, denouncing the charges against him as “a political witch hunt.” He declined to be interviewed for this story, citing a judge’s gag order.

While some on his staff initially were concerned the legal troubles might distract the mayor, they have motivated him, says Deborah Vance, his chief of staff. “Larry feels wronged — wronged,” she says.

If Jefferson County declares bankruptcy, it probably won’t move the bond market much because it’s been anticipated, says Richard A. Ciccarone, director of research at McDonnell Investment Management, an Oak Brook, Illinois, firm with about $12 billion under management.

Not Safe

The county’s story shows what can happen when creative financing meets old-school thinking, he says.

“You always hear that sewer and water-service bonds are safe,” Ciccarone said. “This is a good example of how that’s just not true.”

The county revealed in July that it had defaulted on $46 million of accelerated principal. It might already be in Chapter 9, the federal bankruptcy option for cash-strapped municipalities, except that it has received agreements from JPMorgan and other banks to hold off on forcing it to make accelerated payments on more than $800 million of unwanted bonds.

In August and September, amid the cuts that stemmed from the occupational-tax judgment, Jefferson County residents got a taste of what bankruptcy might look like. As the county began putting about 1,000 workers on leave without pay, one disgruntled employee allegedly e-mailed bomb threats to officials and was promptly arrested, according to the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Office.

Lines Form

Lines soon formed outside the courthouse as such tasks as renewing driver’s licenses slowed.

A kind of legal civil war broke out when three county agencies, the sheriff’s department, an indigent-care hospital and the tax-assessor’s office, sued the county commission to stop the budget cuts on the grounds that they posed a danger to public safety.

Bettye Fine Collins, the commission president, declared the situation, “our Armageddon.”

The fight over the occupational tax, a 0.50 percent levy on personal income, dates to 1999 when state lawmakers repealed it. The county appealed that action and won a series of state court decisions until January when a judge ruled the repeal was legal.

That left county leaders to find $75 million in cuts while they took the case to the Alabama Supreme Court, which upheld the lower court’s ruling in August. In parallel action, the state legislature reauthorized a modified version of the tax at a lower rate, 0.45 percent.

Workers Reinstated

Commissioners reinstated the furloughed workers this month, putting most on 32-hour work weeks. They have also sought a $25 million line of credit from Birmingham-based Regions Financial Corp.

The legislature may have saved the county from uncharted territory. With the occupational tax crunch and the sewer-debt crisis, Collins said she had feared that, “In the worst-case scenario we could be drawn into bankruptcy on both sides.”

In August, Bank of New York Mellon Corp., as trustee for owners of about $3 billion in sewer warrants, filed suit in Jefferson County Circuit Court seeking an appointed receiver for the sewer system. The receiver should have authority to raise rates enough to meet the debt service, the bank said in the complaint, which is pending. A federal judge turned down a similar request in June, saying he lacked jurisdiction.

The sewer system is already charging customers about 300 percent more to drain bathtubs or flush toilets than a dozen years ago.

Above National Average

By one county estimate, average annual bills are now about $750, compared with the national average of $331, according to a 2007 survey by the Washington, D.C.-based National Association of Clean Water Agencies, a coalition of utilities.

It’s impossible to boost them enough without putting them beyond the means of many residents, County Commissioner Jim Carns says. “We’re like a guy making $50,000 a year with a $1 million mortgage.”

Carns and Commissioner Bobby Humphryes, both Republicans, say they reluctantly favor bankruptcy, in part to prevent the appointment of a receiver who might seek increases. “We need a cram-down on the debt,” says Carns, adding that the county can afford to service less than half the obligations, about $1.4 billion worth. A bankruptcy court would have authority to reduce the amount owed.

Democrat Shelia Smoot, along with Democrat William Bell and commission President Collins, opposes filing voluntarily.

Detrimental for 50 Years

“It would be detrimental to our community for the next 50 years,” she says.

Orange County, after its 1994 default, was forced to take on “a crushing load of long-term debt,” according to a post- mortem published four years later by the Public Policy Institute of California, a nonprofit San Francisco-based economic research organization.

The county’s borrowing costs increased, forcing it to “divert tax funds from other county agencies (e.g. transportation) so the county government could borrow money to pay bondholders and vendors,” according to the report. The poor were hurt in particular. “Their services were cut during the bankruptcy and have not been fully restored.”

Langford, who rose from public housing in Birmingham’s Titusville neighborhood to its mayor’s office, is at the eye of Jefferson County’s storm.

After earning a bachelor’s degree from the University of Alabama at Birmingham in 1972, he served in the Air Force. Upon returning to the city, he began his TV news career, specializing in investigative pieces, according to a biography posted on his mayoral Web site.

Political Career Begins

His political career began in 1977, when he won a Birmingham City Council post. In 1988, he was elected mayor of Fairfield, a suburb of 11,300 about nine miles southwest of the county seat. He studied at the Harvard University Kennedy School of Government during 2000 and in 2002 ran for the county commission.

His October 2007 Birmingham mayoral victory was powered largely by his popularity among the city’s 74 percent black majority. Once elected with 50.3 percent of the vote, “he had a lot of white corporate leaders who were quickly at his side currying his support,” says Robert G. Corley, a Birmingham native and director of UAB’s Global and Community Leadership Honors Program. “And in many ways he’s delivered on key projects that they wanted.”

Launching Projects

The mayor immediately launched “23/23,” which guarantees cleanup crews will scour the city’s 23 neighborhoods every 23 days.

He embarked on a three-year project that will spend as much as $48 million toward a goal of repaving all 1,100 miles of Birmingham’s streets.

Langford also persuaded the council to appropriate $20 million for expanding Birmingham’s Children’s Hospital, and $1 million toward renovating Bethel Baptist Church, the headquarters of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights during the Civil Rights era. He was instrumental in renaming Birmingham International Airport for Fred Shuttlesworth, the church’s leader during the 1960s, Vance said.

Two other Langford projects are scheduled to be completed next year. A $7.5 million hall of fame is planned to honor baseball players from the Negro and Southern Association leagues during the Jim Crow period, and a $1 million Civil Rights and Heritage Trail will document scenes of local struggles.

“Under my leadership, the city, with its ‘do something’ attitude is determined to be the best ‘New South’ city in the nation and one of the world’s leading centers for medical research, biotechnology, green space and world-class culture!” Langford’s Web site says.

‘Make Things Happen’

“This mayor is very eager to accomplish things, do things, make things happen,” says Michael Calvert, director of Operation New Birmingham, a business group that pushes for downtown development.

His tactics can range from cajolery to confrontation. The dome, a planned stadium for which Langford has not yet announced any professional sports tenant, provides an example.

First proposed more than a decade ago, the project lay dormant until he revived it as central to his administration, saying Birmingham’s current convention center isn’t big enough to draw major sporting events or mega-conventions that could boost city commerce.

When approval stalled amid a budget wrangle in July, the mayor told council members he wanted them to watch a promotional video.

One Small Step

Down went the lights in the council’s paneled chambers and up on overhead screens came the pitch — without a word about the dome’s virtues. Instead, 90 seconds of flickering footage of the July 1969 moon landing appeared over the words: “It took less time to go to the moon than it’s taking us to build the dome.”

The audience laughed, yet the council still balked at the funding. One member noted that the progress and financing report Langford presented for approval was stamped “draft” by the city attorney’s office.

That was an error, the mayor’s office said after the meeting. Later that afternoon, Langford fired the city attorney responsible. Vance confirmed the dismissal.

“He can be very charismatic and he can be very intimidating,” says UAB’s Corley.

Langford has stayed out of the county’s occupational-tax controversy except to suggest that commissioners enact an across-the-board pay cut instead of putting large numbers of employees on unpaid leave. His advice was ignored.

‘Kind of a Joke’

“I think it’s kind of a joke that Mr. Langford says he now has all these solutions for us when he’s the one who helped us get in this problem,” says Linda Sexton, a 25-year-veteran of the county’s sewer department.

Alabama is no stranger to political turmoil and corruption. In the 1990s, Guy Hunt, a Republican governor, was removed from office after being convicted on an ethics violation involving the misuse of inaugural funds. Hunt was eventually pardoned.

In 2006, Richard Scrushy, founder of Birmingham-based HealthSouth Corp., was convicted along with former Governor Don Siegelman, a Democrat, of bribery, conspiracy and fraud in an alleged quid-pro-quo scheme involving trading campaign contributions for political favors. Those convictions are being appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The Langford case and the county’s handling of its finances have deepened local cynicism.

‘Start Over’

“I think they need to clean the whole thing out and just start over,” says Kim Jackson, a county elementary-school teacher from the town of Hoover.

Sitting on a bench in downtown Kelly Ingram Park, a scene of civil-rights struggles in the 1960s, Andrew Lewis, a part- time laborer who sometimes leads informal park tours, calls the situation “a disgrace.”

The sewer financing debacle began in 1996, when the county entered into a consent decree with the federal government to upgrade sewers that were blamed for polluting the local watershed. The estimated $1.5 billion project grew into a $3.2 billion behemoth, and in 2002 — the year Langford was elected to the commission — county leaders began refinancing about $3 billion in tax-exempt bonds that had helped pay for the improvements.

Interest rates were at a 30-year low. While that made fixed rates attractive, a JPMorgan banker advised commissioners to issue variable-rate debt with swaps layered on top to create a “synthetic fixed rate.” The technique was “supposed to provide a lower rate than traditional fixed rate” bonds, according to a letter Collins sent to the SEC in June.

Theory of the Deal

Under the deal, the county would pay JPMorgan a fixed rate in return for receiving floating-rate payments from the bank. In theory, the payments to the county would match its debt obligations, leaving its swap payments to the bank as the county’s only cost.

In 2003 and 2004, with Langford as president, the commission plunged into interest-rate swaps with JPMorgan, Bear Stearns Cos., Bank of America Corp. and Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. Over time, the county, whose fiscal 2010 operating budget is $808.6 million, entered swaps on more than $5 billion in bonds.

Langford said in 2005 that the swaps would save $214 million — an assumption based on the county and its bond insurers maintaining their credit ratings.

‘Bunch of Rubes’

“You know, I get the impression that people think a bunch of rubes in Alabama shouldn’t be smart enough to utilize these swaps,” he told Bloomberg News that year.

The county later hired financial adviser James White of Birmingham-based Porter, White & Co., who estimated that the commission’s cost for the swaps, $120.2 million, was as much as $100 million too high, based on prevailing rates.

Then, in 2007-08, credit ratings for bond insurers that backed the variable-rate bonds plummeted to junk status because of unrelated losses in mortgage-backed securities. The reduction in credit quality killed demand for the bonds they insured.

Banks were forced to buy the securities, kicking in contract provisions that accelerated to four years from 40 the county’s payment schedule on more than $800 million of the debt. The insurers’ fall also affected more than $2 billion in auction-rate securities in late 2007 as bidders’ interest evaporated.

Some of the county’s variable rates more than tripled, to as high as 10 percent. Meanwhile, the bank payments it received were decreasing. In March 2009, when JPMorgan canceled its swap agreements, a county filing said they were worth more than $650 million to the bank, which has agreed to waive termination fees under negotiations on how to restructure the county’s debt.

Federal Investigations

JPMorgan disclosed in May that the SEC is investigating the bank’s role in selling the financing structure to the county. The regulatory agency, along with the U.S. Justice Department, is also conducting a nationwide investigation into alleged bid- rigging or collusion in the sale of “municipal derivatives.”

As for Langford, he “sold out his public office to his friends Blount and LaPierre for about $235,000 in clothes, watches and cash to pay his growing personal debt,” said a Department of Justice press release that accompanied the unsealing of his indictment in December. Of more than $7 million in fees Blount allegedly received, he kicked back $371,932 to LaPierre, according to federal documents in the case.

In one instance, Langford demanded $69,000 “to influence and reward him in connection with Jefferson County financial transactions,” according to a July 29 plea agreement LaPierre filed in Birmingham federal district court. In June 2003, Blount wrote a $69,000 check to LaPierre who, three days later, wrote a $69,000 check to Langford, according to the agreement.

Upscale Clothier

Between May and November 2004, Blount and LaPierre — using checks and American Express cards — spent $12,000 on clothing and luxury goods for Langford at Remon’s Clothier, an upscale Birmingham retailer, the government alleges.

LaPierre, 59, pleaded guilty July 29 to one count of conspiracy and to filing a false tax return. Blount, 55, pleaded guilty Aug. 18 to one count of conspiracy and one count of bribery and agreed to forfeit $1 million. Blount faces as many as 10 years in prison; LaPierre five years.

Their sentences might be reduced, assuming “substantial assistance” to the government at Langford’s trial, according to their plea agreements.

Some aren’t betting against Langford.

“Well, he’s been a politician for a long time,” says Maralyn Mosley, 71, an activist in the black community. ‘I think he knows his way around the minefields.”

Sackcloth and Ashes

At least some of his popularity stems from Langford’s displays of faith in a city that has one church for every 346 people — more than twice the national average, according to figures provided by the Association of Religion Data Archives at Pennsylvania State University in University Park.

Addressing violence in city schools, the mayor in April 2008 got the city council to proclaim a “day of prayer, sackcloth and ashes.” During an event at a packed downtown auditorium, he handed out actual sackcloths — purchased, says Vance, with private money.

Framed in glass on a wall outside his office is an epistle titled, “Letter from Heaven.” It says: “Dear God, Why do you allow so much violence in our schools? Signed, a concerned student.”

“Dear Student,” the letter continues. “I’m not allowed in schools. Signed, God.”

God is often invoked around Birmingham’s marbled city hall — and not just by the mayor. At the council meeting that featured the moon-shot video, Mary Garrett, pastor of the Matthews Chapel A.M.E. Church in Fackler, Alabama, delivered a three-minute invocation.

“We continue to ask you to correct, improve, remove and repair the problems and situations we have caused, instigated, messed up or torn down,” she prayed, “for we forgot to consult you from the beginning.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Ken Wells in New York at [email protected].

Last Updated: October 19, 2009 00:01 EDT

By Ken Wells

Source: Bloomberg